|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Scrapbook:

A book, similar to a notebook or journal, in which personal or

|

||||

|

************* or anywhere else in the stream, for that matter. Hell, get off your horse and float along, see where it takes you.

************* "In for a penny, in for a pound."

************* but they have never found these dangers sufficient reason for remaining ashore." Vincent van Gogh

|

||||

I spent twenty years of my life commercial fishing the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea and all the inner waterways of Alaska, including Prince William Sound. I know the sea and love it. I've seen the ocean in all its personalities: from placid as an inland lake on a summer day, to mean and unruly as a brahma bull. I've gotten the crap kicked out of me by it, and I've stood on the back deck of some boat at night gazing at the creamy band of stars stretching across the sky, our Milky Way, our home. I've trolled salmon, worked eighteen-hour days longlining blackcod, and forced my way through unending halibut trips.

I spent twenty years of my life commercial fishing the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea and all the inner waterways of Alaska, including Prince William Sound. I know the sea and love it. I've seen the ocean in all its personalities: from placid as an inland lake on a summer day, to mean and unruly as a brahma bull. I've gotten the crap kicked out of me by it, and I've stood on the back deck of some boat at night gazing at the creamy band of stars stretching across the sky, our Milky Way, our home. I've trolled salmon, worked eighteen-hour days longlining blackcod, and forced my way through unending halibut trips.The men I knew, my fishing mates, were of a different breed than what most folks are used to. The last group -- the Moss Halibut Gang -- were off the grid in every sense. It was refreshing to deal with such people. Petty pretensions and artificial attitudes had a short lifespan. Out in the Aleutians, our main stomping ground, you seldom run into another boat, so their skills, resourcefulness, and casual self-reliance always made for a reassuring atmosphere, especially when the shit was hitting the fan. We were pirates in truth and did what we had to do in order to survive. I haven't seen them for many years now; I miss their company and I miss that life. But mostly, I miss that sense of largeness and freedom that went with the territory. The main thing I remember about that whole period of time which I try to hold onto is: You knew who you were, unblinkingly, and no one and nothing could ever ever cause you to doubt yourself. It was that clean.

*************  In 1992 my fishing partner, Brian, and I did a halibut trip by ourselves. Things didn't start off that way. We'd left Akutan, our home port in the Aleutians, and ran to Dutch Harbor one horrible night. We'd been waiting for the sea to come down but it just seemed to be getting worse; throwing caution to the wind, we went for it anyway. We first tried the Ocean side but it was too rough so we backtracked through Akun Pass to the Bering which wasn't much better. It was July 4th weekend, you see, and everybody wanted to go to Dutch to party, but we arrived too late. Because of this final straw -- we hadn't been catching much of anything -- the rest of the crew jumped ship and went back to Kodiak on the ferry.

In 1992 my fishing partner, Brian, and I did a halibut trip by ourselves. Things didn't start off that way. We'd left Akutan, our home port in the Aleutians, and ran to Dutch Harbor one horrible night. We'd been waiting for the sea to come down but it just seemed to be getting worse; throwing caution to the wind, we went for it anyway. We first tried the Ocean side but it was too rough so we backtracked through Akun Pass to the Bering which wasn't much better. It was July 4th weekend, you see, and everybody wanted to go to Dutch to party, but we arrived too late. Because of this final straw -- we hadn't been catching much of anything -- the rest of the crew jumped ship and went back to Kodiak on the ferry.

We got the gear baited, iced up the next morning and headed out. It took us twenty-four hours to get there at our top speed -- 12 knots. We decided to first try the east side of Saint George island. That side is a sheer cliff -- called officially: the High Bluffs -- with hundreds of birds nesting in it. So many we had to yell to hear ourselves talk. I tied all the gear together on deck -- ordinarily you tie skates together as you go, or rather it goes, including the buoy and anchor set-ups -- and put it out myself while Brian ran the boat at full bore.

Later on, a storm came up while we were playing chess. A heavy roll rounded the bend into our anchorage and knocked a piece over. Secure as we were, hiding behind the island, we nonetheless decided to pull anchor and move farther west around the corner, so to speak. Our chess games were important to us; we took them very seriously; it's how we kept our heads. Chess, coffee, cigarettes; it's all we needed. And some fresh halibut to eat didn't hurt either.

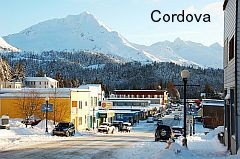

*************  From October 1990 to the following spring I lived on a 25-foot cabin skiff tied-up at the first finger of the far dock next to the breakwater of Cordova harbor. In the winter I had to occasionally shovel snow off it to keep it from sinking. In the mornings I'd go out on deck to take in the day and almost always a sea otter would be in the vicinity; we were neighbors. He was a hell of a lot tougher, which inspired me while putting things in perspective. The morning ritual included going uptown to the Alaskan Bar for coffee. Invariably at the top of the gangplank an eagle would be sitting on the rail a few feet away. We'd eyeball each other as I passed and that was that.

From October 1990 to the following spring I lived on a 25-foot cabin skiff tied-up at the first finger of the far dock next to the breakwater of Cordova harbor. In the winter I had to occasionally shovel snow off it to keep it from sinking. In the mornings I'd go out on deck to take in the day and almost always a sea otter would be in the vicinity; we were neighbors. He was a hell of a lot tougher, which inspired me while putting things in perspective. The morning ritual included going uptown to the Alaskan Bar for coffee. Invariably at the top of the gangplank an eagle would be sitting on the rail a few feet away. We'd eyeball each other as I passed and that was that.

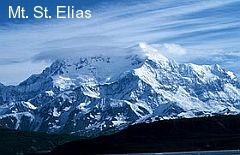

In the winter, walking up the harbor road I would be mesmerized by the distant mountains north, usually topped by smears of oily grey clouds, the combo radiating an ominous presence. Mean to the core, they silently gave testament to their rugged uniqueness, resisting easy classification. Jagged and sharp-hewed in appearance, they articulate an implacable resolve, an adamant refusal to give an inch.

A friend I worked with on the High Tides Seafood's expedition once pointed out how they seem to demand that a person go out to them. They draw you out, unlike softer-edged and eroded mountains elsewhere. He was right. Whenever I see a picture of PWS mountains -- The Chugach -- in a magazine, I recognize them instantly. I've seen pictures of the Himalayas; they're similar in morphology and character, but also unmistakably themselves.

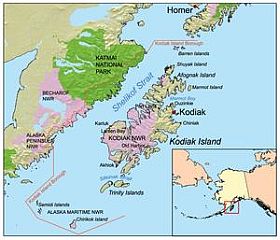

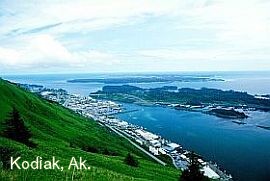

I went out on one trip with a local and made enough to fly to Kodiak, the hub of longlining and the largest fishing community in Alaska. Glouchester is, or was, its only competitor when it came to sheer production. I bought a oneway ticket; my friends saw me off at the airport. On my arrival I rented a room at the Shelikoff Lodge and then went straightaway to a bar I preferred when here two years before. Ostensibly, I was looking for work, but I still had about a thousand dollars left, so, being the way I am, there didn't seem to be any hurry to commit. I remember lying on a loading dock, half drunk, soaking up the 70 degree sun after the long winter. In those days I was totally occupied with living my life, immersed; every moment was the first and the last.

My friend, Dennis, had come here from Port Townsend for his first, and only, as it turned out, halibut trip. So through them, some time during the next few hazy days, I met the rest of the crew. They were anxious to leave so I ended up doing

As I methodically went through the gear, I watched the next show shakily try to gather steam. But the entire crew was leaving. Brian wanted to head out to Akutan, a small native village, on Akun Island in the Aleutians. Out west there's about half a dozen summer halibut openers of varying lengths. The boat, at that time, was a mess. He'd dragged it off a beach for salvage, and one whole side was corrugated in; you needed to pump the bilge every half-hour. All the windows were covered with plywood except for one narrow sliver of plastic glass in front of the hydraulic steering toggle. It was like being on the Merrimac.

The night we pulled out of Kodiak for the 800 mile trip, the kid was still attaching the running lights. The radio and radar worked but that was it; no autopilot so we had to steer by hand the whole way. Not having time to hook-up headlights, we were running blind, relying completely on the radar which was rather old and indistinct, scratchy. It gave me all the confidence of an etch-and-sketch.

It was a definite fixer-upper and that was the idea. Her outward appearance to the contrary, however, I was to learn she had the guts of a stout, tough, ocean-going vessel. But, at this time, she didn't exactly inspire confidence.

We arrived at Akun Pass late for slack tide, about one or two in the morning; it couldn't be darker for that time of year. It's an extremely narrow passage. When the tide's running, ten-foot breakers roar through, bracketing and setting the channel. That's a lot of current changing hands between the Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Akun Pass connects them; Akutan Bay is to the left if approaching from the ocean.

Brian was at the wheel, chart on his lap. Did I mention we had no headlights? The tire salesman and his son sat at

Our first trip was little more than a training exercise. I showed Brian's friend and his son how to put gear out and bring it in, etcetera. We didn't catch much. The next opener wasn't for a couple of weeks so I became familiar with the one and only bar in the village. At that time, Akutan had a population of 90; wooden boardwalks ran through the few buildings and along the beach front. The bar had two pool tables and a great jukebox, rattan ceilings and a friendly atmosphere, relaxed and down-to earth.

I stood there taking it all in, detaching my mind from everything that had gone before, right up to my present circumstances. I am here, I said quietly to myself and let my body completely identify with the surroundings, feeling the wildness and energy of the sights and sounds and play of nature's forces.

Stew and I worked well together. We could put out miles of gear without having to say a word to one another, just the occasional finger point or nod. Smooth as glass it was, working with someone who knew exactly what he was doing. Also, he volunteered to do most of the cooking. His halibut stew over Thai rice was to die for; I could eat it all day long. He would also fry up hand-size halibut cakes and pile them on a plate on the cabin table. During the course of a day, you'd grab one as you went by; they were impossible to resist and a great energy boost. I prefer fish to beef any day, but that never stopped me from devouring a mandatory cheese burger as soon as I got back to port.

What I got out of being in the Aleutians was the experience of brand new country, haphazardly rumpled and unruly country, formed by volcanoes and severe tectonic shifts. On the jagged edge of the Bering Plate, hanging over the Pacific Basin, is where the Aleutians lie -- part of the Aleutian Arc along the Ring of Fire. It's beautiful and evocative; austere and demanding. The last place, of a few remaining, where a person could truly live wild and free without feeling he was breaking some taboo. A serious no-nonsense land inspiring of other worlds and times long gone.

Imagine how tough and enormously self-reliant and courageous these people had to be, must have been. This village, and it's not the only one in the area, was built with lumber brought in by ship from who knows where, possibly the Alaskan peninsula; I don't think Kamchatka, although if they came from there, it's quite possible. All their supplies, stores of food, oil for lanterns, clothing, bedding, furniture -- everything had to be brought in and there was no sign of a dock. And this happened way before electronic communications or radio by which they could call for help or assistance. And no Coast Guard, nothing. They were totally on their own, cutoff. But maybe they liked it that way. Probably, supply ships would call on some kind of schedule, but, nonetheless, the winters are cruel and harsh and life threatening. And, except for their homes and the firewood needed for heat in a terrain devoid of trees, there's no protection from the elements.

The Community Center, which doubled as the school, had a phone which I used to call my mother in Philadelphia, just for the experience. I had trouble trying to explain where I was, but then I wasn't too sure of it myself. The few roads were dirt,

On our way down the Chain we passed a herd of reindeer resting on a beach, perhaps a hundred or more, laying on their sides, young ones strolling about. They glanced our way as we cruised by but otherwise remained aloof and completely

We were considerably closer to Kamchatka Peninsula that to mainland Alaska, a fact that tempted us. Something happens to a person when he gets far away from what's considered conventional society and enters an area consigned to the wilderness exclusively. Nobody else was out there at the time; we were completely on our own; it felt great, truly. The Aleutians -- strips you down to bedrock.

Of the four seasons we spent out there, the first was the best. Ironically, we caught more halibut and made more money when the boat was a wreck. There's a lesson to be learned by that, but I'll be damned if I know what it is.

We finally pulled out and headed up the Inside Passage, stopping briefly in Juneau to get a halibut landing permit. However, luck was not on our side. Brian had accidentally installed the new alternator with the wires crossed. So, by the time we got to Cape Spenser, 500 miles from Kodiak, our electronics went out, except for the VHF radio. By electronics I mean the old radar, the single sideband radio and the loran. GPS's were not a common feature in those days, hardly anyone had one; Loran-C was the navigation device, at least it would give your present position.

So there we were, sitting at the edge of the Gulf, debating whether to go for it or not. All we had, besides the VHF, was a

bubble compass. We were still steering by hydraulic toggle and still had no headlights. I insisted we go, what choice did we have? The rest of the crew were busy in Kodiak baiting all the gear Brian had left there. They were expecting us and

Our second day out we found ourselves in the middle of the Gulf, we believed, just going by approximate speed and general direction. The day was clear and far off to the north we spotted a cruise ship. Brian got on the radio and requested

As it stood we could've landed anywhere from Seward to the south end of Kodiak island. At the end of the third day we spotted land, and an opening, a channel. By sheer guess, Brian, unsure of exactly where we were, headed into it. We subsequently came across another fishing boat and requested position. As it turned out, fortunately, Marmot island was directly to our south, which is just above the channel leading to Kodiak. Pure luck, nothing more. Even though Brian had lived in the area for twenty odd years, our angle confused him.

For Brian and me, it amounted to a voyage of about 2,000 miles of running, running, running, from Port Angeles to Akutan. It was a mad rush from start to finish, but, par for the course in those days.

Formerly, we used to spend a lot of hours on top of the cabin, on the bow and partway up the mast scouting for orange buoys bobbing and occasionally hiding just below the surface. With the GPS, however, we almost ran over them; in fact, I did the first time, not expecting it to be that sure. We could also plot waypoints from one position to the next which the auto-pilot would dutifully follow, steering the boat to each precise location. Compared to the boat's condition in the beginning, it was like running the starship Enterprise. Another genuine miracle, to be sure.

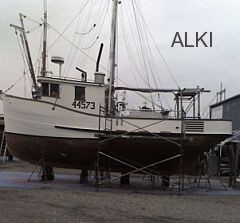

I remember one time running a boat called the Alki heading for College Fjord and having a humpback whale come out of the water and dive, tail at full sail, right in front of us. It was a magical place, and I traveled everywhere in it. The whales were amongst the first residents to move out after the spill. The news spread quickly, shocking everyone as it spelled the end to the fishing season. The Sound was a haven for all manner of marine wildlife. Birds of all kinds and sea otters, mainly, suffered from the first. The beaches were fouled and the heavy sludge not only sank to the bottom, ruining the bottom fishery and ground habitat, but also remained suspended in the water column. It didn't take long for the town to fill up with outsiders, seemingly from all over the world.

I arrived at night on the ferry from Cordova, hitched a ride in the back of a pick-up from the ferry dock to the harbor, and had no trouble spotting the Alki through the huge picture window at a harborside bar, a proper place to land in a strange town. A habit I developed more and more as years went by. Although it was night, it was also the end of June and so I had my first experience of light at night. I could see perfectly well as though it was the middle of the day.

The trick with the Delta was this: No charts existed for it at the time. Kindly donated by a local fisherman, what we had were rough pencil drawings of the approximate locations of the underwater sand bars. They shifted with the currents so there was little use in trying to fix their positions with a legitimate chart. The bars carved channels into the Delta proper from the ocean. What we had to do was determine these channels by sight, by reading the water, how it moved. Our first time out there went well, surprisingly to all concerned. We ran together, so between the lot of us we'd figured it out, mainly by watching gillnetters coming and going.

But the second time, Donovan, the skipper, and I started late for one reason or another. By the time we arrived on the ocean out front, Mary Catherine was already in place. The sea was not happy that day, choppy and turbulent, coming

Actually, we'd made two mistakes: We should've contacted the Mary Catherine first, but, we underestimated the dangers of the Delta. Lessons to be learned about that neighborhood. In fact, the keynote was the steep learning curve everyone was going through, and this was just the beginning of ours. Rule of thumb: If you're the least bit uncertain about what to do or where to go on the water, contact a running partner or make a general radio announcement, giving your location and asking for assistance. One time in Columbia Bay a crewman got seriously ill suddenly and we requested help. In minutes, half a dozen boats appeared out of nowhere. It's how it is on the water. Inside we were confronted by the beach not fifty yards away. We found ourselves in the middle of a small puddle, horseshoed by sand. As it happened, the flat spot had been an illusion caused by the very momentary dampening of wavefronts, peaks and troughs cancelling one another. That flat spot was now a series of ten-foot waves [my perspective] crashing towards the beach, with us in the middle. We had to get out, back on the ocean.

The Alki was built solid, like a giant oak log, and had more heart than one would expect from its size. Donavan held it steady, straight ahead, no broaching allowed. After a couple of seconds, she crashed -- oozed would be a better word -- through and we were out, out on the unpleasant sea. We then called the Catherine who informed us we were about two miles west of their position. Eventually, we got in safely and tied up. We told our story and everybody laughed, not derisively but that way of wild men who were very much aware of our general naivete concerning the lay of the sea. And their joking, of course, was not intended to embarrass us but to dispel whatever residual tension we may've been still feeling. They nodded and shrugged, knowing that more such experiences were apt to befall us all as we learned our way around the neighborhood.

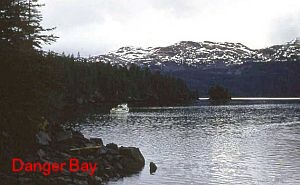

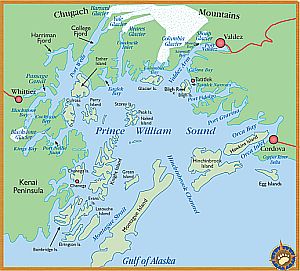

When we finally got into buying in the Sound, everyone was continuously awed and astounded by its beauty and size. I can't think of grand enough adjectives to adequately describe it or encompass the overwhelming character of its presence. Every point of view showed another facet, a different world. You could put twenty Puget Sounds inside Prince William, it's that humongous.

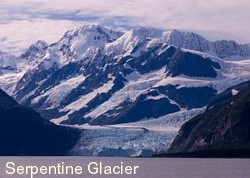

[click picture to see larger version]  We tested our eyesight with regard to telling distances. Looking off to the far mountains in the west, I guessed it to be ten miles away. But the radar told us it was twenty. Accordingly, we had to adjust our sense of space in this wide country. It's probably due to the higher latitude -- the closer you get to the North Pole, the more the Earth flattens out, increasing the distance to the horizon. But, that's not all of it. Everything -- mountains, waterways, Fjords -- seemed to be on a larger scale than in the lower forty-eight. Add to that, drifting icebergs off the many glaciers of College Fjord and the Columbia Glacier, and you have the makings for being overwhelmed.

We tested our eyesight with regard to telling distances. Looking off to the far mountains in the west, I guessed it to be ten miles away. But the radar told us it was twenty. Accordingly, we had to adjust our sense of space in this wide country. It's probably due to the higher latitude -- the closer you get to the North Pole, the more the Earth flattens out, increasing the distance to the horizon. But, that's not all of it. Everything -- mountains, waterways, Fjords -- seemed to be on a larger scale than in the lower forty-eight. Add to that, drifting icebergs off the many glaciers of College Fjord and the Columbia Glacier, and you have the makings for being overwhelmed.

When in the western part of PWS, several times we had recourse to tie-up at Whittier. Thirst drove us, mainly.

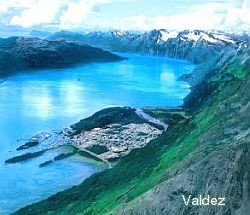

Coming out of Valdez, you pass through narrow Valdez Arm to enter the expanse of the Sound. Just beyond, off to the right, you pass Columbia Bay and its resident glacier. Back then, almost thirty years ago, its face wasn't very far into the Bay; we traveled through it a number of times for the experience. Now, I'm sure it's shrunk quite a bit. But back then, we had to be aware of the tides when coming and going. An ebb tide brought icebergs out onto the Sound directly in our path, some much larger than our boats. It would be nice to leave Valdez just as the tide is changing so as to not only run with it but also to get a maximum clear highway. Unfortunately, given the constraints of time, that's not always possible; when an opener is called for, you have to go, and sometimes that means now, regardless of the tide.

I recall one night -- later on in the season when the nights were actually dark -- I was at the wheel coming out of the Arm. The radar picked up multiple bergs in the way. I spotted another boat in the distance and no sooner had I that it

One thing, though, that we damn well had nailed down from the start was the exact whereabouts of Bligh Reef, a definite no-go zone.

So, getting back to the Exxon Valdez; what happened to it? Coming out of the Arm the Sound expands rapidly, there's plenty of room to maneuver. How they managed to run aground on the reef is up to conjecture. Everybody was

Disgusted, I decided , at first, not to take part in the mess, and instead joined a minimal crew on an 80-foot power-scowl heading for Togiak to go herring tendering. Togiak is in the northwestern part of Bristol Bay, itself in the eastern arm of the Bering Sea. The crew had jumped ship for the bigger bucks and safer duty the oil spill provided. Never one to pass up an opportunity for adventure during that period in my life, I went for it.

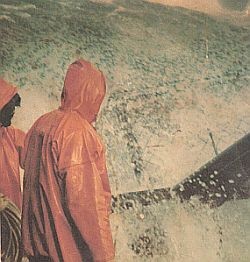

Later on, when we finally returned to Cordova, I too jumped ship -- wasn't making much and the skipper was a drunken asshole -- and got into the spill. I helped a guy run a small boat tendering a skimmer in the southwest of the Sound, near Latouche Island and Kings Passage. It was crazy, truly. Never had I seen so much money get burned up and wasted, all for the media. I remember an Exxon rep coming around telling people to look busy even if they had to make it up because a crew from Channel-5 from Seattle was coming that day. It was disgusting and degrading. Even though I was making several hundred a day doing practically nothing, I finally quit after only a month. Our job included, for the most part, tying up to the Cape Douglas, a 120-foot power scow that was being used as a holding tank for the sludge, and watch movies with the skipper. The Great Clean-Up -- the only thing that got laundered was the money that went into it.

*************  In 1987 and '88 I fished on the Lady Simpson, a 90-foot power scow. I was the deckboss the second year. A deckboss is like a foreman, only Kodiak style. We fished out of Kenai, located on the Kenai river. I flew there from Cordova on Saint Patrick's Day; the boat was already there, tied-up behind the cannery. It was break-up time on the river and in the town. I met the rest of the crew in a bar. They had a bus that took people from bar to bar all day. At one point, we all

got in, the whole bar as if on cue, filling it up practically, then the driver pulled out, made a quick U-turn and parked in front of the bar across the street. It was that crazy, but typically Alaskan.

In 1987 and '88 I fished on the Lady Simpson, a 90-foot power scow. I was the deckboss the second year. A deckboss is like a foreman, only Kodiak style. We fished out of Kenai, located on the Kenai river. I flew there from Cordova on Saint Patrick's Day; the boat was already there, tied-up behind the cannery. It was break-up time on the river and in the town. I met the rest of the crew in a bar. They had a bus that took people from bar to bar all day. At one point, we all

got in, the whole bar as if on cue, filling it up practically, then the driver pulled out, made a quick U-turn and parked in front of the bar across the street. It was that crazy, but typically Alaskan.

We got ready and we also spent a lot of time onshore. My favorite haunt was Kenai Joes. Situated on a bluff above the river, it had sawdust on the floor, pool tables and a great jukebox. My drink of choice in those days was Wild Turkey and coke on the rocks.

Midnight of the 31st we were on the ocean near Seal Rocks, miles below the opening to Prince William Sound. The ground line was in tubs that, with bait and ice, weighed about 40 pounds each. It went out over a metal chute strapped securely to the

First the buoy and its line, then an anchor, then the gear, followed by an anchor and buoy-line, symmetric-like. The anchors weighed 50 pounds. I don't recall exactly how many strings we put out, but each string was ten tubs, and each tub was a full-skate long, 150 hooks using 18-inch gangions each separated by two-thirds of a fathom for blackcod [for halibut you use much longer gangions, or leaders. Where tied to the groundline, any pair are separated by more than the distance between their combined lengths, for the obvious reason].

While the gear soaked we busied ourselves baiting up more -- it never ends. We used fresh herring. It was the first day; none of us had worked together before and so our efforts went towards establishing an efficient routine. We'd put the gear out without a hitch, but the hard part was to come -- pulling it back in. I won't go into the gory details of our set-up

We ran an RSW system -- Recycled Sea Water -- which kept the fish below 32 degrees fahrenheit without freezing them. When pulling gear you're always sideways in the trough so the boat rocks side to side. On a deck that's usually wet from rocking [water comes through the scuppers], you use that motion to move things -- like an almost full tote of fish. You might need to move one several times during a pull -- if you're lucky -- in order to put a fresh empty in its place at the bottom of the slide. One man can push a tub containing hundreds of pounds by going with the roll. Trying to do otherwise is hopeless and demonstrates to all that you are not only a greenhorn but are also out of touch with your surroundings -- the sea.

At 6:00 AM we were on deck, on site and doing things. No wandering around sipping coffee and smoking a cigarette trying to wake up. Nope. We worked from six to midnight, every day. Ran into Kenai on friday night, delivered, cleaned the boat up -- what hadn't been cleaned on the way in -- and crashed heavily. The weekends were dedicated to repairing gear and whatever else needed doing -- groceries, making weights out of chain, going to the marine store to get new hooks or gaffs or whatever. But, saturday and sunday felt like days off, only twelve hours of work each; then, it was to the bars.

I checked the radar then turned to go down the steps to the galley for more coffee. Behind me on the wall were the trouble lights, several of them. Those alarms were turned off at night but the red lights were still active. I glanced at the board as I went by and one was blinking -- the light for the forward bilge pump. I woke the engineer to have him check while I went back to the bridge. It was about 50 feet of deck from there to the forecastle, so he took a sleepy few seconds to get there. But no sooner had he stepped across the threshold to the forward compartment, he came running back and up the steps to wake the skipper. The forward compartment was flooded and filling fast.

Despite being in good shape by this time in the season -- coiling hundreds of fathoms of buoy line per set, if nothing else, will do that for you -- we nonetheless could only do a few at a time. Five gallons of water hoisted as far over your head as you can reach as fast as you can wears you out in a hurry, especially when you're exhausted to begin with. An empty would be dropped down as you did this.

Despite our efforts, as fast as the four of us were going, we could see we were losing the battle. We needed a pump, quickly. The engineer, Stryder [that name fit him], had an interesting history and was my stateroom mate. He'd been in the CIA during the

We headed northwest to Pigot Bay which has a shallow slope to the beach. Not all power scows are flat-bottomed, some have a bit of a keel, but not too deep; they're built to carry wight. The Lady Simpson, however, is flat-bottomed, fortunately, so we ran up onto the beach a little ways, not too much; we didn't want to get stuck at low tide. The engineer was also a diver and had his gear with him. He dove down and replaced the fitting. Afterwards we ate and rested a bit while the skipper ran back to our gear on the grounds; we picked-up where we'd left off, literally, with little sleep and adrenaline in short supply. So it went. During those two years on the Lady Simpson, we also visited Seward (for repairs), Homer (for R&R) and Kodiak (closest at the time). I spent quality hours of my life in every bar in those cities; it was all part of the tour.

*************  For three years -- 1977 to '80 -- I salmon trolled off the Washington and Oregon coasts. My very first fishing expedition was on a 40-foot double-ender built in 1929 called the Falcon. We would go out to the edge of the shelf -- or the

prarie as it was called -- and fish back towards the beach, or, work laterally parallel to the beach on a particular tack-line, at a certain depth, that seemed to be where they were schooling up. Trolling is a gentleman's game.

Each fish is handled with care, cleaned and iced as quickly as possible. I say it's a gentleman's game because there's a certain amount of art to it. The way the gear is spread, the many various combinations of lures -- of which there are thousands -- and the general attitude that goes into it.

For three years -- 1977 to '80 -- I salmon trolled off the Washington and Oregon coasts. My very first fishing expedition was on a 40-foot double-ender built in 1929 called the Falcon. We would go out to the edge of the shelf -- or the

prarie as it was called -- and fish back towards the beach, or, work laterally parallel to the beach on a particular tack-line, at a certain depth, that seemed to be where they were schooling up. Trolling is a gentleman's game.

Each fish is handled with care, cleaned and iced as quickly as possible. I say it's a gentleman's game because there's a certain amount of art to it. The way the gear is spread, the many various combinations of lures -- of which there are thousands -- and the general attitude that goes into it.

The third year I fished on the

Sometimes we'd go into Westport or Neah Bay, but our home port was La Push. In those days we had long seasons so if most of the members of our group -- the Freak Fleet -- were in port at the same time, invariably there'd be a beach party, a huge bonfire of driftwood with plenty of drinking and herb. Or, we'd drive into Forks to do laundry and buy liquor and beer, sometimes champaigne to celebrate an especially good trip. Life was good but it was destined to end.

In '80 I fished on the Nomad II with Dave Goodenau, a tuna fisherman, mainly. We spent a few weeks coming out of Newport. It was a terrific boat, a 47-foot Skookum hull, a sailboat. We were in a lot of heavy seas that would've forced the Alki to head for port, but the Nomad II had little problem.

After this I went up to Alaska in '82, but not for fishing. A good friend was going to do a concrete job in Juneau, outside of town past the airport, building support walls for an office building. I went along as the labor pool. It was hard work but I loved being there. We had a house on the other side of Gastineau Channel on the beach. I was making a thousand bucks a week. When the job ended, Donavan, my old trolling partner, asked me to come to Valdez to help him with the High Tides Seafood affair. I lied and told him I was still working and how much money I was making, so he offered me an extra penny a pound. That was enough.

I flew to Prince William Sound and fell in love with Alaska. Still am.

*************

Fortunately, the deck was covered by a sturdy metal enclosure. It not only made for a safer working space, but also kept us out of the rain, which never let up. The trip lasted six days all together, if I recollect correctly, and three days of that were spent traveling to and from the grounds.

Many a time we had to jog next to our gear-buoy not thirty feet away waiting for a window of relative calm before attempting to pull it.

Living here now, near Port Townsend, I have access to the water. Occasionally I'll drive out to a point, sometimes sit on a beach log, and reminisce over the Strait of Juan de Fuca. It's not the same, of course, but it helps; the sound of the waves lapping over and over again. I'll close my eyes and remember how it all felt, a shadow of it anyway, and the people I knew and shared a lifetime with, my mates.

I have lots of Alaska stories and not all are about fishing. Two in particular come to mind. They're exemplary of the kind of people who lived there then, friendly, easy-going people. I don't know about now; in fact, it seemed to be changing for the worse even as I left. I'm not sure what causes that. People get squeezed; the adventure goes out of life. I don't know.

Another time -- you'll love this -- I needed to get away for a couple of days, three days, actually, as it turned out. The skipper had gone to Anchorage to deal with his crazy wife. I was pissed. Right in the middle of the best blackcod season in ten years and this jerk decides to go fight with his wife. As we were all ready to go fishing -- nothing needed to be done -- the rest of the crew asked me what they should do. I told them I didn't care what they did, I was leaving.

The bar was about two-thirds full; people were playing pool and the jukebox was roaring along, when suddenly, everybody in the bar walked out the side door leading to the alley/driveway. Alone, I asked the barmaid what the hell was going on. She smiled and said simply, "You better get out there," nodding towards the door. Hesitant but nonetheless supremely curious I did as she suggested.

At the doorway, I first looked down to the street-end -- no one -- then up towards the backyard. There they were, the whole bar, standing around in little groups, moving and mingling, smoking pot, which, in those days, was legal in Alaska.

That was Homer in the late 80's, one of the friendliest cities in Alaska. I spent a few months there later that year, in the fall, staying at a friend's house. I'd say it was Alaska's art colony, most of whom fished. In an atmosphere like Alaska, social circumstances are trumped by the physical, allowing your personality to grow, but not smoothly. Personalities grow bumps and protrusions -- eccentricities, I believe they're called -- because it's necessary to be as real as you can be. It's the natural state of humankind, I'm convinced, once given the room and the primitive demands of your environment. Extensions show themselves in disproportionate amounts. It compares to Cordova.

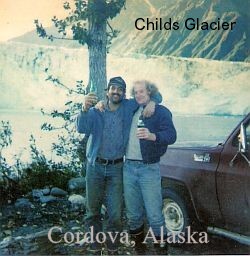

Homer was then bohemian-free-spirit fishermen, and Cordova was more working-class-roughneck fishermen. Homer is much larger, spread out and flat with an access road to the interior through Kenai and Anchorage, whereas Cordova is extremely hilly, like Juneau, and at the end of its only road out of town you'll find the Copper River, Child's Glacier and the Million Dollar bridge, from which you can drop large rocks on passing icebergs -- somethin' to do in the spring.

In the summer, we'd go out to the glacier area and camp-out for a few days, bringing all we needed: sleeping bags, firewood for camp fires, some food -- not much -- and plenty to drink. We'd also take weapons: a rifle and my favorite -- a 12-gauge short-barrel pump. I'd fire it at the glacier across the river over and over at the same spot using slugs and eventually it would calve, magnificently. I imagined I caused it, but, I was pretty stoned most of the time out there, so, who knows.

So, it's about even, Homer and Cordova each have their advantages and disadvantages. They're sister cities, as is Kodiak, in fact. If you're a Cordova fisherman, you can cash a check in Kodiak, could then anyway -- the brotherhood runs deep.

I remember once, coming back from Atka, Brian and Ronny were attempting to replace a hydraulic set-up on deck, right outside the cabin door. We were heading into a confused sea of a three- to five-foot chop coming from several directions at once. The boat was being steered by a greenhorn, name of Hub who was kind of along for the ride, and thrashing all over the place when Brian came in and asked me to take the wheel.

You'd be surprised how many experienced seamen don't understand that the water is not moving, except to oscillate, it's the wave that's moving. A cork bobbing in the open sea will make a complete circle due to the wave action passing underneath. So, what's happening up there is pretty much going to be happening when you get there, so set-up for it, like a surfer. It was a skill, I suppose you'd call it, that came to me early on.

I've been up and down the Inside Passage several times; worked Lynn Canal -- Haines and Skagway; stopped at Pelican a couple of times, and I've traveled all the waterways between Cape Spencer and Dutch Harbor. But the ocean holds a special place in my heart. I'll always love it.

Oftentimes, when at sea, I've felt a kinship with the brotherhood, an eight thousand year old brotherhood, coursing through my veins. And I've sensed the aliveness of the sea. I'm not referring to the creatures that live in it; I mean the ocean itself. It has that presence.

I'm old now and it's unlikely I'll ever be on it again. But, some nights, with the help of a bottle of wine, I can revisit times, places, events and the men and women I've known with whom I shared incredible experiences at sea. We risked our lives together; that's not something to be taken lightly.

May they live long and prosper. At least, may they never forget.

*************

I don't anymore and haven't for some time. Screw 'em. I take people at face value. Nobody grows up entirely unscathed. Everybody has dysfunctional problems to deal with and get over. Understanding for children, yes, but after a certain age, that's it.

If someone decides, for whatever reason, rational or irrational, to crap all over my life and what I care about, to attempt to ruin and spoil my joy of it for no better reason than jealousy or simply because it gives that person pleasure to do so, then the hell with him.

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

Bio

I was born and raised in West Philadelphia. [Pictures of my old neighborhood--fifty-five years ago--can be found through here.] It's one of those cities in America where you only have to give its name and not the state, like L.A. or New York or Boston. My neighborhood was one of red-brick row houses with coal heat; my street: North Sickles street laid between 54th and 55th, on the east and west, Poplar street on the south side and Girard avenue to the north, a main street of cobblestones, not great for bicycles. Two sets of trolley tracks ran down the center that could take you to 52nd street where you could catch a bus to Market street where the el/subway ran. This takes you downtown to the financial district where my mother worked.

I was born and raised in West Philadelphia. [Pictures of my old neighborhood--fifty-five years ago--can be found through here.] It's one of those cities in America where you only have to give its name and not the state, like L.A. or New York or Boston. My neighborhood was one of red-brick row houses with coal heat; my street: North Sickles street laid between 54th and 55th, on the east and west, Poplar street on the south side and Girard avenue to the north, a main street of cobblestones, not great for bicycles. Two sets of trolley tracks ran down the center that could take you to 52nd street where you could catch a bus to Market street where the el/subway ran. This takes you downtown to the financial district where my mother worked. The neighborhood was about half black and half white of which were mostly Irish and German. Two other side streets to the east, Conestoga and Yewdell, had corner grocery stores. We didn't have front yards -- there was just the street -- and the backyards were tiny, ours big enough for my grandmother to hang wash.

My grandmother made the best iced tea I've ever tasted. We were in and out of the house all night, the screen door

In the winter we had monstrous snowfalls back then -- in the 50's -- blizzards. We'd walk through drifts on our way to school -- Our Lady of Victory at 54th and Vine -- our galoshes covered when we got there. I recall the sound of the radiators steaming and the smell of the rubber snow-gear drying in the long closets at the back of the classroom. Not much in the way of synthetics in those days.

Around the date of the Epiphany -- January 6th -- a strange ritual would take place. At the bottom of our street was a vast dirt lot, it was called the Mill lot. For a week or so prior to the DAY, people would gather Christmas trees, dry Christams trees and stack them in a massive pile on the Mill lot, hundreds of trees. Then, on the night of January 6th, the whole neighborhood would surround it and set it on fire. I'll never forget the sound of dry Christmas trees burning, the heat and smell, the intense flames roaring, watching the adults, drinking and laughing, the sight of their faces in the light of the flames, me, a child less than ten years old. Talk about a pagan ritual. The cops never showed up that I remember.

When we moved away, I was 12, I waved to my friends sitting on the front steps of my house, smiling. I was too young to realize what it meant, moving out from the place where I grew up. Nothing afterwards could even begin to compare to my experiences there. Different worlds entirely.

My neighborhood. It's funny, now, at the age of 60, I find myself thinking about it from time to time. Images pop into my head while doing the strangest things. There was something about it that I now also feel, I don't know. I recall playing in

I feel like I've gone full circle, back to the beginning with my feelings and thoughts and imaginings. For that reason, I feel like I don't have much longer to live. But it doesn't worry me, really. I walked away from the Catholic Church when I was a teenager. I had problems, fears, and my religion proved to be of little help in assuaging them. So, I quit. I don't believe in heaven and hell or an afterlife. But, if it does turn out that after we die we reunite with those we love and with whom we've shared incredible experiences, it would be wonderful. If only it were true.

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

*****************************

*****************************

|

||||

So Brian and I returned to Akutan and because of serious lack of funds -- we couldn't afford the fuel to return to Kodiak -- decided to go on a trip by ourselves. There was an opener out at the Pribilofs, so we went, had to. Our boat was a fifty-eight foot steel, deep-draft like a troller hull, extremely seaworthy. I know because we'd been in many a bad weather situation with it and it performed admirably.

So Brian and I returned to Akutan and because of serious lack of funds -- we couldn't afford the fuel to return to Kodiak -- decided to go on a trip by ourselves. There was an opener out at the Pribilofs, so we went, had to. Our boat was a fifty-eight foot steel, deep-draft like a troller hull, extremely seaworthy. I know because we'd been in many a bad weather situation with it and it performed admirably. Unfortunately, we caught next to nothing by way of halibut, mostly Irish Lords, a general category, small fish that come in many combinations of colors, which we threw back still fluttering. We then moved farther out into deeper water and had better luck, but not great, 2,000 pounds was about it. We anchored on the north end of Saint Paul island -- the other island -- there's only two main ones. While I was on the back deck cleaning fish, a large fur seal shot up out of the water to port. I'll never forget it, not having ever seen one face to face before, or since. He looked at me and I, him. As he checked me out I couldn't help but be impressed by the intelligence and inquisitiveness of his eyes, much moreso than your ordinary harbor seal. He was only about 20 feet away, out of the water at chest height. After about ten seconds, galoop, down he went.

Unfortunately, we caught next to nothing by way of halibut, mostly Irish Lords, a general category, small fish that come in many combinations of colors, which we threw back still fluttering. We then moved farther out into deeper water and had better luck, but not great, 2,000 pounds was about it. We anchored on the north end of Saint Paul island -- the other island -- there's only two main ones. While I was on the back deck cleaning fish, a large fur seal shot up out of the water to port. I'll never forget it, not having ever seen one face to face before, or since. He looked at me and I, him. As he checked me out I couldn't help but be impressed by the intelligence and inquisitiveness of his eyes, much moreso than your ordinary harbor seal. He was only about 20 feet away, out of the water at chest height. After about ten seconds, galoop, down he went.  The trip back to Akutan held an incredible surprise. We had great weather and I was writing in my journal with Brian at the wheel. Sounding mysterious, he called me to the bridge. The sea was calm and as far as we could see in every direction were birds sitting on the water. All kinds of sea birds -- albatross, ordinary brown sea ducks, puffins -- all grouped together just sitting, being quiet. They made no sounds as we passed through them. This went on for close to an hour. As far north and south as we could see were birds off to the horizon. We estimated there must have been about ten miles of them. Being out of contact with the rest of the world, we had the erie feeling that something major had happened -- a nulcear war or some such -- that'd caused them to roost here. It was an amazing sight I'll never forget, and still I've not come across any plausible explanation. Maybe it's something that goes on all the time, I don't know. But, from having been in places not many people get to experience, I'm convinced natural events happen all over the world that remain undocumented and inexplicable. And I've been lucky enough to have seen a few.

The trip back to Akutan held an incredible surprise. We had great weather and I was writing in my journal with Brian at the wheel. Sounding mysterious, he called me to the bridge. The sea was calm and as far as we could see in every direction were birds sitting on the water. All kinds of sea birds -- albatross, ordinary brown sea ducks, puffins -- all grouped together just sitting, being quiet. They made no sounds as we passed through them. This went on for close to an hour. As far north and south as we could see were birds off to the horizon. We estimated there must have been about ten miles of them. Being out of contact with the rest of the world, we had the erie feeling that something major had happened -- a nulcear war or some such -- that'd caused them to roost here. It was an amazing sight I'll never forget, and still I've not come across any plausible explanation. Maybe it's something that goes on all the time, I don't know. But, from having been in places not many people get to experience, I'm convinced natural events happen all over the world that remain undocumented and inexplicable. And I've been lucky enough to have seen a few.  Lots of eagles come into town in the winter looking for scraps from the few restaurants. One in particular -- the Reluctant Fisherman -- situated at the dockfront was told by Fish and Game not to throw left-overs out back, which the eagles and gulls had a fancy for. The head cook countered by putting up a sign which read: Eagles not allowed to eat here. Alaska humor. I could see the tall fir tree behind the restaurant through the side window of the Club Bar up the hill on Main street. One winter day I counted 15 eagles roosting in it, ostensibly waiting for lunch.

Lots of eagles come into town in the winter looking for scraps from the few restaurants. One in particular -- the Reluctant Fisherman -- situated at the dockfront was told by Fish and Game not to throw left-overs out back, which the eagles and gulls had a fancy for. The head cook countered by putting up a sign which read: Eagles not allowed to eat here. Alaska humor. I could see the tall fir tree behind the restaurant through the side window of the Club Bar up the hill on Main street. One winter day I counted 15 eagles roosting in it, ostensibly waiting for lunch. I made myself see their raw beauty. It's not a pleasant, warm, sensual beauty, to be sure, much too dramatic for that. Instead, it grabs you, digging deeply into your emotions. Words like elegant and refined don't come to mind when trying to describe them. Personified, they'd be more like a gang of rowdies likely to break up a bar on a saturday night.

I made myself see their raw beauty. It's not a pleasant, warm, sensual beauty, to be sure, much too dramatic for that. Instead, it grabs you, digging deeply into your emotions. Words like elegant and refined don't come to mind when trying to describe them. Personified, they'd be more like a gang of rowdies likely to break up a bar on a saturday night. Unloading trailers for the only supermarket in town was my main money source; it got me by. Most everyone else was in the same straits -- getting through the winter, waiting for longline season. I scribbled a mantra on the ceiling above my bunk to guide me: Get it up on step. I intended to make as much money as posssible that fishing season. It finally came.

Unloading trailers for the only supermarket in town was my main money source; it got me by. Most everyone else was in the same straits -- getting through the winter, waiting for longline season. I scribbled a mantra on the ceiling above my bunk to guide me: Get it up on step. I intended to make as much money as posssible that fishing season. It finally came. A couple of days later I was walking across the main intersection downtown heading for a bar when I heard someone call my name from a passing car. I turned around wondering who knew me in Kodiak and did I owe this person any money. Surprise, surprise, it was a good friend from Port Townsend, Washington; he was with an old friend of his -- Mike, aka: Bullhead -- who I didn't know at the time. The Kodiak King Crab festival was in full swing and the weather was warm, clear and balmy, so we grouped up and proceeded to party all over town. At one point I told my friend I'd bought a oneway ticket; I was that resigned to my fate. I'll never forget his response; he said, "Sometimes you just hafta throw your shit into the wind." That became my new mantra.

A couple of days later I was walking across the main intersection downtown heading for a bar when I heard someone call my name from a passing car. I turned around wondering who knew me in Kodiak and did I owe this person any money. Surprise, surprise, it was a good friend from Port Townsend, Washington; he was with an old friend of his -- Mike, aka: Bullhead -- who I didn't know at the time. The Kodiak King Crab festival was in full swing and the weather was warm, clear and balmy, so we grouped up and proceeded to party all over town. At one point I told my friend I'd bought a oneway ticket; I was that resigned to my fate. I'll never forget his response; he said, "Sometimes you just hafta throw your shit into the wind." That became my new mantra. their gear work, refitting the groundline. That's when I met Brian, who owned the boat, such as it was in those days. Mike had a small boat called the Helen-O where I did the work, parked over in the other harbor. Kodiak has two main harbors, the one out of town across the bridge is called Dog Harbor; why, I don't know. So, I had the small boat to myself and I could do a half-skate of gear in about a half-hour at cruise speed. I was supposed to be looking for work and here it found me. He was paying me 20 bucks each. I'd do ten in the morning and then quit for the day and head uptown to meet up with Dennis and Mike.

their gear work, refitting the groundline. That's when I met Brian, who owned the boat, such as it was in those days. Mike had a small boat called the Helen-O where I did the work, parked over in the other harbor. Kodiak has two main harbors, the one out of town across the bridge is called Dog Harbor; why, I don't know. So, I had the small boat to myself and I could do a half-skate of gear in about a half-hour at cruise speed. I was supposed to be looking for work and here it found me. He was paying me 20 bucks each. I'd do ten in the morning and then quit for the day and head uptown to meet up with Dennis and Mike. An old friend of Brian's -- a Firestone tire salesman -- and his teenage son, neither one of whom had ever been on a boat before, were Brian's crew. It didn't look too promising; in fact, I felt like I was watching a train wreck happening in slow motion. I continued to work the gear and keep to my schedule, such as it was. When I was almost finished he asked me if I'd like to go along, out west, to the Aleutian Islands, to go halibut fishing on his wreck of a boat. He just kind of sprung it on me in a casual way while he and I were driving down the road in his pick-up, like he was asking if I wanted to stop for a beer. Although I could see from the start that he could use my help, I didn't intend to volunteer. But the prospect of seeing that country genuinely intrigued me. I'd been to Togiak and Toksook Bay in '89, but this was

all new territory on a different mission. Besides, how could I refuse something so completely off the wall?

An old friend of Brian's -- a Firestone tire salesman -- and his teenage son, neither one of whom had ever been on a boat before, were Brian's crew. It didn't look too promising; in fact, I felt like I was watching a train wreck happening in slow motion. I continued to work the gear and keep to my schedule, such as it was. When I was almost finished he asked me if I'd like to go along, out west, to the Aleutian Islands, to go halibut fishing on his wreck of a boat. He just kind of sprung it on me in a casual way while he and I were driving down the road in his pick-up, like he was asking if I wanted to stop for a beer. Although I could see from the start that he could use my help, I didn't intend to volunteer. But the prospect of seeing that country genuinely intrigued me. I'd been to Togiak and Toksook Bay in '89, but this was

all new territory on a different mission. Besides, how could I refuse something so completely off the wall? Fifty-five gallon drums of diesel were strapped to the side-rails on deck from which we hand-pumped into a day-tank that gravity-fed the engine. The boat was rusted and in desperate need of paint. Where the caprail should've been was a wavy edge of sharp steel. I was to find out later that the anchor winch didn't work. Setting it was no problem; you just let it drop. But pulling it, it was like days of old when the men would form a chain gang to hoist it up. That's how we began our mornings in some places. It got the blood pumping.

Fifty-five gallon drums of diesel were strapped to the side-rails on deck from which we hand-pumped into a day-tank that gravity-fed the engine. The boat was rusted and in desperate need of paint. Where the caprail should've been was a wavy edge of sharp steel. I was to find out later that the anchor winch didn't work. Setting it was no problem; you just let it drop. But pulling it, it was like days of old when the men would form a chain gang to hoist it up. That's how we began our mornings in some places. It got the blood pumping. In fact, on the way, surprise, surprise, the engine crapped out as we made a turn around a heavy rocky islet, actually just a bunch of giant rocks piled on top of one another. Drifting into it the tire salesman was trying to fish the metal rod that fit into the pump out of a drum so we could fill the day-tank. It had somehow unscrewed itself and now was somehwere in there,

the only access the small round opening where the cap went. An impossibility, I thought, as we drifted closer and closer to the boulders. It was a beautiful sunny day which made the edges of things -- like large, gnarly, mean-looking rocks -- extremely vivid. Thirty yards or so from the rock pile, he miraculously fished it out, attached it to the pump and began to fill the day-tank. As we were doing that, however, the engine suddenly started up. I went inside and Brian told me the problem wasn't fuel but rather a wet filter. He was using rolls of paper towels for filters. That's how it went. I began to expect and anticipate miracles and so got very relaxed and almost cavalier about the whole affair.

In fact, on the way, surprise, surprise, the engine crapped out as we made a turn around a heavy rocky islet, actually just a bunch of giant rocks piled on top of one another. Drifting into it the tire salesman was trying to fish the metal rod that fit into the pump out of a drum so we could fill the day-tank. It had somehow unscrewed itself and now was somehwere in there,

the only access the small round opening where the cap went. An impossibility, I thought, as we drifted closer and closer to the boulders. It was a beautiful sunny day which made the edges of things -- like large, gnarly, mean-looking rocks -- extremely vivid. Thirty yards or so from the rock pile, he miraculously fished it out, attached it to the pump and began to fill the day-tank. As we were doing that, however, the engine suddenly started up. I went inside and Brian told me the problem wasn't fuel but rather a wet filter. He was using rolls of paper towels for filters. That's how it went. I began to expect and anticipate miracles and so got very relaxed and almost cavalier about the whole affair. We stopped in Sand Point to get a few things and fuel up. I got seriously drunk and that's how I left. As we untied and pulled away from the dock -- it was blowing about twenty-five knots -- the cap flew off the stove pipe into the harbor, abandoning ship. Coward, I thought, derisively.

We stopped in Sand Point to get a few things and fuel up. I got seriously drunk and that's how I left. As we untied and pulled away from the dock -- it was blowing about twenty-five knots -- the cap flew off the stove pipe into the harbor, abandoning ship. Coward, I thought, derisively. the table, heads down. I sat in the doorway, my back pushed against one jamb, one foot braced against the propane tank and the other, the opposite jamb. It was an interesting ride, to say the least. Seeing the sweat beading on Brian's face in the faint illumination of the radar screen as he studied the chart, then the radar, back and forth, never looking outside through the sliver of wet plexiglass -- why bother, couldn't see anything -- I entertained no doubts. No one could rivet his attention to a task like Brian; I saw that early on in our partnership. Forty minutes or so later, we tied up to a 100-foot hotel ship at the far end of the bay where the workers at the Trident Seafood cannery lived. We'd made it.

the table, heads down. I sat in the doorway, my back pushed against one jamb, one foot braced against the propane tank and the other, the opposite jamb. It was an interesting ride, to say the least. Seeing the sweat beading on Brian's face in the faint illumination of the radar screen as he studied the chart, then the radar, back and forth, never looking outside through the sliver of wet plexiglass -- why bother, couldn't see anything -- I entertained no doubts. No one could rivet his attention to a task like Brian; I saw that early on in our partnership. Forty minutes or so later, we tied up to a 100-foot hotel ship at the far end of the bay where the workers at the Trident Seafood cannery lived. We'd made it. I recall one sunny day, trying to recover from a hangover, I walked to the point overlooking Akun Pass. Giant boulders were strewn here and there on the far side, waves roiled through. From my position I could see both the ocean and the Bering. The cliff formations were sharp and jagged as though freshly cut. There were no trees or brush, greenery hugged the ground where it could and splotches of diehard snow showed in shadowy places. At the head of the bay the volcano smoked continuously; you could see soot on the snow near the top.

I recall one sunny day, trying to recover from a hangover, I walked to the point overlooking Akun Pass. Giant boulders were strewn here and there on the far side, waves roiled through. From my position I could see both the ocean and the Bering. The cliff formations were sharp and jagged as though freshly cut. There were no trees or brush, greenery hugged the ground where it could and splotches of diehard snow showed in shadowy places. At the head of the bay the volcano smoked continuously; you could see soot on the snow near the top. I lay down in the tall grass at the base of the hill and closed my eyes. It was silent except for the sound of rips through the Pass, battering the massive gnarled rocks, but in a rhythmic manner, peaceful like. After some time went by I heard children running all around me; one little girl called me lazybones followed by laughter from others. About ten minutes later I opened my eyes, got to my feet and looked up the steep, green hill. Against an impossible blue sky at the top of the ridge, two women and a whole gaggle of kids stood in line holding hands and facing my direction. They all looked down at me, smiled and waved. I waved back. I could hear some of the children giggling. A picture I won't forget.

I lay down in the tall grass at the base of the hill and closed my eyes. It was silent except for the sound of rips through the Pass, battering the massive gnarled rocks, but in a rhythmic manner, peaceful like. After some time went by I heard children running all around me; one little girl called me lazybones followed by laughter from others. About ten minutes later I opened my eyes, got to my feet and looked up the steep, green hill. Against an impossible blue sky at the top of the ridge, two women and a whole gaggle of kids stood in line holding hands and facing my direction. They all looked down at me, smiled and waved. I waved back. I could hear some of the children giggling. A picture I won't forget. That's another thing about Alaska in general and the Aleutians in particular. The air is so sparkling clean that the edges and textures of everything stand out crisply in vivid detail and contrast, intensifying the grandeur and severity of the natural surroundings, affecting emotions, deepening their colors and shading their tones, helping to draw you into the immediate present. It's impossible, I believe, to resist the seductive forces at work by sheer will power. And why, for God's sake, would anyone want to? After all, isn't that what Alaska, and wilderness in general, is all about? Why we choose to be in that kind of an atmosphere in the first place? It resonates with our spirits and senses, our bodies, and by so doing, allows us to actualize our physical being and identity, at least it offers that opportunity to those looking for it.

That's another thing about Alaska in general and the Aleutians in particular. The air is so sparkling clean that the edges and textures of everything stand out crisply in vivid detail and contrast, intensifying the grandeur and severity of the natural surroundings, affecting emotions, deepening their colors and shading their tones, helping to draw you into the immediate present. It's impossible, I believe, to resist the seductive forces at work by sheer will power. And why, for God's sake, would anyone want to? After all, isn't that what Alaska, and wilderness in general, is all about? Why we choose to be in that kind of an atmosphere in the first place? It resonates with our spirits and senses, our bodies, and by so doing, allows us to actualize our physical being and identity, at least it offers that opportunity to those looking for it. On our second trip we enlisted the aid of an experienced hand named Stewart [actually, he passed out in the cabin and we took off without waking him] who stayed on and came to be a good friend. He was raised in Burma and had a British accent. Thanks to his help -- he could work hard all day without a whimper -- the trip turned out to be excellent. The Coast Guard would've liked to have known about it. Too late now.

On our second trip we enlisted the aid of an experienced hand named Stewart [actually, he passed out in the cabin and we took off without waking him] who stayed on and came to be a good friend. He was raised in Burma and had a British accent. Thanks to his help -- he could work hard all day without a whimper -- the trip turned out to be excellent. The Coast Guard would've liked to have known about it. Too late now. In fact, we came across evidence of a turn-of-the-19th century [looked like late 1800's] community in our travels. Because of the protocol by which we fished, we had recourse to navigate all the back alleys into Akutan, our home port. I recall going by a long-abandoned Russian settlement on the shores of an inland island somewhere between Dutch Harbor and Akutan. All the buildings had collapsed save the tiny Church, three walls of which still stood, and the Greek Orthodox cross somehow remained fixed to its spire.

In fact, we came across evidence of a turn-of-the-19th century [looked like late 1800's] community in our travels. Because of the protocol by which we fished, we had recourse to navigate all the back alleys into Akutan, our home port. I recall going by a long-abandoned Russian settlement on the shores of an inland island somewhere between Dutch Harbor and Akutan. All the buildings had collapsed save the tiny Church, three walls of which still stood, and the Greek Orthodox cross somehow remained fixed to its spire. I spent the next four summer seasons out there with Brian. On one ill-fated trip the following year we went as far down the

Chain as about twenty miles or so passed

I spent the next four summer seasons out there with Brian. On one ill-fated trip the following year we went as far down the

Chain as about twenty miles or so passed  We had to stop at Atka to register for the area; that's how they do it. It was early morning when we rounded the corner approaching Atka Bay. The miniature bay, more like a cove, and island were shrouded in misty clouds. Although I'm not sure

what I mean by this, its appearance was exactly what one would imagine. Atka had no dock at the time, so we anchored up. Brian and I rowed to the beach. The absence of a breakwater or spit meant the bay was actually part of the Bering. The tide was heading out, or ripping by, and so it took both of us to row; he pulled on the oars, I pushed. The beach was black from volcanic sand, black and shimmery. After finding the person representing the fishery on the island in order to register for the halibut opener, we did some touristing.

We had to stop at Atka to register for the area; that's how they do it. It was early morning when we rounded the corner approaching Atka Bay. The miniature bay, more like a cove, and island were shrouded in misty clouds. Although I'm not sure

what I mean by this, its appearance was exactly what one would imagine. Atka had no dock at the time, so we anchored up. Brian and I rowed to the beach. The absence of a breakwater or spit meant the bay was actually part of the Bering. The tide was heading out, or ripping by, and so it took both of us to row; he pulled on the oars, I pushed. The beach was black from volcanic sand, black and shimmery. After finding the person representing the fishery on the island in order to register for the halibut opener, we did some touristing. and most of the buildings were government style, metal roofs, aluminum-framed windows. People drove around on those four-wheel utility vehicles, which, we were told, is what they use to hunt reindeer in the winter. Occasionaly, someone chasing a deer or herd would fall into a crevasse on the snow/ice fields. It's a dangerous pursuit but they have little choice. Hunting, fishing, trapping, that's it. I don't recall a grocery store, but there's only one in Akutan, which by comparison is a big town.

and most of the buildings were government style, metal roofs, aluminum-framed windows. People drove around on those four-wheel utility vehicles, which, we were told, is what they use to hunt reindeer in the winter. Occasionaly, someone chasing a deer or herd would fall into a crevasse on the snow/ice fields. It's a dangerous pursuit but they have little choice. Hunting, fishing, trapping, that's it. I don't recall a grocery store, but there's only one in Akutan, which by comparison is a big town. indifferent. They call Atka the birthplace of the winds, and it definitely deserves that title. We had no luck out there and didn't persist after the point where we realized that our lack of local knowledge proved to be too serious a handicap to push it. But we did see some raw desolate country, peopled by albatross. Brown, white and shades of gray are the dominant colors. Throw in a splash of green here and there spotted with clumps of wild flowers -- fireweed, lillies, lupins, goldenrod, blue iris -- and you pretty much have it.

indifferent. They call Atka the birthplace of the winds, and it definitely deserves that title. We had no luck out there and didn't persist after the point where we realized that our lack of local knowledge proved to be too serious a handicap to push it. But we did see some raw desolate country, peopled by albatross. Brown, white and shades of gray are the dominant colors. Throw in a splash of green here and there spotted with clumps of wild flowers -- fireweed, lillies, lupins, goldenrod, blue iris -- and you pretty much have it. Returning to Kodiak after that first summer, north of the Shumagin Islands where Sand Point is, we rounded a corner and the air abruptly transformed from chill, salt, damp to this aromatic, almost pungent, pleasurable smell I knew but couldn't quite place. I told Brian. He took a whiff and informed me it was the Spruce Forests of the Kodiak Archipelago. How wonderful and how taken for granted. It was good to be home.

Returning to Kodiak after that first summer, north of the Shumagin Islands where Sand Point is, we rounded a corner and the air abruptly transformed from chill, salt, damp to this aromatic, almost pungent, pleasurable smell I knew but couldn't quite place. I told Brian. He took a whiff and informed me it was the Spruce Forests of the Kodiak Archipelago. How wonderful and how taken for granted. It was good to be home. After that first season out west I'd made enough money to visit my mother and sister back east in Philadelphia. Brian had brought the boat down to Port Angeles, Washington near where his brother lived. He replaced the corrugated port side of the

boat with fresh steel and put a new engine in. The following spring, I flew back to Port Townsend and got in touch with him. The hold was being refitted with new steel, but time was running out; we needed to get up to Kodiak. So I took up

After that first season out west I'd made enough money to visit my mother and sister back east in Philadelphia. Brian had brought the boat down to Port Angeles, Washington near where his brother lived. He replaced the corrugated port side of the

boat with fresh steel and put a new engine in. The following spring, I flew back to Port Townsend and got in touch with him. The hold was being refitted with new steel, but time was running out; we needed to get up to Kodiak. So I took up

residence on the boat, high and dry in the boat parking lot, and hurried things along, pointing out to the two men working on the boat, one, a good friend of Brian's and mine from Kodiak, one of the best welders anywhere, what could be considered an emergency and what could wait. Plus, a big plus, I installed plexiglass windows where the plywood used to be.

residence on the boat, high and dry in the boat parking lot, and hurried things along, pointing out to the two men working on the boat, one, a good friend of Brian's and mine from Kodiak, one of the best welders anywhere, what could be considered an emergency and what could wait. Plus, a big plus, I installed plexiglass windows where the plywood used to be. time was fleeting. So we went for it, steering by hand the whole way. Our heading was west by southwest according to the chart. Steering at night without lights into a usually rough sea had become commonplace. Anything or anybody could suddenly appear in front of us, but, that's how it was, plain and simple.

time was fleeting. So we went for it, steering by hand the whole way. Our heading was west by southwest according to the chart. Steering at night without lights into a usually rough sea had become commonplace. Anything or anybody could suddenly appear in front of us, but, that's how it was, plain and simple. latitude and longitude. We discovered we were sixty miles farther north than we thought, but just about in the middle. We learned something that was probably common knowledge: the flood tide on the Gulf is a lot stronger than the ebb. So after that, when I was a the wheel, I headed more southerly.

latitude and longitude. We discovered we were sixty miles farther north than we thought, but just about in the middle. We learned something that was probably common knowledge: the flood tide on the Gulf is a lot stronger than the ebb. So after that, when I was a the wheel, I headed more southerly. We pulled into the harbor and contacted the crew. They were just finishing up the gear work and immediately brought it down to load up. McGyver, Leonard's nickname and deservedly so, saw that the alternator wires were backwards and fixed that,

thank goodness. Some welding needed to be done and groceries to be loaded and a few other items, but by end of day, we were heading out to Akutan.

We pulled into the harbor and contacted the crew. They were just finishing up the gear work and immediately brought it down to load up. McGyver, Leonard's nickname and deservedly so, saw that the alternator wires were backwards and fixed that,

thank goodness. Some welding needed to be done and groceries to be loaded and a few other items, but by end of day, we were heading out to Akutan. Over the following two years the boat was upgraded considerably. A GPS to replace the Loran; a new radar, thank God; and an autopilot which Brian, in his genius, networked into both the GPS and steerage, creating an integrated navigation system. The GPS helped enormously. Not only did we have a constant and instantaneous readout of position, but we used it to fish, marking events on the display when dropping buoys.

Over the following two years the boat was upgraded considerably. A GPS to replace the Loran; a new radar, thank God; and an autopilot which Brian, in his genius, networked into both the GPS and steerage, creating an integrated navigation system. The GPS helped enormously. Not only did we have a constant and instantaneous readout of position, but we used it to fish, marking events on the display when dropping buoys.

On March 24th, 1989, the oil tanker Exxon Valdez ran into Bligh Reef and disgorged millions of gallons of thick sticky crude oil. I was living in Cordova at the time getting ready for longline season the old-fashioned way. Prince William Sound, prior to the disaster, was the most beautiful expanse of water, mountains, glaciers, whales and wildlife I'd ever seen or could've imagined. It's never returned to that state.