Part I

LOST & FOUND

600 MILLION YEARS AGO: EARTH TIME

Preliminary Appraisal

Expansion terminated prior to

internal actualization of pre-set parametric profile --- factor or factors

undetermined. Vacuum patterns of underlying particle/wave generation not

equivalent to any prearranged eigenset. Prescribed unit-matrix undetected

--- communication link singular. Placement in web under defined position

operator indeterminable --- metric environment a non sequitur -- allowed localizations non-existent and/or non-definable. Resident network rejecting corporeal manifestation of this unit. To counter, this unit exerting hyperbolic pressure beyond local periphery. Interface of fundamental shapes not congruent on third and greater integral dimensions. Harmonics linearly phase-shifted --- incoherent resonance by cross-scale invariance set. Background/foreground interplay under unit's standards protocol --- separable, disconnected, asymmetric.

Systems Critical

Condition: Collapse Immanent ---

compression to infinite density at locus of spatial identity.

Reason:

Decoherence of initial-condition configuration sets --- no set isomorphic

to existent profile --- cause unknown.

Solution: Null Space

generation.

Outcome: Complete spacetime reformulation.

Option: Possible avoidance if nature of malfunction

can be ascertained and corrected.

Procedure: Must circumsphere nucleus,

compact cell, block external inflation and decompress implosion.

Physical Manifestation

Nine space vortices transformed

by quotient space reduction --- shape spherical --- self-contained

enclosures insulated from central rift --- interchange attachments

joined and reinforced.

Central aperture connected to root

dimensions enveloped --- unable to seal.

Discontinuous at

origin --- contact with incipient point rendered inaccessible ----

loop closed.

Nonlinear time components expanded --- sum

zero.

Linear time orthogonal to nonlinear plane bisecting

compacted dimensions --- coupling disengaged.

Time dimension

contracted --- zero extension.

Summary Report

Cannot effect completion towards final

state --- resident network misaligned.

Materialization ---

unqualified.

State of organics --- indeterminate due to negation of

superposed orientation.

Overall present configuration --- holographic

projection into multidimensional dual space.

Cause of factorization

error --- unknown.

Conclusion --- Action

Purpose compromised.

Interference patterns of twenty-six dimensional metric -- commensurate

with material and nonmaterial properties -- to be superimposed on the

Unformed by Creator-Force -- not possible due to malfunction. Commencing

withdrawal of core profile, in stages, from unintended material condition to

nonmaterial state to undifferentiated ethereal space --- retract -- retract -- retract.

Require assistance. Malfunction. Repeat: Require assistance --- Malfunction.

*************

Then all went black, black and cold and very, very still.

INVASION

By the middle of June, hundreds of scientists, engineers, technicians, forensics experts, journalists, clairvoyents, religious groups, interested tourists, government investigators, and kooks of all stripes and bents had poured into the little fishing town of Casgrovina. It was an overwhelming stampede. Housing was a major problem from the start, Casgrovina never having had the distinction of being listed as an ideal tourist destination. The locals were making a killing renting out, at exorbitant prices, of course, whatever had a roof, leaky or not, and four walls: storerooms, port-side warehouses, plywood shacks, and even a barn -- horses and cows let out to roam at will. Restaurants sprang up wherever they could, out on the sidewalks -- where there were sidewalks -- otherwise on one of the few roads in front of some building that had been transformed into a kitchen, in some of the posher private homes -- damn few of those -- and storage sheds -- barely standing shacks that weren't already being rented out as living quarters. Bed and Breakfasts, a hithertoo unknown phenomena, spread like wild flowers. Alcohol was served everywhere; there were no rules.The airport was expanded, facilities brought up to a rough approximation of world-class sophistication. Several new taxi 'companies' -- old personal cars that ferried people for a set fee -- roamed the small town, its growing number of bars and eateries open all night, headquarters for discussion and meetings. Activity at the port increased to fever pitch: food, fuel, machinery, scientific instruments, computers, building equipment, basic necessities [some not so necessary], flowed in. Employment for the once dying fishing village blossomed to the saturation point -- the economy was good, a boom time to be sure and, who knew how long it would last?

As with the town, the advance team headed by Doctor Yevgeny Tolstoy had long since grown, subdivided, and grown again, several times. It had been impossible for any scientist from practically any field to ignore the findings at Casgrovina, overshadowing and short-circuiting whatever else they may at that time thought important or significant -- meaning and perspective having been put on a whole new unexpected level. So, those who could dropped everything and rushed here. Because of the influx of qualified investigators, researchers and their many assistants -- engineers and computer people, in particular -- mixed groups evolved and developed over time to cover the many aspects of the project.

Recreational vehicles sprouting antennae, looking like insects at a feeding frenzy, stuffed with computers, spectrographs, magnetic imaging devices, decoders that translated atomic structure into sound and digital displays, chalkboards -- whatever was needed, new and old, took up space all over. Most new arrivals slept where they could, the younger ones dormitory style in sleeping bags on hard wood floors, or in tents spread everywhere like mushrooms. These impromptu trailer camps became the nerve centers, usually surrounded by the media and the curious, a refugee camp with the air of a university campus.

Speaking of air, sanitation had been a problem from the start until the Russian Park Service and Army Engineer Corp took over that responsibility, to everyone's appreciation. They also wanted to have eyes and ears on site; science is one thing, regardless of the magnitude of the find's significance, the Russian government is quite another. It wasn't all pollyanna-ish, in other words; there were heavies about, concerned heavies.

As it had already been accepted that the edifice, as it was loosely referred to, was off-world, the team of archaeologists and paleontologists were mostly given scant attention. Not true of the group composed largely of physicists and mathematicians; an opulently furnished three-story house on the outskirts of town, conveniently near the site, had been offered by the caretaker, astute enough to grab the once in a lifetime opportunity to make a hell of a lot more than his tiny fee. Owing to a lack of funds amongst the locals, the owner had probably picked a bad time to move her operation elsewhere. Nevertheless, it was too late, it'd been commandeered by all manner of experts in the physical sciences -- cosmology, astrophysics; particle-field, quantum, and relativity; molecular biology, genetics, paleochemistry, you name it -- all the bases were covered. The majority of reporters hung out and dozed on the front porch and makeshift sitting areas spread around the grounds like tiny fiefdoms. The main tent included the Pulitzer Prize-winning science editor from The Washington Post, Hans Glipter, himself a former university professor of quantum physics.

Glipter had a way of connecting dots that defied logic, or went around it. He also had a way with people, charismatic and personable without being phony; not your usual wooden, pocket-protector nerd. Accessible and straightforward, he was sought after by other journalists for his insights and educated guesses, but he would never reveal what he ultimately knew; that was his story, as far as he was concerned. But lately, he'd become somewhat withdrawn and secretive, introspective, a shroud occluded his usually cheery demeanor. He was troubled by what he was discovering, or not discovering; the bottom was nowhere in sight, and he wasn't sure if he wanted to go there.

Casgrovina had once been a military town as well as a fishing community -- a border town. The then Soviet Union had built an international scale airport, typically dreary Soviet Union architecture and style, to be sure, but nonetheless capable of supporting heavy jet traffic and large cargo planes. Glipter's specially equipped, 40-foot Airstream had been flown to the Casgrovina Airport only days after the May 12th news release -- the famous "Day of the Wheel from Space," now shortened to just -- "Day of the Wheel." He'd been here for almost six weeks, acclimating and familiarizing himself with the ambient space, as it were, sending weekly reports back to the POST. And although the beauty and novelty of the natural surroundings intrigued him, he was growing impatient.

After wandering the docks of downtown Casgrovina for most of the unusually sunny day -- the air was actually dry for a change -- Glipter plopped down in his leather-backed easy chair with a glass of ice, coca-cola and bourbon. He took a deep swig, then set the glass carefully on the ivory-inlaid side-table. Using his remote, he kicked in a jazz disc and leaned back slowly and heavily, coming to a stop when he got to that place, that place where his body and mind fused. He needed them both, now, to work together on this. The facts -- and the very factness of 'fact' must be brought into question -- mulled and sifted and glued and wove and permutated themselves before his eyes, organizing, integrating, dissolving, crystalizing, only to be shattered like glass with a sudden wider grasp of the situation.

Through one lens after another, gleaned osmosis-like from night-long conversations with the local science community, including colleagues from his university days, he examined the shifting picture before him. What they had to offer were details, finer magnifications on what was known, and that's all. It was not merely a black-box problem, they were working in a vacuum, and they knew it; they needed feedback, any kind, from different perspectives. They valued Glipter's, and so seemed free with knowledge and speculation. And though speculation abounded it had but one common underlying theme: it went something like this -- aliens seeding and guiding the Earth's development toward the eventual evolution of Mankind.

Always this anthropocentric, narcissistic, quasi-religious daydream -- the "Old Ones" seeding the Universe with their genes. It was irresistable, he knew, it felt so right; but, God, there has to be a larger picture? Maybe the edifice has nothing whatsoever to do with humans or evolution or life, even? Maybe the edifice is just a part that fell off a passing ship so humongously gigantic that they didn't even notice, like a hubcap?

Glipter went into the den and returned with a legal pad and pen,

stopped in the kitchinette to freshen his Wild Turkey and coke, then back to

his easychair set off near the interior-wall side of the living room. It was a warm spot, right near a heater grid; he was in to being comfortable. He wanted to collect the

facts, one more time, as he knew them. In the top left corner of the pad he

began with the roman numeral for one inscribed in a circle, a circle with

fuzz -- sine-waves of uncertainty -- and wrote:

He shoved the facts list between the cushion and the arm of the chair, and took a swig from his drink, noisily chewing a small, jagged piece of ice. They don't know much more than they did a month ago, he mused. All the talks I've had, what did I learn? Pure speculation, a rehashing of the basic facts. So many questions skirted around - later, no time right now to think about it - obvious ones, like: why no hatch or portal to enter and exit any of the spheres? Their surfaces are smooth and seamless. What of the altars or desks, or whatever, in front of each design; why are they being ignored; they don't even appear on the press releases? Did it crash-land or had it been set down deliberately? Is the number of spheres significant? Are we, am I, focused too tight on the 'edifice' itself? The designs? What's the big picture here?

A coffee-cup ring stained the yellowing newspaper article laying on the side-table. To ad nauseum he'd studied it; surely he still could have missed something; perhaps the forest for the trees. Reclining all the way, clearing his mind, jazz playing softly in the background, he proceeded to reread the article of May 12th:

|

"Discovery of Alien Craft Rocks Science" Archaeological Dig in Siberia Reveals Mystery

|

|

by Viktor Dobachevski The Associated Press |

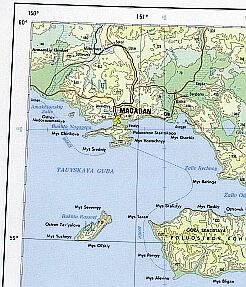

Casgrovina - East Siberia, May 12

Casgrovina - East Siberia, May 12Near the rocky coast of the Sea of Okhotsk, backed by the Kolyma Range, situated on Nagayevo Bay, fifty-eight degrees north latitude, 150 kilometers west of the port city and regional capital of Magadan, the sleepy fishing town of Casgrovina has awakened to international attention due to an accidental discovery unearthed at a construction site on the northwestern outskirts of town. A construction crew clearing rocks and generally preparing the ground for an industrial park, ran into trouble at the start of April when one of its oversized pieces of digging equipment suddenly hit something beneath the permafrost that stopped it cold. It wasn't a massive rock, at first thought, but rather, after further, more precise digging, over an area approximately 500 or so feet in a rough diagonal, with the assistance of rocket-engine sized blast heaters to melt the permafrost, an expansive network of enormous, spherically-shaped objects was exposed. What they uncovered were nine spheres arranged in a circle, equally spaced and connected to one another by enclosed, cylindrically-shaped conduits about 20 feet in diameter. Each sphere is approximately 100 feet in diameter and connected to the center sphere, itself shaped like an ellipsoid, by a conduit of the same size as that which connects them to one another, only twice as long and not curved -- do the math. The overall look is of a giant Leggo piece, or a gear from a planet-sized machine. The person in charge of the project, Vladimer Petrokoff, immediately contacted the mayor of Casgrovina who in turn contacted the Russian Ministry of the Interior. Within hours the Ministry sent a representative to inspect the site. He reported his findings by phone and, through his insistence, the Ministry informed the Russian Academy of Sciences. They, in turn, assembled and sent a preliminary team consisting of an archaeologist, a physicist, a meteorologist, two geologists, a paleontologist, and two engineers. All this happened under tight secrecy within days of the fantastic discovery. The team of experts arrived on site the following week. That was five weeks ago. Finally, a press conference was being held in the Casgrovina Community Center to announce and discuss their results so far. It was a crowded and excited scene; drawings on a large blackboard brought in for the occasion drew everyone's attention. The main figure was the design of the network itself; it looked like the schematic for a ferris wheel; on each side of it were other drawings of a more cryptic nature. The head of the team, Doctor Alexi Tolstoy, Chairman of the Archaeology Department at the University of Moscow, stood at the podium situated on a dais; behind him at floor level, seated at a long table were the other members. Doctor Tolstoy explained what they had discovered and had been able to deduce thus far. The network of spheres was several feet below the surface of the permafrost. They believe it once was above ground and had been covered over by the natural movement of rock over geologic time. This assertion brought the immediate question from the New York Times reporter: "How ancient is it?" After a long and strangely nervous pause, Doctor Tolstoy began a roundabout answer, "I would first like to introduce some of the team members: Doctors Minscheko and Petrof, our two distinguished geologists; Doctor Weingard, Nobel Laureate in Physics, now teaching at Leningrad University; and Doctor Golgachev, a renown paleohistorian, some of you may be familiar with his work in reconstructing the lifestyles of ice-age peoples. He turned briefly for whispered comments from a few of the team, then back to continue, "Doctor Weingard, in consort with our two geologists, performed what are called argon-40/argon-39 dating measurements on volcanic scrapings, zircons, from the surfaces of several of the spheres and the immediate surroundings. These tests were corroborated by a uranium series. As you may be aware," he looked quickly around the room over the top of his glasses, "there was a time when the geographic area on which we now stand was located near the equator under a shallow sea. Consequently, carbonate materials formed in the soils, a prime candidate for U-series testing. These techniques differ from the more familiar carbon-dating techniques which are only good for a range of about 60,000 years." Whispers rumbled through the group of journalists -- the area where we now stand was once at the equator? The tectonic savvy knew a bomb was about to drop. Deliberately ignoring this reaction, and concerned he may have prematurely tipped his hand, he quickly continued: "Now, this material contrasted with the surrounding rock, itself mostly the result of lava flows over millions of years. When this edifice, or whatever it is, this network of spheres, first appeared at its present location, it became encased in a crust of hardened magma. From then on it somehow managed to ride the waves, so to speak, of each subsequent flow, including, apparently, the continent-sized Siberian lava outpouring that is presumed largely responsible for the Permian-Triassic extinction of 252 million years ago, and yet retain the mineral material with which it originally made contact, under what must certainly have been considerable heat and pressure. The results are astounding; so astounding that we felt compelled to redo the measurements on many different samples using more than one element as the base." He searched the faces in the room; chin pushed up; a little perspiration showing on his brow. He couldn't stall anymore, so he forged ahead against an unseen wave, "Our conclusion, thus," he hurried, "is that the system of spheres, the edifice as we've been calling it, is 600 million years old." Doctor Tolstoy bowed his head, anticipating, no doubt, cries of disbelief. Instead what he received was stunned silence, you could hear a pin drop, as the Americans say. After regaining some semblance of composure, one incredulous-sounding word was heard from somewhere in the middle of the crowd of reporters: "What!" And then from somewhere else, "How could something so obviously sophisticated be that old; there were no humans then?" An avalanche of other related questions followed simultaneously, making them unintelligible. Motioning for calm and quiet, Doctor Tolstoy took a deep breath, then went on: "We have reasons to believe that the sphere-network was not constructed on Earth. Obviously, at that time, six hundred million years ago, as has been pointed out, there were no beings or civilization capable of building such a structure. We've examined a few of the spheres. Using magnetic and sound imaging, their surfaces prove to be seamless and continuously uniform and homogeneous, and, only one centimeter thick, difficult as they may be to believe; the nature of the material allowed for the precise determination of its thickness. Indeed, metallurgical scans have revealed that the lattice structure, or matrix, of atoms composing the material are in perfect order, minute degradation understood as possibly the result of weathering and frequency disturbances of the chemical kind. This phenomenon may be more familiar to you by way of superconductor material, metals, alloys, and ceramics, under supercold conditions, close to zero thermodynamic activity. But, to have it occur and remain uniformly consistent under the extremes of heat, pressure, and shocks, over, at the very least, 600 million years, is, quite frankly, beyond our present science to explain. "As it happens, in spite of the sheer hardness of their veneers, the spheres themselves have not proven to be impregnable, owing to this atomic orderliness. Choosing the easiest accessible, using high-powered lasers, we were able to cut a hole large enough to enter. Not being able to read the internal atmospheric composition beforehand, the possibility of an explosion was anticipated once the laser had passed through. Accordingly, we prepared and took a chance, one must do that in science from time to time. Fortunately, there were no violent reactions of any kind upon cutting through, and the gases released were captured and are presently being studied at the laboratory we've assembled on site. Samples have also been sent to the University of Moscow; we await their conclusions. I can say, however, from preliminary assessment, that they are of unknown origin; that is, you will not find them on the familiar periodic table of the elements." Continued silence followed that comment. Like children aware of being in the presence of the incomprehensible, we just sat back. One voice spoke for everyone: "What did you find, Doctor?" Doctor Weingard, the physicist, who had already been on his way, spread a few sheets of paper on the shelf of the podium and began. "We have, in fact, gained entrance to four of the spheres. Each contained a different combination of gases, none of which have we ever seen before. That is, they are not part of nor have they been produced by our planet." A fluttering of paper, then silence; we were children again, rapt listeners, waiting. Weingard continued, "Wearing protective suits, we entered the first. Our lights revealed a catacomb of smooth transparent slices of what, we don't know, a polymer perhaps, or a translucent metal, angling in all directions, floors and walls, if you will. The main floor, the one we were able to walk on, was aligned along a central axis, colinear with the conduit connecting the sphere to the center one. Off to each side were the room-like structures of varying sizes, the walls made of the same unknown material. For practical reasons, we have not as yet been able to investigate these rooms, only those parallel to the plane of the overall structure. That's another curiosity -- it's almost perfectly aligned with the gravitational field, after all that's happened geologically in the past 600 million years." Doctor Weingard walked back to the table for a drink of water, agitatedly whispered a few things to the others, then returned to the podium. "At the far end of the sphere, covering the entire curve as far as we could see, is a huge design composed of thousands, perhaps millions, of different colored shimmerings interconnected in multiple ways. 'Shimmerings' is the best I can think of to describe them; they're not lights in the conventional sense, but they possess luminosity and color. Now, because we vented these four spheres before entering, we don't know, as yet, precisely what the design, considered as the way each point connects with others, would, or should, look like. For it to represent itself true, as was originally intended, each point must remain proportional to its original frequency, that is, the colors have to vary amongst themselves in the same way. And given the quantum nature of light -- electromagnetism -- only certain wavelengths are allowed, and not others -- it is not a continuum. Also, it's possible to induce shifts in phase, either globally or locally, that will generate a completely different design. "And there are more subtle problems: Considering alien eyesight, whatever that may be, would the three-cycle of 'atmosphere -- design lights -- eyesight' play a crucial role in determining what meaning the designs may hold? So we may have lost valuable information, overcome by the excitement of the enormity and significance of this discovery, but strict scientific protocol will be maintained in the future. In order to avoid further mistakes of this kind, we need to adopt a forensic approach to the site; see in terms of 'evidence' and not so much - 'discovery-for-its-own-sake.' And so, presently we are working on methods to enter the other spheres without first venting the gases, if any, and we have no reason to suspect that there aren't." The room's quiet deepened, no one was scribbling notes or shuffling about. Pointing to a drawing on the blackboard, he went on, "Six feet in front of the design, and rising to nine feet above the floor, is a long, flat, table-like slab, having the same curvature as the sphere, eighteen feet in arc-length by three feet wide, but only one centimeter thick throughout, made of the same unknown wall and floor material, supported by a single, slender, liquid-like column or rod. Its surface is completely smooth and uniform; the same kind of atomic orderliness is evident in this material, although the class of arrangement is geometrically anti-symmetric to that of the surface material. We wait to confirm if this is the case with other surfaces of the interior, and what, of course, that may mean. Also, we could find no appearance of mechanical, electrical, or magnetic components of any kind with which we are familiar. "The other three spheres were similar except for the design on the inner wall and, of course, as stated earlier, the atmospheres varied." With that he turned to confer in earnest with his colleagues. With Weingard alongside, Doctor Tolstoy stood and approached the podium; he spoke matter-of-factly, "Scientists from around the world will be arriving in Casgrovina after today, we all know that. So, we might as well tell you what else we found and have been able to piece together, evidence and speculation. From within these four we are able to see into the center one, and, it's very different indeed. Doctor Weingard, would you like to explain?" Weingard indicated another of the drawings on the board and elaborated, "Now, arranged around the inner surface of this center sphere -- actually slightly ellipsoidal -- and jutting out into it, are nine separate, hemispherically-shaped enclosures or balconies, all on the same plane as the structure. At the center, fifty feet in diameter, is a spherically shaped hollow, visible from the enclosures through translucent, unknown material. And at the center of this hollow, approximately twenty to twenty-five feet in diameter, is another sphere suspended in what appears to be a vacuum. The balconies connect through their respective conduits to the spheres we have examined thus far, and, because of this connectedness, each contains the same gaseous assemblage or atmosphere as those respective spheres. "As far as the atmospheres are concerned, as was stated before, we don't yet know of what elements they are composed or how, precisely, these elements arrange themselves. It may very well be that the complex and varying internal geometry of each sphere -- its ecological morphology -- has a definite affect on the structure of its respective atmosphere, if we can call the conglomerations 'atmospheres,' which in turn, as was mentioned before, may very well affect the color frequencies of the designs, some kind of feedback relationship, it would seem." "Sir," asked a journalist in the front row, "how is this smaller sphere able to remain suspended?" Weingard turned a little pale, gathered himself, and replied, "We don't know, plain and simple. We can see no force of any kind responsible for its ability to do what it's doing." Tolstoy and Weingard turned their backs on the silent crowd and spoke quietly to one another, gesturing pictures in the air. A man entered from the side of the low stage and approached the two on the dais. They shook hands, spoke softly, then Tolstoy turned to the crowd of silent journalists and said, "I would like to introduce Doctor Horace Noble from Stanford University. He, as you may know, chairs the Mathematics Department and has written extensively on fractal geometry and information theory." This brought a few self-conscious guffaws. Science writers generally stay away from mathematics, as a rule; not as sexy as cosmology, black holes or relativity paradoxes. "Perhaps not. None the less, he has some things to say about the edifice's designs." Doctory Tolstoy relinguished the podium to Doctor Noble. Short and stout with thinning hair, looking more like a bartender than a mathematician, he nonetheless spoke with focus and clarity, "I have only spent three weeks examining the designs in each of the four spheres. The patterns on the central sphere hovering in the hollow are far more complex and, seemingly, of a different character than the four we have yet examined. For one thing, the lights are white, as you would expect. Yes, this smaller sphere is mapped with myriad interconnecting patterns; what they may mean and how they relate to the designs of the separate outlying spheres has to await further study; when, I can't say at this time." He turned his head to speak briefly with Doctor Tolstoy, who nodded back, then, visibly ratchetting-up his intelligence, he spoke, "My work in fractal geometry has not been in developing the geometry per se, but rather determining and classifying fractal patterns across parallel idea-fields." More guffaws. "Could you break it down for us fractal-challenged, Doctor Noble?" a voice asked for all. Resting his forearms on the shelf, Noble leaned forward and said, "O.K., now, interrelationships in the arrangement of a group of stars can form a constellation, we name these: Orion's belt, the Bear, the Big Dipper, and so forth. We have a schematic of the picture in our head and by applying this to the heavens we are able to pick out the grouping of stars that it maps to, if we know what to look for, a big if, and where, its frame of reference. The picture in our head has to be based on knowing what to look for, otherwise we have little chance. "Practical interpretations of symbol systems, the patterns the networks of lights form, without a Rosetta Stone, present a formidable challenge to the imagination. These designs could very well be representations of abstract concepts, a library, a language based on a system of thinking on an order of magnitude beyond our ability to even characterize, let alone, unravel. The interconnections and relationships are of a countably infinite number and degree of nonlinear complexity. "Therefore, applying what's known may not be sufficient, in fact, probably isn't. Accordingly, we have to resist imposing or overlaying known patterns in order to see clearly what's there, what these designs may be about; no predispositions, in other words. From a mathematical perspective, we have to suspend any and all coordinate systems or frames of reference. Could they be maps of the stars; do they represent fields of study, a collective knowledge, using network patterns very unlike our use of numbers, alphabets, and pictures; are they some kind of engineering schematic for an organic machine that operates without moving parts? We don't know yet, I don't know yet, but, embedded in the larger designs I have been able to see some parallel similarites across scales, components possibly, modules, I don't know. Further study is required; we have only scratched the surface of understanding." For a moment it seemed his eyes pinwheeled, but perhaps it was the poor lighting. He continued, "After we've examined the other five spheres we'll be able to make more informed comparisons. But I can say this much, in my work I've learned to follow my instincts and intuition, to try out hypotheses, as it were. Because of the connecting tunnels between the inner sphere and the others, I have a sense that all nine separate designs must work in consort somehow. For instance, if we were to layer them in all possible permutations, what would we see? This would be a job for the supercomputer at Stanford. Or, do they hook together in some predesigned sequence or juxtaposed fashion? There are many other possible arrangements, of course, they could be tesselated in some way. "And then we're back to the problem of perception: how many different ways can the same set of parts be perceived, depending on the frame of reference? For example, a recipe, a set of ingredients, has practical significance only when integrated to the proper proportions and in the proper order; considering each ingredient on its own would therefore not be very insightful. A ladle is a ladle, whether it's in a pot of soup or the northern night sky. We grope in the dark, but we have some tools. These are some of the problems we face. "I have requested the mathematical societies from around the world to submit to their members a request for assistance; I anticipate no shortage of qualified volunteers. We will also have use of any and all extra computer power from MIT, Harvard, Cambridge, CERN, and other university and government faciities, including NASA and the European and Russian space agencies. And this is just the beginning." Retrieving a folded sheet of paper from his inside coat pocket, he handed it to Doctor Weingard; then, with a quick nod to Tolstoy and the other team members at the table, stepped off the dais and walked quickly off-stage and out the side door. No one had a chance to ask a question, even if we had known what to ask. Immediately afterwards, two men dressed in dirty orange coverals strode from the other end of the stage toward the group of seated scientists. Doctors Tolstoy and Weingard approached to listen to their excited talk. Eyes lit up, jaws dropped, smiles of wonder appeared on their faces. Tolstoy approached the podium and declared an end to the press conference. Then, following the two techies, he, Weingard and the rest of the team left in a hurry. |

Horace Noble, the lead mathematician on the investigation, believed at the outset that he had seen component similarities between patterns, but then later recanted, saying it was only the wishful perceiving of someone hoping for simplicity where it most definitely is not.

Glipter sat up, banging the bottom of the recliner into place; irritably tossed the cut-out piece of newspaper onto the side-table, finished his drink and, turning to glare down at the clipping with a mix of contempt and annoyed frustration, put the glass in the center of the coffee ring. With one movement he was on his feet and out the door, grabbing his rain-jacket on the way - Siberia in the summer. He was looking for something, he knew not what; all he knew for certain was that he needed much more information, but from where, and what kind?

SQUALL

Though low hazy clouds drifted in from the sea, it was still daylight, and would be for weeks to come; summer solstice was on the cusp. Hans Glipter, science interpreter for the layman, now become investigative reporter, stood on a low ridge overlooking Nagayevo Bay; his trailer had found a home in the boatyard north of town. No Casgrovina fishermen were bothering to work their boats, so it was relatively quiet. He breathed the freshened salt air deeply, the bourbon stiffening his bones and quickening his blood. He shook his head and then asked out loud, "Okay, for starters, what the hell was going on here, right here where I'm standing, 600 million years ago? What?"He listened to the breeze whistling through the riggings of the boats nearby, a symphony of sounds, bangings, thumpings, and rat-tat-tat-tats in quick succession; the bay below looked like the skin of an orange -- low pressure moving in. If he studied the equations describing the scene before him, he thought, would he see the incipient wave crests about to form? Would he feel the salt spray and smell the turgid air? Or would they just be abstractions of idea relationships? Hidden potentials? Empty of substance and meaning? How to see, that's what he must learn, how to see the patterns forming.

Behind him, footfalls scraping the narrow, gravelly road that ran along the edge of the boatyard caught his attention, but he didn't turn, didn't need to. "Glip, Glip, old man, are we about to be rescued from this accursed rock by a boatload of lusty women? Don't just stand there, help them, for God's sake, help them." Laughing at his own joke, Tommy "Turbo" Geneva, Glipter's friend from the old neighborhood and present assistant, pulled up alongside, dragging his feet to a halt. Black curly hair down to his shoulders stuck out from beneath his signature black beret, climatically complemented by a knee-length down coat and cowboy boots.

Without seeming to move, he produced a pint of bourbon, not altogether full. "Here," he said, "you're gonna catch cold with that little bitty rain coat." Hans grabbed the bottle and took a swig, still staring out. "You know, Turbo," he said, just above the sound of the sea and the gulls, "I think I may be completely out of my depth here, we all may be completely our of our depths. Nobody I've talked to as yet has a genuine clue as to what the edifice is about; some of them even seem spooked, like they don't want to know, afraid of what it may mean, who they really were. Everybody's mind is torqued around one major fact: 600 million years ago there were entities in the Universe capable of building that thing, of designing it for some purpose we know not what." He took another swig. "Had it been orbiting the Earth for billions of years only to crash land, for whatever reason? What do we know? Nothin'." He turned his face up to the approaching squall and bellowed, "We know nothin,' man. You dig what I'm sayin'?"

Hans took another pull then handed it back, turning to smile his wild-look as he did so. But his "thank you" was blotted out by the roar of wind and a dust swirl of decent proportions. Not fifty yards down the boatroad that ran parallel to the rocky beach, on a gravel-dirt clearing reserved for haul-outs, a work-helicopter from the excavation site landed like a bee on a flower, then immediately shut down.

"What's this?" asked Turbo, always suspicious and justifiably paranoid. "Pizza delivery? I didn't order a pizza. Did you?" The door slid open on the side of the chopper facing them, two figures stepped out, both about the same height, one dressed in a black insulated jumpsuit and wool cap, the other in a long old cashmere coat, a Russian hat propped high on his head. He held something in his right hand, small and black, but it was too far away to make out.

The two walked slowly up the slight grade towards Hans and Turbo. Turbo took another sip, tried handing the last of the bottle to Hans but was waved off. They stared intently and half-expectantly at the approachers; measuring, reading, automatically and subliminally -- street kids. The jumpsuit held the other's left elbow -- not a sign to breed anxiety, ordinarily. But signs were what Hans was looking for, and so was sensitive to every nuance.

The clinging mist moved onshore -- precipitation without direction -- wavering visibility, dressing the smooth and the sharp of the stones with a sparkling liveliness. Greys and browns and blacks and whites intermingled and glistened, stark graininess outlined the careful movements of the advancing pair.

Suddenly Hans recognized the old man's gait. With a quick, almost boyish smile, he roared, "Professor Samuelson, my God, whenja get here?" He strode past his friend, down the hill toward the visitors, eliminating the distance between them with a rush of warmth and a strong, appreciative hug. It was a bit more than the reserved and dignified curator was expecting, Hans realized through the bourbon, so he pulled the reins in a little, stood erect, and continued in what seemed like a more respectful tone but was, nonetheless, laced: "How are you doing, Professor? Still got that coat, I see." Leaning forward, he whispered, "It'll make a fine addition to the museum someday."

The old Professor nodded, smiled, locked eyes with Hans and in the same vein replied, "Why thank you, Hans, but it's already been arranged. The coat's to hang and I'm to be in it, stuffed and mounted." With that he laughed like the tough field worker he used to be, bringing his everpresent pipe to his lips and attempting to light it in what had now become a steady drizzle.

During his years at Berkeley, Hans had helped pay for his education by working in the University's Natural History Museum as a kind of glorified stockboy. Professor Samuelson had only recently been appointed curator at that time and was therefore his boss. He showed concern and interest for what Hans was doing in school; something he wasn't getting from his overworked mother, his father having passed away when Hans was just a boy. The Professor had even managed to talk Hans into taking a paleontology course as an elective one year, a class he mostly used to catch up on his sleep, an indulgence now regretted. He had a mental block, he figured; paleontology to him had to do with moving specimen cases and large cast models of dino bones; monitoring the environmental controls in the storage areas; helping to set up exhibits; maintaining the grounds; cleaning, cleaning, and then more cleaning -- manual labor. So he always stayed away from it in his work. But now, he needed to know and understand what happened in the distant past, and providence may have provided.

Turbo, standing alongside, ignored the reunion, choosing instead to stare in silence at the Professor's companion. She had abruptly removed her wool cap and was shaking her long curly red hair -- an arresting development -- like a flair going off in a coal mine. Hans couldn't help but stare too. "Excuse me, Hans," said the Professor warmly and with some amusement, "this is my daughter, Rose Marie, she's been here for weeks, I thought for sure by now you would have at least seen her." Drawing on his unlit pipe, giving Hans the onceover, he continued, "But I kind of sense that you haven't."

She smiled while Hans stumbled for words. Red-brick hair, hazel eyes, full red lips, high-boned cheeks with just the right tinge of rose, seemed the only real color in an otherwise bleak and grey-dreary surround -- the house just landed in Munchkinland. "No," he finally said, "I haven't had the pleasure. What outfit are you with, Miss Samuelson?" He stepped closer, breathing deeply as he did. "There's an inner circle, a special group covering different areas; they've hit on something, I don't know what. Would you be one of those?"

Startled, looking suddenly very concerned and professional, color fading from her cheeks, she asked, "Nobody's supposed to know about that, it's totally secret; how'd you find out?"

Now it was Hans's turn to look amused. He stretched the moment, drawing it out slowly, enjoying her fresh vulnerability. "I didn't," he replied matter-of-factly. She blushed, the Professor smiled and looked towards the bay. For an instant, Hans glimpsed beneath her surface toughness and liked what he saw.

A low, guttural throat-clearing interrupted the tableau. "Oh, excuse me; Professor, Rose Marie -- my friend, Tommy Geneva, also my assistant and facilitator." Turbo, ignoring the Professor, took her hand in his, carefully shook it a few times, and said with a smile and many nods, "Thank you, thank you." Her previous good humor returned with a smile of her own. Turbo was disinclined to let go of her hand, but eventually relented.

"Rose Marie, do they call you that, or is it Rosie, or, what do you like?" asked Hans, wanting to start again on a new foot. Though still immersed in embarrassment, she decided to forgo it for now. Collecting herself, stiffening her back, she replied, "Well, Dad calls me Rose Marie and sometimes Rosie, depending. Rosie's fine."

"What about that nickname of yours?" the Professor needled. She laughed; he continued, "she likes to climb rocks, Hans, for God's sake, cliffs, in the wilderness, so, the crazy people she associates with call her Rocky, Rocky, of all things."

Quickly turning towards the bay, Hans laughed just in time to get a gust of salt spray in the face. He cursed under his breath, and with a grimace, said, "O.K., Rocky, I have a trailer not fifty yards from here, quite comfortable and dry, over there in the boatyard. What do you say we get out of this,..., wet stuff? Professor, you've just arrived, right? Are you staying somewhere? I can take you later. But for now,..."

"Yes, by all means, I've had a hell of a long and eventful day. Nowhere yet. I knew you were here and wanted to see you, so the good people at the site offered this helicopter which I, personally, prefer not to ever ride in again. Rosie, or Rocky, rather enjoys seeing her old Dad cringe, however. She, of course, likes it. I don't know where I went wrong, Hans."

Turbo was already on it, heading for the copter to tell the pilot it was okay to leave.

"Do you have any luggage, Professor?" asked Hans.

"Well, I'm not sure, the airport is madness. No, nothing with me; I despise carry-ons. I have to believe my bags are there somewhere, as soon as they find them they'll be sent to the paleontology house, I was told, wherever that is; I have only the vaguest of directions."

"I know where it is, never fear, we'll get your stuff tomorrow. But for now, I have plenty enough room," Hans said, extending his right arm with all due graciousness in the direction of the Airstream, barely visible in the grey drizzle.

As Turbo strode up, they turned to walk, the copter's roar drowning out further conversation. Hans, the Professor, Rocky, and Turbo, paced it out to the crunch of gravel as the wind began to rise and the skies grew dark -- a squall was coming.

AIRSTREAM SANCTUARY

The Airstream was divided into four compartments plus a small but functional bathroom. At one end was Hans's bedroom, the door opening onto a narrow hallway, at the other end was the bathroom. Adjacent to the 'master' bedroom was another just large enough to accomodate a single bed, a bureau, a side-table, and a closet -- Turbo's crib. Next in line was a den-study-workplace for Hans -- the communications center -- computer with wireless internet connection, radio phones, and a satellite television. Fully half the length, the remaining space, was where Hans had been spending most of his time of late -- a living room fitted with his favorite leather recliner, a two-person couch, a high-backed bamboo chair -- Turbo's choice -- and a kitchenette off the foyer against the wall.A thick Persian rug lent warmth and civilization, as did three lamps of various designs resting on mahogany tables; Hans hated overhead lights, so there were none. Impressionist prints in simple wood frames adorned the fir-paneled walls; the windows were shuttered from without; soft tapestry curtains covered them within. The bar was in the kitchen area.

Turbo, bootless and wearing one of his many Hawaiian shirts, busied himself making drinks for all -- a rum and coke for Rocky, a snifter of cognac for the Professor, Wild Turkey and coke for Hans, and for himself, a shot of bourbon and a beer.

When everyone had settled in, the sound of wind and rain lending womb-like comfort to the warm surroundings -- a heater hummed soothingly from somewhere unseen -- Hans started right in with a chide. "Professor, where have you been? I'm amazed and surprised that one of the most knowledgeable paleontologists in the world has only just arrived."

"Well thank you, Hans, for saying that, but when I first received word of this incredible discovery I was in the midst of several projects at the museum; then there are my classes, my students, can't let them down, you know. I did keep in touch with the paleontology contingent here as well as an e-mail correspondence with others who also were not able to get away from their duties. But, school is out for the semester and the last of my projects I turned over to some hapless graduate students needing some hands-on education. You remember what that's all about, don't you?" he laughed quietly. "I got here as soon as circumstances would allow."

Hans laughed mildly at the friendly jibe. Taking a sip of his drink, he continued, "Your expertise, Sir, I believe, is required. I think everybody, by that I mean the press, the media, and some investigators I've spoken with, are going down the wrong lane. I mean, I think they're ignoring the larger picture, the background, in order to study the most prominent features, the designs and the edifice itself. I know that sounds ridiculous, after all they are the obvious choices of study. But, I've been getting misinformation, I can tell, from some people who seem to be holding back."

Rocky lowered her head, then raised it quickly to sip her drink. Turbo caught it. Leaning forward, he asked, "Miss Rocky, what's with this secret organization you let slip? Sounds like undercover stuff to me. Who's in this group? What have you been working on? Have you found any green aliens, any old magazines from the home planet? C'mon, Rocky, what gives?"

Hans jumped in, "Turbo, Turbo, that's not very polite. I'm sure Rosie has reasons for secrecy." He turned to stare at her with humor in his eyes.

"I do," she responded in a quiet voice, making it sound almost ominous. "But," turning to glance at her father, "I've already told Dad everything we know thus far. I felt he had to know if he's to properly study the problems we face. I'm glad you're here now, Dad. As Hans said, we need your expertise, and your imagination."

Taking a pull on his still unlit pipe, he leaned back on the plush couch, and said, "Hans, I greatly admire your choice of paintings. That's a Monet, isn't it, one of his earlier works? And these lamps, my, oriental, porcelain, must have cost a pretty penny. And where did you get this wonderful rug, my goodness, a person could get lost in the patterns and texture." He took a sip of cognac and then carefully rested the snifter on the side-table. Turbo leaned back also, the creaking sound of shifting bamboo filling the room. Hans and Turbo sat back, listening to the wind and the rain and the faint humming of the invisible heater, waiting patiently. Rocky stared at the floor, tacitly approving the inevitable; in her heart she wanted the world to know what they had so far discovered and surmised, but still, she sensed potential danger in the knowing.

"I've followed your career, Hans," the Professor said amiably, "I wish you had remained a teacher but, not enough freedom, too conventional for you, I suppose. You like to travel, explore horizons, fathom the unfathomable. I read your piece on the bogus cold-fusion experiment; you were way ahead of the pack on that one, as usual. And the series you did unraveling the mysteries of string theory, brought it right down to the layman, excellent. Your perspicacity will be seriously tested now, Hans. This is a challenge that, perhaps, not even you can master. Some of the best scientific minds in the world are here in little Casgrovina right now. They know their stuff too, but, their failing is the box, they have trouble getting outside of it, you don't seem to have that problem, quite the opposite in fact." The Professor, looking distant and bemused, took another taste of cognac. The rain had intensified, hammering the roof and shutters.

"My daughter, Rose Marie," he emphasized the name as he glanced her way, "is a mathematician, a topologist, and a darn good one. She's been teaching at the University of Chicago for, what is it now, six years?" She nodded yes but remained silent, as did the others. "Doctor Fitzsimmons, Chairman of the math department at M.I.T., invited her to be a member of his special group -- the Puzzle Masters they call themselves. At present there are fifteen, a few added only recently, others will no doubt be brought in as the need arises. I've seen the press releases the P.R. team's handed out, you probably have them; it's mostly falacious, Hans, intended to buy time and assuage fears. But, as far as that goes, it seems to be having the opposite affect, generating uncertainty and anxiety in general." He sipped cognac, a warm rosey hue tinted his otherwise tanned features. It'd been a long flight and he was visibly tired.

Hans took the pause as opportunity to speak, "Professor, what is going on? I have the fact sheet right here." He reached down to retrieve the legal pad he'd previously stuffed next to him in his chair. I would like to go over this, one fact at a time, to get your take and any corrections, and also if there are facts not on the P.R. sheet you feel worth mentioning. But, you're obviously exhausted from travel. You're welcome to use my bedroom, I can sleep in the den. Rocky? I have extra blankets if you'd like to crash out on the couch. We can begin fresh tomorrow, after breakfast, if you'd like. Turbo does most of the cooking, he's not bad when he's in the mood. Aye, Turbo?"

They all snickered; Turbo grimaced but with a twinkle in his eyes, kicked back his shot, then slowly stood to bring his tall, muscular frame to its full height. "O.K., I see where this is goin.' Who wants another; the bar's open." The wind and rain continued its assault unabated; the heater hummed. Talk meandered along more mundane trails, feelings and minds mingling, relaxing -- an old custom among humans.

Rose Marie, aka Rocky, was a strange mix. When she wasn't traveling through multi-dimensional topological spaces without the geometer's net of a coordinate system, she was traveling through back-country searching for cliffs to climb also without the benefit of a net. One more year at U. of Chicago and she would be eligible for tenureship. She was single; lived in an apartment within walking distance of the campus, a distance she usually biked to keep in shape; liked Italian food and pizza, red wine and candlelight; was intelligent; possessed of her father's honesty, humor, and earthiness -- and unself-consciously beautiful.

The Professor, Doctor Samuel Samuelson, a parental joke, no doubt, which the Professor nonetheless enjoyed, had been a field paleontologist for the U.S. Geological Survey for the better part of twenty years. He started off chasing dinosaur bones like everybody else in the 60's; the field became overpopulated, so he began to look elsewhere. One day, while on vacation, he was going through some old plates in the archive of the Natural History Museum in London, when he came upon prints of creatures from the Ediacaran Fauna, approximately 620 to 510 million years ago. On every continent except Antarctica, they flourished, these bone-less, shell-less, mineral-less creatures, glued to the floors of warm shallow seas, passively partaking of food, phytoplankton, for millions of years, increasing in diversity, size, and population, then dwindling, dying out, shrinking in size. No one knows for sure how long this cycle went on. A few phyla continued through the Cambrian Period, but otherwise it is accepted that the Ediacarans died out at, or prior to, the transition to the great Cambrian Explosion of around 540 million years ago, the advent of shelly bio-mineralisation -- calcium carbonate, calcium phospahte, and silica -- all three mineral compounds of what presently exists to generate hardness -- bones.

He was fascinated, spell-bound, inspired to wonder -- he converted. The Precambrian Eon called, and he dove -- now, his expertise.

After twenty years in the field in places like northwestern Australia; the Ediacara Hills, Flinder's Range north of Adelaide, South Australia; southwestern Greenland; South Africa; the Burgess Shale in Northwestern Canada, and a host of others, searching and inspecting, cataloguing and analysing new and varied species of Precambrian and early Cambrian life, he retired to take a faculty position at the U. of California, Berkeley. At first he just taught, but he quickly grew bored with mere academic pursuit and needed some hands-on activity. One request was all that was needed, he was appointed assistant curator to the University's Natural History Museum.

After three years, the director retired, and Doctor Samuelson assumed that position. As head curator, he brought in a whole new paradigm, reinvigorated and transformed the entire format of presentations and content. That was 13 years ago, when he first met Hans, the student/part-time laborer. Now, he's here, and he has a hunch, but he's not ready to tell -- he could be wrong.

Tommy 'Turbo' Geneva didn't say much about himself. He liked mystery, to keep people guessing, shifting personas at a glance, in a single heartbeat. Growing up on the streets, this was an art form best internalized. He could be eloquent and well-read one moment, a seedy, hedonistic rowdy the next, whatever was required. But, even though he loved to laugh, his main overall underlying posture was one of abject, deadly seriousness. Hans and he had been part of a group who ranged together when kids; traveled the subways; hung out in the neighborhood, in the schoolyard, on the corner; went to the same high school; played football every day, it seemed, in the fall and winter, in the snow and ice; suffered through loses of family and friends; and drank beer on friday and saturday nights.

After high school, Hans attended Berkeley; Turbo stayed in the neighborhood, getting a job at the Philadelphia Navy Yard as an apprentice pipe-fitter. When Hans was home on break, they would get together again and hang out. They had lost touch while Hans was at Michigan State teaching physics, a position he quit after five years to take the job he now has, a stone's throw from Philly. On invitation, Turbo reunited with his lifelong friend in D.C. where he was ostensibly hired as Hans's assistant, but, in truth, it was so they could 'hang out' and travel together.

Enfolded in their own thoughts and feelings, the four slept through the stormy night, oblivious to the transformations set in motion.

Though Rocky slept tight on the couch, its length sufficient but just barely, her dream-self traveled.

Her hosts spoke to her, or so it seemed they spoke, in a friendly manner as one might expect from tour guides. Wraparound windows surrounded her from top to bottom on the bridge of the dimly-lit, cavernous ship. She knew it was a ship without thinking about it, the way we do in dreams, we just know. There was much activity around her, silent and smooth, practiced and professional. A voice from behind politely directed her attention to the front portion of the huge curved window through which she saw nothing but the blackest black. She had no sense of movement, no objects to gauge it by, no frames of reference. She was being told to watch closely; relaxed and unafraid, she did as instructed.

Suddenly, in the midst of the void, as though through a film of some kind, a bubble of unknowable proportions was being blown through a membrane that had materialized all around the ship; she became instantly lost in wondrous amazement. She thought that the membrane must have always been there, and felt sure of this observation. What she saw form as the completed bubble moved off to her right was even more astounding -- a universe of galaxies and stars and nebulae coated the surface of the bubble. From behind she heard, or perhaps felt, murmurs of delight and appreciation, praise, even, for the Dark One.

Next, another much larger bubble was formed, it too moved off but in a different direction, if direction made sense here, she thought. Finally, one was produced to the sounds of genuine enthusiasm and cheers. A voice from behind whispered as though to a child, "That is yours. How do you like it?" She was spell-bound and awed beyond comprehension. Countless galaxies moving and churning; nebulae birthing stars, brightening through every color imaginable; single stars traveling their own courses in the spaces between; a kaleidoscope of infinite, colored patterns and designs. No one moved on the bridge, all activity and sound ceased; she gazed around but could see only shadows, hard and soft angles. She stared through the window, transfixed, overcome to tears.

A loud buzzing noise permeated the space of the bridge, annoying and everywhere. She awoke, the dream still in her mind's eye, that halfway point between wakefulness and sleep. She tried to hold on but it was no use; the ship, the bubble universe, the feelings of joy and wonder, all vanished; to be replaced by the sight of a multi-colored dragon. She focused. Turbo stood in the kitchenette, emblazoned across the back of his knee-length, blue velour bathrobe was the embroidery of a wild-looking dragon; the door of the microwave open. He closed the door as quietly as he could, then glanced over his shoulder sheepishly, mumbled a gravelly apology, cursed the microwave, grabbed a jar off the counter, unscrewed the lid, spooned out some instant coffee, poured it into the steaming cup, recapped the jar, and while stirring softly, walked back to his room.

She watched the proceedings as though in a bubble of her own, separated by a thin film, unable to form words, engrossed in the details. Rolling to face the back of the couch, she tried to fall asleep again, hoping to renew the dream, but it was too late, she knew. A strange forlorness and melancholy possessed her; she wanted to cry at some unknown loss, but the tears wouldn't come. Her memory could not hold it, the dream faded, evaporated, by pieces, like steam rising. Her eyes closed, she lay very still, feeling like a child again.

Everyone would be up and about soon, she thought. She groggily roused herself to change in the tiny bathroom from a pair of Hans's pajamas into her standard jeans and flannel shirt; loss and sadness still dogging her. But the joy and wonder she had felt had an unseen effect -- seeds were planted, doors opened.

THE DIG

Monday Morning.Alex "Bull" Mynsky, chief mucky-muck, overseeing coordination of efforts on the project, or 'the Dig,' as it was commonly referred to, was not having one of his best days. His presence had been requested almost immediately after the discovery of the edifice. A former General in the Russian Engineer Corp, he had the 'bona fides,' as they say, for a job of this scale. The first major operation had been the pouring of a monstrous slab of concrete over the surface of the earth where the edifice stood, embedded in it were miles of copper tubing through which hot water circulated. A translucent geodesic dome of carbon-reinforced plastic covered and protected the alien structure from the uncertain Siberian weather. The grid of radially-connected two-inch aluminum tubes supporting the hundreds of plastic sections rose to 150 feet at the center post. Through the tubing, miles of wire, cable, and phone lines snaked their way. One-meter wide parabolically-shaped halogen lights hung from the tubes, positioned to afford maximum light throughout -- an interferometer of light. Six-inch cylindrical aluminum posts, strategically arranged, reinforced the ceiling; wiring fed down them to accessible outlets. On the periphery, massive generators continually hummed, supplying power.

In addition to heat produced by the hothouse effect, ambient air temperature remained within three degrees of 'room' by the concrete-encased copper pipe. Scaffolding was everywhere and had the look of permanence. Small trailers made into makeshift labs and shops appeared behind every curve. Hundreds of people -- scientists, technicians, engineers, mountain rescue teams, electricians, laborers -- a whole community with one noticeable exception -- no media people. This was a private dig, and 'Bull' was under strain to keep it that way.

The scientists ignored his requests not to reveal sensitive material to the media. They usually replied with amused smiles and polite nods; they didn't understand. And the workers, local fishermen mostly, going into town, getting drunk and shooting their mouths off about what they saw. How much longer could this go on?

He charged out of his office in the main trailer at the head of entry to the site, and, disdaining his golf cart, continued in that vein as he crossed towards the far corner of the Dig. As he passed the outlying sphere, a man wearing a white hardhat, white shirt, wide tie, pocket protector, clipboard in hand -- him -- approached at an oblique angle, a look of flustered anxiety and concern flushing his face.

"Bull," he said almost too softly, "I mean, General Mynsky, sir, we need to talk."

"Can't it wait? I'm off to chew somebody out or fire him, whatever it takes; can't it wait?"

Recovering composure, the engineer spoke with genuine determination, "No, sir, it can't. You really need to see this."

Surrendering to his lot in life, Bull accompanied the agitated engineer to a long metal table covered with what appeared to be white sheets, adjacent to the center sphere looming overhead, its upper half completely out of sight. Amongst the jumble of computer screens, phones and paper work, the engineer brought Bull's attention to a small mobile screen leaning against a stack. He handed it to Bull. "This monitors our electron photomicrographic scan of the atomic lattice structure over the entire surface. We have sensors positioned to constantly read for any changes or fluctuations that may occur. The magnetic ordering is layered by spin states, the unit crystals build-up, so to speak, from ..." He stopped to catch his breath. Raising his glasses with one hand he brushed a finger under his left eye, buying time.

"Well!" Bull inquired, "so what. What exactly am I looking at?"

The engineer removed his hardhat and replied, "What you see there, on the screen, is the frequency modulation of the assemblage of quantum properties accountable for the precisely ordered arrangement of the surface material. That red indicates the carrier wave's frequency and amplitude as an historical reference, it's remained the same since we began readings six weeks ago." Another long pause, then "The blue indicates those features now, as of early this morning; I could give you the exact time but, I don't..."

"Damn it, son, get to the point, I have things to do."

"We first performed a thorough diagnostic on all our equipment; there are other reasons for the appearance of such a phenomenon. But hardware and software are running true. However, ..., the point is that the surface of this sphere has begun to alter its atomic arrangement, we don't know why or what it may mean. We're continuing analysis of the precise structural configuration; it is still slowly changing - without violating the hulls integrity. Amazing."

Bull did not share his sense of wonder; all he saw was trouble on the horizon. "Come to my office with a status report as soon as there's a status to report. And don't be bringing me over to look at your damn screens anymore. O.K., son? I'm a busy man." He handed the monitor back, took one hard look at the preoccupied techie, then spun to return to his trailer, convinced beyond doubt that the project was slipping away from his grasp, that other forces were taking control.

Disgruntled, he pushed his way through the door. Sitting around his desk were three men with serious looks, three he liked, scientists who knew how to keep their mouths shut, a little too shut perhaps, he often thought. He gave them no more than a glance and perfunctory nod as he roughly opened the top drawer of his filing cabinet where he kept a bottle of vodka. After pouring a drink and momentarily enjoying the silence, he asked, "What's up, gentlemen, you have good news for a change?" Sarcasm was lost on these, he knew; they had little sense of humor.

Doctor Fitzsimmons, seated at the far end of the desk, spoke in his usual clipped manner. "We'll get right to the point, Bull, we may not have a lot of time to squander."

"Good, please do, it would be refreshing."

"We've been concentrating our efforts on the five spheres opened after the disasterously reckless way in which the first four were attacked, their atmospheres remain intact and do, indeed, have an influential effect on the behaviour of the lights making up their respective designs."

"Behaviour, you say? What does that mean?"

Fitzsimmons ignored the question and proceeded unperturbed. "In sphere P-5 we have been able to enter all the rooms, if that they be, taking video and pictures from various vantage points; with nothing to hold onto, it was painstaking work, I assure you. We ran the footage and snaps through a Cray, here are the results." The man sitting in the middle, Doctor Jennings, spilled a folder of diagrams and drawings onto Bull's desk.

Bull stared at the tiny hill of arcane schematics and said, "Could you sum it up, please, I really don't have time to go through all this stuff, if that's what you expect? Words, gentlemen, speak to me."

Pointing with a pencil at a tight nest of lines and symbols, Jennings proceeded, "The Cray analysis, examining the vantage points from all the rooms, has determined three sets of focal points. When these three focal points are arranged colinearly, as you see here, the line intersects the design here." He circled an area where lines drawn from every direction met. "In each of the five spheres we've examined the rooms are arranged differently, yet, we've arrived at the same results for each. Apparently, hypothetical entities, and we have no idea what kind of entity we're talking about here, we can only speculate on what they could not be or look like, apparently, three groups from any sphere acting as one could be in contact with the main design on the wall of their respective sphere at their mutual intersecting point, or, alternatively, it could have some influence over them."

"Or," said Bull dryly, "there were no entities, and each of the rooms is but an extension of a wall design, like chambers of an engine, or a nautilus. They work together somehow, three different gears churning as one to produce, what? And what was this again about the behaviour of the designs? What's that all about?" Bull took a drink and sat back. The Puzzle Masters knew more than they were saying, he thought; they must have many scenarios to explain this stuff, not just 'hypothetical aliens.' He waited. They wouldn't be here telling him this much if they didn't need or want something in return. So he waited.

The third man, the one who hadn't spoken yet, got up from his chair and paced to the back of the office, hands in pockets, paused, then, walking back, began "We've compared the activity of the designs in the four spheres that were opened prematurely, before we had a safeguard system in place, with the other five. Without their respective atmospheres, the designs in the first four are relatively quiescent, that is, we've detected minimal quantum fluctuations at any specific location or when considering a design as a whole.

"But not so in the last five, P-5 through P-9. Using digital cameras of the highest pixelation available, translating the pixels into bits per unit micron, and then sending this information through the Cray, we've been able to ascertain very definite patterns within patterns, as well as their transitional modes. For any given design, the subtleties of transition can hinge on a single electron spin of a single atom making up a boundary. As a result, as you can well imagine, with a design as huge as these, composed of, as yet, an undetermined number of lights, or illuminations, in complex arrays and interconnections; the sheer number of possible patterns and pattern relationships is infinite.

"And, of course, what does it all mean?"

He sat down, hands still in pockets, stared at Bull, and said, "That's their behaviour."

Doctor Fitzsimmons broke the silence that had humorlessly drained the room of life, "Up until early this morning, the rate at which the patterns shifted remained constant, varying slightly due to inevitable temperature fluctuations, as we come and go and place instruments and cameras, sterilized but nonetheless, a heat source. But this morning our online feed consolidating all readouts from our digital cameras and spectrometers, detected and amplified on screen a sudden and discontinuous increase in the rate of transformation. We have yet, and I mean this, we have yet to find the Rosetta Stone to decipher the meaning and significance of the shifting patterns. We have been able to classify topological types, a kind of taxonomy, but, as Doctor Weingard said, there's a lot of them."

Bull emptied his glass and quickly refilled it. Remembering his conversation with the engineer, he stood and paced behind his desk. "What about the other four spheres? Any activity there?"

Jennings volunteered, "No, no change; and that's odd."

"Odd!" Bull roared with laughter. "Odd!" he reiterated in the same octave. "This whole damn thing couldn't get any odder if Zeus himself were to show up and take back his toy. What I want to know is, where is all this going? Why are you here in the first place? I hardly ever see any of you gentlemen and now -- three at once."

Fitzsimmons put his coffee cup on the desk and leaned forward, putting elbows on knees, and softly and quietly said, "The point at which the three groups of any given sphere impinges on a design never partakes of any transformation, it remains fixed, it maps to itself, so to speak. By the simple act of measurement, we may have inadvertently set in motion some kind of initialization sequence, a revitalization, or a failsafe mechanism, we don't know. But they, the spheres, are definitely undergoing a change, which indicates, of course, that we are not dealing with a dead artifact from some alien civilization."

He picked up his cup and leaned back. "You're in charge of this operation. It's on Russian soil and you're their representative, you have the authority to shut it down if you feel it's necessary. But you're also a cultured and civilized man, you appreciate the magnitude of what we have here."

"Oh no, Doctor, I don't understand; trust me on that, it's way beyond my puny intelligence. I'm a cossack, we roam the steppes for the fun of it. Alien spaceships; cryptic, complex designs on walls of spheres a hundred feet high,...; no, Doctor, I do not understand."

Jennings leaned forward and said flatly, "Nobody does."

Fitzsimmons continued, "I didn't say understand, I said appreciate, and you do, obviously, by what you just admitted. That's how we all feel, but, we must continue our study, our research, to try to discover the purpose and significance of the edifice. And to fathom the nature of whatever civilization created it, and where they may be now?"

He sipped coffee, then said, "We felt compelled, by our readings this morning, to inform you of the situation; a changing one, I might add. I've called for a meeting of all of the lead scientists on the project, they'll inform their respective team members. You're invited as well, please come. Eight this evening at the community center downtown. Security is already there readying the place."

Fitzsimmons, Jennings and Weingard stood as a group; Jennings gathered the drawings together and carefully placed them back into the folder. As they left the trailer, Fitzsimmons, coffee cup in hand, smiled briefly; the others, straight-faced, merely nodded.

Bull, seated at his desk, bottle of vodka and glass handy, stared intensely at a picture on the wall from his military days, when he was a captain, receiving a Medal of Distinguished Combat from Gorbachev himself for service in Afghanistan. He had fought in a losing contest, but had touched basic physical reality in all its soul-wrenching visceral detail. How he felt about himself during that time? He never questioned the right or wrongness of the war itself, that was not his job. He lived from day to day, never knowing when he might take a bullet or get blown up. But how it made him feel, as a man, as a human animal, so sure and confidant; he knew who he was, and would have laughed at anyone who tried to shake that certainty.

But now, with this,..., he got up to lock the door, returned to his seat and poured another. He didn't think he'd be in any shape to attend a town hall meeting even if he ever left the site, which he didn't. He disdained town, and, besides -- science bored him.

ANARCHISTS

Vasily had laid claim to the barstool and wasn't about to lose it to the bar-hopping hordes flowing through. He was waiting for his friends, Nomad and Hub; they had a plan, and they meant to carry it through. Working on the project for two and a half months now, he had amassed a small fortune, for an otherwise broke fisherman, so he could afford his own bottle of vodka at the bar, which he was quickly going through.He had news to tell and was understandably impatient; importance having passed Vasily by at more than one fork on the road of life. This was his chance. That morning they had cordoned off the five spheres last opened, the ones where all the action was. He was not allowed near to perform regular maintenance checks on the scaffolding and electrical outlets -- no nonessential personnel, they said. Bull had given the order; there was no arguing.

Just as Nomad and Hub entered, he spotted a booth emptying of its drunken occupants; with bottle in hand, he went for it and waved them over. Nomad was missing part of his left ear due to a knife fight his greenhorn year of fishing, a long, long time ago, and dressed extremely casually, always the same jeans, tea-shirt, and old wool navy coat. Hub was just that, a two-hundred pound hub of a man; no good on deck but, he could help you fight your way out of a bar if need be. Vasily had left messages all over town that he needed to have a sit-down right away. They saw themselves as anarchists in the old Bolshevic mold, and acted accordingly, or at least what they imagined was the way to act.

Vasily poured a round, it was his moment, he intended to play it up."You guys weren't at the Dig today. Too much last night, huh?"

They just nodded and drank. Vasily roared along, "Well, you missed it. Early this morning I was headed over to P-9 to check things out when I ran into Gregor the Implacable. 'No entry,' he say, 'no come back till we tell you. Go!' What an ignoramous. They have the whole area around spheres P-5 to P-9 tied off, with guards every thirty feet. Something's going down and I think it's about to happen." He poured another round. "If we wait, it'll be too late, I know -- something big is about to happen."