Everything outside was wet, everywhere you looked, running, dripping, soaking, covering the entire world--water. Droplets large and small quivered in the wind like tiny worlds or like an occupying army risen from the flatness. On top of that, he was out of beer, had two cigs left, and no ability to change TV stations. He almost threw the remote across the room, but grabbed himself at the last. He would not give in to fits of anger. Bitching, complaining, yes, but not anger. What he learned from all his reflections would be lost. What went wrong in the past did so because of not letting go of what went wrong before. He knew it in his mind but not his heart, which he pummeled relentlessly, without mercy. He considered suicide; he always considered suicide as a way out.

Frustrated, he donned his poncho and went to his favorite brooding place, a moss-covered tree blown down years ago encircled by tall cedars. The canopy was thick, the rain barely reached him. A few birds huddled nearby. He always admired their toughness, such little birds to winter here. He ruminated over things he hadn't done and some he had, vacillating between regret and self-recrimination. I can't believe I did that was a recurring refrain he'd mumble. He ran through his life as a series of experiences, only those that stood out, that demanded attention to validate his self-loathing, got special attention. They always involved betraying something or other, or someone or other. Himself, at root.

Immobile on the long-dead log while daylight faded, the chill damp worked its way into his joints, stiff from lack of use. Aches and pains followed; he needed to move. He wrenched himself up and, with effort at first, walked down to the swamp. The wind had died to a breeze and the rain to a drizzle. He hadn't noticed, so engrossed as he was in all his failings. The clouds brightened, threatening to reveal blue sky. The swamp water was about as high as it could be, not much chance to drain. The air was muggy, almost warm, and, even though there hadn't been any lightning for days, he distinctly smelled ozone, a faint hint, but there it was. Curiosity drew him into the present. Moving off to his left, he circled the tiny swamp--a pond if not for the reeds and soggy trees growing in it. Halfway around, the pungent smell of ozone sharply increased in intensity. He could taste it.

As he stood there, the heavy clouds parted; what appeared to be a shaft of afternoon sunlight shone directly onto a single spot on the water not twenty-feet in front of him. Instead of feeling gratitude for a rare appearance of the orange orb, something about where it chose to land unnerved him. He pulled out a cigarette and fired it up, taking a long drag. As he studied the light's reflection on the water, what had been an irregular shaft reformed into an ellipse about five feet long on its main axis. Around the edge, the water bubbled. Heat, he thought. What else could do that?

He followed the angled column of light up to the tear in the overcast sky where it shone through, but couldn't see its source. However, he noticed a great deal of turbulence in the clouds surrounding the hole, a churning as though forcibly being repulsed. What he'd assumed was the pale sunlight of winter, now seemed artificially produced; it was too perfect, too coherent, like the beam from a flashlight. Definitely, he was sure, it wasn't the sun.

He stared again at the oval shining on the surface of the grey swamp water. Without looking away, he dropped his smoke to the ground and crushed it out, then backed-up to stand next to a huge fir tree. The hairs on the nape of his neck told him to. As he focused on the spot, mesmerized by the creamy, yellow light, the brackish water of the interior began to bubble as well. If it was heat, he considered, it would spread. The fact that it didn't only encouraged his curiosity. Could it be methane gurgling up? he wondered. But then, why would it be surfacing only within the confines of the light shining on the water?

He picked up a rock with the idea of throwing it into the ellipse, where the light met the water. He had to find out what it was; he couldn't just walk away now. As he was about to lob it, a high-pitched keening riveted his attention. At the limits of his perception at first, the faint sound grew in scale as it reverberated off the water, bathing the entire swamp, precipitating a surge of bubbles everywhere. The rock fell from his hand. Although the swamp appeared to be boiling, he felt no heat, the air remained cool. The screech was like a million metal locusts. It was seamless and continuous and enveloped him completely.

He stood rigid as a pole, transfixed, helpless, unable to think. Suddenly, the pitch jumped in frequency and the ground beneath him hummed, breaking the spell. Curiosity was trumped by the decision that whatever the hell was going on he could do without. It was unnatural, of that he was certain, and potentially deadly. He turned to run but tripped on an exposed root of the huge fir, sending him sprawling. Cracking his head hard on the frozen ground, he lay there fighting for consciousness. The earth rumbled beneath him; the single wavelength of wailing jumped another scale. That was the last thing he remembered before blacking out.

Doctors Hessenbalm and Freiberg had worked out the math when the project was first conceived years ago. Their personalities clashed, but when it came to their professional specialties, they moved together in an intellectual sphere that brought out their best. Hessenbalm understood how fractalized time factors could be isolated from those of space, and Freiberg knew how to manipulate their frequencies to bring forth elementals from a specific time slice--layer of time; in a sense, to re-experience it as the present. They complemented one another's ideas and achieved remarkable results. This latest endeavor was the pinacle of their collaboration.

The year was 2514, time travel had become almost commonplace. Unanticipated incidents did occur in the beginning, unfortunately; some people didn't return from wherever they went. Voyages in time were replete with dangers not then imagined. But that's always been the case with new frontiers; the adventurous and curious were not deterred. In time and with enormous expenditure, the bugs were worked out, the procedure refined to the tiniest detail. The underlying work in the area of sub-quantum, compacted dimensions had been expanded on and supported by all other fields of physics. It was indeed a new frontier, and all the best wanted in.

The two had discovered what they referred to as fossilized temporal structures, fixed moments in time, unique and defining of a period. The geologic time scale of paleontologists distinguishes eons, eras, and periods by defining characteristics and events, especially extinction events, as represented by the fossils of plants, animals, and other organisms in terms of millions of years. The age of mammals, the age of reptiles and dinosaurs, the age of ancient life forms. Field geology divides time into strata--a stratum is a bed or layer of sedimentary rock that is visually distinguishable from adjacent beds or layers. The thickness of any particular stratum is defined by a criterion of certain consistent features, the commonality of its composition. Sixty-four million years ago, the last dinosaur stratum came to an end. Cosmology begins at the big bang and evolves to the age of quarks, age of subatomic particles like protons and neutrons--nucleons, and the age of nucleosynthesis--atoms and molecules.

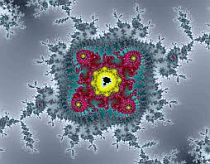

But the layers of time Hessenbalm and Freiberg were interested in were defined by the presence of fixed-time structures and their effects on their surroundings. But not in ordinary spacetime; their focus of inquiry was on fractal dimensions and how these structures--fixed points--formed and why they exist. Measuring detail across a range of scales, they assigned fractal dimensions to classes based on degree of complexity. A layer's duration--thickness or depth--within a given dimension was measured by the persistence and longevity of these zones of changelessness before a transformation to another arrangement or a deeper scale took place. Reasons for this sudden transition were unknown, the field was fairly new; it was the subject of much discussion in the scientific community. However, the two scientists had more important things on their minds.

They'd localized a fixed-time region of irreducible complexity in the recent past that apparently had never experienced transition; it was still viable, in other words. Yet, its existence could not be ascertained after that time--the early part of the twenty-first century, give or take; certainly not in the present. It was as though it disappeared completely, withdrew into the void, instead of rearranging its factors into another fixed-time form as expected. If it did exist in the present, it did so disguised or in other planes of reality, buried deeply nested within the fabric of spacetime, in exponential space, unreachable by any known method of detection. And the probe that found it was unable to determine its origin. Its fractalized temporal displacement was lost in a confluence of other fixed points, a maelstrom of chaotic complexity. It spoke of extravagantly powerful forces at work.

They'd localized a fixed-time region of irreducible complexity in the recent past that apparently had never experienced transition; it was still viable, in other words. Yet, its existence could not be ascertained after that time--the early part of the twenty-first century, give or take; certainly not in the present. It was as though it disappeared completely, withdrew into the void, instead of rearranging its factors into another fixed-time form as expected. If it did exist in the present, it did so disguised or in other planes of reality, buried deeply nested within the fabric of spacetime, in exponential space, unreachable by any known method of detection. And the probe that found it was unable to determine its origin. Its fractalized temporal displacement was lost in a confluence of other fixed points, a maelstrom of chaotic complexity. It spoke of extravagantly powerful forces at work.

With help from an army of other scientists and brilliant engineers, they constructed a rather unique time ship, an upgrade on the current stock. The outer hull was made of bioengineered callasium, an asteroid mineral with the peculiar characterisitcs normally associated with dark matter, alloyed with titanium. The crystal's atomic lattice is fused with microbial organisms; thereby, making it capable of transforming its properties to suit its environment by resonating and organically rearranging composite elements through sound vibrations. The reason for this adaptive shielding was to accelerate passage through layers, reducing friction to a negligible value. It had been discovered that transmission through time causes organics to lose their spatial manifestation, retaining only the underlying sub-quantum features. The ship and crew don't dissolve into the vacuum, however, they still remain corporeal and able to function normally. But from a purely temporal perspective, they are invisible and intangible.

The drive unit for the ship was a fabricated singularity encased in a sub-quark field. It enabled the ship to tunnel through layers of time-slices along their intersecting orthogonal gradient like a hot poker going through a stack of cheese. The ship and all its contents travel through time as a singularity, a mathematical ideal designated as a point, outside normal spacetime where corporeality doesn't exist. In this transit-state, the atomic lattice structure of the hull compresses, eliminating all possible empty spaces between and within atoms. The density of the material of the hull increases in mass approaching the infinite, one click away from that of a black hole. Artificially inducing a cyclic action in each atom by the infusion of oppositely-oriented time elementals allows the hull, and therefore the ship, to enter timelessness. This puts it outside the influence of normal spacetime and the effects of its forces, particle interference, and contours.

After the ship arrives at its destination, it gradually reconstitutes itself--thaws out--adopting the physical-property configuration that surrounds it--all the usual forces, like electromagnetism--rejoining the matter stream and becoming quite solid, eventually. The hull material realigns so as not to fall through the Earth, among other practical, life-sustaining considerations, like the accidental creation of a black hole through implosion. Before then, while in its purely mathematical state as a singularity, the underpinning rules of sub-quantum reality that pre-date the quantum world of ordinary spacetime hold sway.

As the ship transforms--goes through its stages--from mathematical entity outside space and time to physical manifestation in the third dimension, protocols are precisely and strictly regulated from one sub-state to the next, increasing the ship's material presence while simultaneously reducing its mass density, carefully managing the influence of the Higg's boson by scale. Mass is reduced as the hull's atomic structure realigns, and density, which is infinite as a singularity, is decreased. While this process is taking place, temporal displacement adjusts the ship's weight so that it remains constant. When the correct combination is attained, the ship materializes in ordinary spacetime, emerging from fractal timelessness. To depart, the reverse procedure is initiated. It's not a task that can be accomplished in a moment with the flick of a switch or can be rushed.

By modern standards, it was a small ship. Its circular shape, flat bottom, and dome top gave it the appearance of a flying saucer from long ago. About one hundred feet in diameter, quarters would be cramped for the crew and scientists. But it was an expedition, not a vacation. They weren't just on a fact-finding survey, they were on a mission. They anticipated discovering new forces accessible through this fixed point, this fossilized temporal structure. Forces that could be useful for the benefit of all Mankind.

It took three years, a lot of innovative technology, and, of course, many credits, to build.

Regina and Melophile ruled the forest around the swamp, only on another, unseeable plane of existence in another forest altogether. Witches of the highest class, they brooked no nonsense in their domain, nothing unnatural was allowed. They protected the magical community and kept them safe. Word had come that a disturbing field of energy emanating from the surface universe where Roger's swamp was located was encroaching on the anchor. Potentially, if contaminated past a breaking point, it could destablize their worlds, splitting them into countless fragments.

They alerted all the communities of inner space of the threat--the disintegration of the fundamental forces that powered their lives. These forces owed their source and continuous existence to the anchor, the dwelling of the sacred beings, holding together the whole collective of separate magical worlds, like the hub of a wheel. Without it, time would cease and all magic would be lost. The anchor allowed time beyond its border to actively fuse with the beings of all the inner worlds. Although its nature is turned inward; for added protection, it was confined by incantations.

They alerted all the communities of inner space of the threat--the disintegration of the fundamental forces that powered their lives. These forces owed their source and continuous existence to the anchor, the dwelling of the sacred beings, holding together the whole collective of separate magical worlds, like the hub of a wheel. Without it, time would cease and all magic would be lost. The anchor allowed time beyond its border to actively fuse with the beings of all the inner worlds. Although its nature is turned inward; for added protection, it was confined by incantations.

However, a hole in timelessness will overwhelm those bonds and its nature will merge with time. It will spread, bringing to a standstill all domains as it permeates their inner being, creating cracks in time forever apart. The anchor is the many acting as one and must be maintained as such. If its integrity dissolves, magic dies and along with it inner space and the denizens of the magical worlds.

"It cannot be," the witches proclaimed. "We must put an end to whatever is causing this. It cannot be.

Roger came to, rubbing his head. It was pitch dark, nightfall. He stood groggily and braced himself against the tree, trying to collect his wits. The stars were out, it'd cleared up. They gave scant light, but it was something. He pulled his last cigarette out and lit it. In fits and starts, it all came back to him. The recollection. He took a drag and looked in the direction of the marsh. The stumpy trees, tall cattails, and oily brush were gone. In their place stood a solid blackness shaped like a disc. Its top curved from about ten-feet high at the edge to a peak of around twenty feet. As far as he could see, it covered the entire swamp. He thought to approach it, but a strange humming sound coming from its interior caught him up. Call the police, a voice said. And tell them what? he asked the voice. Tell them that an oval-shaped light from somewhere above had shone on one spot of his swamp, then a shrill sound filled the air, coming from nowhere and everywhere, and then his marsh bubbled up all over, and then he knocked himself out on the ground, and when he woke up, a space ship was sitting where his swamp used to be. That could get him stamped a loony and he had enough problems as it was.

It was up to him to investigate. It was his property, after all, and something unwanted was on it. Depite the humming, he walked into the marshy water in his rubber boots up to the ankles. It was right in front of him, this vivid, intense darkness. He lit his lighter and peered hard. But its little light was absorbed at what appeared the surface, making it impossible to tell what it was made of or where exactly its surface began. In spite of being able to hold its shape, he sensed that it was liquid or gaseous. Imagining he saw something move within, he leaned forward. As he did, the lighter burned his thumb; reflex dropped it into the water. Disgusted, and still feeling the pain from his banged head, he reached forward to touch where the surface blackness seemed to be. He felt nothing on his fingertips. He plunged his hand in as though it was water; it disappeared. Mystified, he put his whole arm in up to the shoulder; it too vanished from sight.

He splashed back a few feet to reconsider. The emptiness was neither warm nor cold, it had no temperature he could discern. But its reality, now that his eyes had adjusted to the starlight, was plainly visible. If there's nothing solid in front of me, then what am I looking at? And what keeps the birds and squirrels and everything else from going in? To where? The thought of walking into it entered his mind. Would I get lost in utter darkness, unable to find my way out? he wondered. Or, would I be walking deeper into the water? And assuming the water isn't too deep, if I were to walk straight ahead, would I end up on the other side of what used to be my swamp? Is that all there is? This black gaseous nothing? An illusion? And my marsh is still here?

He wished that to be the case and that this was just an extraordinary incident of a marsh-gas configuration. He reached for a cigarette but the pack was empty. Besides, he remembered, his lighter was in the drink. Frustrated, he forced himself to think: the bubbling could point to that, to gas. But what about the disappearing arm trick? And how come the trees and everything else that grows here seem to be gone? And the shrieking, and the humming, and the ground vibrating and rumbling? And all that jazz. No, he decided, this is no illusion caused by anything natural.

His mind, once inquisitive about the world before it turned against him, leapt into his imagination. When he was younger, he'd read tons of science-fiction and real-world science books--popularizers--and magazines, intrigued by the possibilities and ideas. During that time, his thoughts and understanding tracked along those lines, far-fetched though they sometimes were, rather comfortably. Those were good times, he suddenly recalled. A period in his life when he enjoyed every moment and wanted the whole world to enjoy it with him. He believed that life was a celebration of itself; that we are here to know and experience in the name of the universe; that the possibilites of other planes of existence were self-evident. All these thoughts flooded back in like an avalanche of bits and pieces of a completely different person. And as they did, that abused and abandoned part of his mind worked to remember, like a rusty machine coming to life. And not only to remember, but to revitalize and be what it once was. To deconstruct concepts and synthesize ideas. To think.

He considered: if not an illusion caused by explainable phenomena, it may not be physically present. What can be seen is only this hazy residue of its actual presence out of phase with the ordinary world. A solid sensation coursed his chest. He remebered now how that feeling used to accompany an intuitive jump. As though he were merely opening himself up to what is, and the ideas emerged unbidden and unexpected. He was no scientist, but, regardless, he recognized an unnatural event when he saw one. It begged for explanation, but at present, he had none. More experimentation was in order, he reflected, firm in his determination. He decided to go back to his house and get a flashlight and whatever else came to mind. Familiar as he was with the lay of his forest, he had little trouble in the bright starlight finding the path on the other side of his former swamp.

Hessenbalm and Freiberg busied themselves setting up various experiments. Having succeeded at transporting to this particular point in time and at this particular place without mishap, they went about their work with exuberance. They had chosen now and here from a dozen other prospective locations for its special nature. Their interest was in fixed points in time. A probe, designed to search out fixed, or recurring, points as it dove down through slices of time had been drawn to it, an oasis in the desert. Like ice-core samples from the Antarctic revealing strata profiles, anomolous perturbations appeared at this site indicating novel forces at work, forces unknown that had somehow intermingled to form an integrated cluster, an amalgam, animating unfamiliar planes of reality.

Their plan was to attempt to come in contact with this conglomerate field, to ascertain why it exists, and to test the nature of the combine as a whole and also break it apart to study its component structures. It was a moment fixed in time where nothing changed. Ordinarily, time transforms reality, orchestrated by forces, into the next thing. They wanted to know why spatial rearrangement, development, evolution, and normal activity were not happening here. It should not be behaving as it is.

Hessenbalm's paper on Topological vs. Geometric Time Infinitesimals [subtitle: the nature of internal and external time] explained in detail their rationale for focusing on fixed points. Excerpts follow:

There are two types of time differing by their arrangement on mutually embedded scales. Ordinary time effects things in space, the natural forces that govern our universe regulate and organize occurrences and events. Extraordinary--or meta--time affects only space itslef, the context, the frame of reference, as it evolves independently of what occupies it. Time drives Space; Space is derived from Time. Time is all there is at root. Space is the effect, the result, the consequence of consciousness passing through the prism of time. An alternate idea for consciousness could be as the generator of vacuum energy--zero-point energy--whatever that may be. Or, could time be manifest as that vacuum energy operating within space through all its dimensions, expanded and compacted?

In mathematics, a fixed point is one that maps to itself. So, if you have a fossilized temporal structure behaving this way, what does it mean? The spatial change keeps repeating or cycling back onto itself in an infinitesimal loop; thereby, causing space per se, or the spatial elementals conceived independently, to remain constrained and unchanged--unchangeable.

They had a crew of six, all veteran time travelers and engineers specialized in various technical areas. Strange forces held sway here and they meant to find out what they were.

Regina and Melophile had sent messages to the elevated shamans and leaders of the magical community informing them of circumstances and proclaiming an emergency meeting. The Great Hall of Mirrors on their forest compound was filled with all manner of creatures, from the very large and none too bright to the extremely tiny and erudite. Conversation was agitated, confusing, and loud as they waited for the two witches to arrive. Everyone had an opinion, but the general consensus, if a vote were taken, was to use force, all the magic they could jointly muster. Couriers dispatched had briefed them only on the larger picture, the details had yet to be explained.

They were aware that the area under discussion concerned their region's anchor, one of countless others spread thoughout the universe. It stabilized the many and varied dimensions of the community by giving them a touchstone outside of space against which to calibrate subtle time-dependent translations. To travel from one place to another, for instance, or from one world to the next, took a considerable amount of concentration. Timing is everything. If frequencies wavered at random, who knows where one might end up? More importantly, anchors were necessary as coherent and reliable resonators in order to manipulate available and accessible forces--perform magic. One channeled forces; one did not use them from without, as objects to be controlled. They must be attuned to the being as to his realm. And this cannot be done without the continuous integrity of the grounding anchors.

The witches appeared out of thin air and stood at the head of the long table. Melophile, the youngest, smiled briefly and sat down. A cup of wine immediately appeared in her hand. Regina wasted no time. "We live in shards of dimensions within those of ordinary space, boring holes and tunnels in its interior, and between dimensions, creating planes of reality. Countless frequencies seeding the essence of time delicately in concert with one another make this possible. If this precise balance is upset, the entire network of magical worlds, separate and independent now, will collapse. We rely on one another for our very existence.

"If that space is corrupted and violated, its constraints, its bounding spells, will lose their power and dissolve into the void whence they came. At first, we'll notice the fluctuating instability as an intermittance in the effectiveness of our abilities and gifts. But that period will not last long. That time that stands still will spread, permeate the domains, circle back in on itself everywhere until time stops everywhere."

The room erupted in alarm and outrage. Quite a few of the participants blinked out, reemerging on the other side of the room. An automatic reflex that was also a test to see if they still could. Now they had some understanding as to what they were up against, what threatened their very lives.

She waved them into silence, it wasn't easy. "We must stop this. Something from another place and time has appeared there for reasons unknown. From that plane of existence that dwells on the surface of the universe. We have felt its internal vibrations and recognize the telltale signs. Its mere presence has caused a time shift, but one that, so far, affects only its internal space. My sister and I have increased the power of the binding spells to compensate for the bridging of the threshold, but they will not hold up if the sacred beings that animate our worlds are overly disturbed or forced to cease movement. They revolve around themselves. They are drawn to themselves, necessarily and neverendingly, as the self seeks out its meaning."

She waved them into silence, it wasn't easy. "We must stop this. Something from another place and time has appeared there for reasons unknown. From that plane of existence that dwells on the surface of the universe. We have felt its internal vibrations and recognize the telltale signs. Its mere presence has caused a time shift, but one that, so far, affects only its internal space. My sister and I have increased the power of the binding spells to compensate for the bridging of the threshold, but they will not hold up if the sacred beings that animate our worlds are overly disturbed or forced to cease movement. They revolve around themselves. They are drawn to themselves, necessarily and neverendingly, as the self seeks out its meaning."

She spread her arms and spoke into the minds and hearts of all present. "They stand still and yet move; remain static, yet are continuously in motion. In the act of becoming, they return to the source, to the timeless now, to the essence that gave them birth. They are movement and will made manifest. They are mindful of our worlds even as they give them life. They are absorbed in a single instant, forever engraved in space itself, as when the universe was first created. Their spirtual identity cannot be knowable or even imagined by these intruders. And yes, my friends, there are agents at work here, it is not an accident of nature that is taking place."

She drank from a cup to fuel her words and set fury on its course. "A vessel from the future has materialized within the confines of the anchor. It brings with it a time dimension that vies with the sacred beings and conflicts with the present. Magic can't penetrate the barrier of the anchor. Though it be its cause and reason, it has no power within. Inner space exists, we exist and possess the gifts and powers we have as long as the anchor remains separate and undisturbed. We cannot interfere with what gives us the power to do so. So, as much as we would like to send them back whence they came, we cannot.

"We can wait and see what they do," she said nonchalantly. "Perhaps nothing." The crowd of concerned, otherworldy citizens boomed their disapproval, shouting no in several languages, and banging cups and fists, some quite huge, on the hard wood table. Leaning forward to meet their protest, she roared back, "But they've chosen that spot where the anchor lies for a reason. It is no coincidence. So they intend to do something. To violate the sacred beings who dwell therein. They who keep all our worlds alive. We must not only stop them but also insure they never come back. That is why we are here tonight. We need to find their weaknesses, to understand what they're capable of. We rely on you to use your gifts to channel back to the source, to tell it what is happening, let it know of the threat, and ask it for help. To tell us what we can do. All of us together must enter that original mind. To commune with it, to mingle with its thoughts.

"For the survival of inner space and all its inhabitants."

A roar of defiance went up from the gathering, rumbling the rafters. The chord was struck. Regina, however, was not pleased with the helplessness of their situation. Their magic was of little use. She could enter the minds and know the desires of the humans in the ship, to try to discover what they intended to do. But that was all.

Roger returned with a 6-volt flashlight, his twelve-gauge pump, and a piece of one-inch plastic tubing about 6-feet long. It was still there, he hadn't imagined it. However, the inky contours seemed to be more enhanced, sketched in. He pushed the tube in to its length, it vanished from sight and touched nothing. Exasperated, throwing caution to the wind, he threw the tube to the ground, and, with arms stretched before him, stepped into it. As soon as he passed the boundary of its contours, the sound of water underfoot ceased. In fact, he could sense nothing. And not only could he not see his body, he couldn't feel it either. His hands touched emptiness. No head, no trunk, no legs. He backed out, alarmed, and stood near the bank. He'd rolled a cigarette from butts when home and grabbed a pack of matches. Now was the time to smoke it.

As he stood staring at the apparition before him, the humming sound he heard before started up again, only the tone was deeper. He turned his flash off and waited. The blackness brightened from deep within. Not from the interior of the ship, but from itself, everywhere at once. Gradually, it filled in, thickened, built-up, as though painted with a gigantic brush over and over again. He could now see an unmistakable spaceship sitting on his swamp. Instinctively, he shined the flash on it. Dull moon white, its hull was smooth to the eye. He didn't hesitate. He stepped forward to touch it to reassure himself that it was actually there. Its surface was warm and elastic, like soft rubber, but felt like skin. Only a centimeter or two in, he hit what felt like hard metal.

Impatient to do something, he circled the ship, counting off distance, three feet to a stride. Examining the hull as he went, he could see no distinguishing features or protuberances indicating sensors of some kind, no seams or cracks where a door might be. Back at his starting point, he counted just over three hundred feet. Gathering such superficial information didn't lead him to imagine he was in control of the situation; to think so would be absurd. But it made him feel less afraid and more resolute. However, somebody was, he knew, and whether or not he wanted to meet that somebody, or some thing, was another matter.

He stood in the damp on the bank holding his shotgun and flash, wondering what to do next. He could call the police and tell them he had intruders somewhere on the property, tresspassers, to get them to come out here. Maybe they would, maybe they wouldn't; in these parts, people usually dealt with tresspassers themselves. But then, he'd have to go back to the house, leave the ship. Would it still be here when he came back or vanish like it appeared? It didn't look like it was going anywhere and his presence certainly had nothing to do with it either way.

Indecisiveness gnawing at his gut, too overwhelmed to think straight, a creature only a few inches tall flew to a stop right in front of his face. A sphere of light around it glowed brightly; he could see on its tiny face a definite smile. Shocked out of his skin, he recoiled backwards like he'd been punched, slipping on the mud and falling on his ass. His flash and shotgun were left behind. Wings vibrating manically, the diminutive being hovered over him and, in a high-pitched yet sympathetic voice, said, "Oh, I'm so sorry. Are you all right?"

He had indeed fallen down the rabbit hole. Concerned for his sanity, he lay still, finding odd comfort in the thought that the spaceship and this creature must somehow be related. It was all he could do to suppress fear and panic. His chest squeezed tight, he knew the signs. He felt it on the sea when fishing through stormy weather. Then, he would turn that threat into its direction, fueling his blood with purpose. Giving in was the end of the road. He fought to be open, to accept what was happening. To do otherwise would be to flounder for an explanation that simply wasn't available. Mythology and legends have a note of truth at their base, he reflected, they're not all make-believe. As good a rationalization as any.

"Are you all right, Roger?" the creature repeated. Not hearing an answer, she said slowly, as though to a child, "My name is Fralene." She landed on a rock near his head, now turned sideways to see her. Her wings ceased their frantic vibrating. He could see now her human appearance, with long hair and clothing that shimmered on its own. "Oh, do stand. And why look so aghast? Don't be afraid; I won't hurt you," she giggled.

Softening to the moment abruptly, surprisingly, as though the most normal thing in the world was happening, he sat up and asked, "How do you know my name, little one?"

"Fralene," she corrected him stiffly, pulling herself up to her full three inches. "We've always been aware of your presence and have felt sorry for your malady of sadness. You won't let yourself be happy. But that's another story for another time," she said dismissivley, shaking her head. Facing the ship, she said, "We've watched you deal with the blackness, and now, this vessel, if so it be."

Roger continued to sit. Fascinated, he found himself accepting her as real, and in that moment, his world forever changed. It was only polite to continue sitting, he thought. And listen to what she had to say.

"But now, we need your help."

"Who does?" he asked.

"Why, the entire magical community, all of us, and the universe needs your help too."

"The universe?"

"Yes. Come. It will all be explained by Regina."

"Regina? Who..."

"She is the head witch and ruler of the many worlds, for the good of us all. The forest is her private domain."

"The forest? But I live here and I've never seen her."

"Oh no," Fralene laughed, cupping her hands over her mouth. "Not this forest." She flew up over his head, scooped some golden dust from a pouch at her hip and let it sprinkle down. "This forest."

In the blinking of an eye, he found himself surrounded by lush greenery and flowers of every color and combination thereof. Inquisitive, they all leaned towards him, sitting on the sandy beach of a good-size pond. Lilly pads dotted its surface and on some of them he swore he could see small houses built of sticks and leaves. The air was warm and tasted of lillacs and rich, black dirt. Fralene flew in front of his face again and said, "Well, silly, get up. I'll lead the way."

She flew, he walked behind her, taking off his rain poncho and rolling up his sleeves. The sun shining through the canopy where it could soothed his face and arms like a soft caress. Insects that looked like bees but with larger eyes swarmed about him. They talked to one another, it seemed to Roger, nodding and gesturing as they went. Fralene turned and scolded, "Leave him alone now, he's new in these woods."

Immediately, they dispersed, grumbling noticeably. Creatures that resembled squirrels stood on two legs on branches to ogle as he passed. Birds raced ahead of them through the trees announcing their coming. He heard running through the dense brush but saw nothing, only the sound of footfalls, some light, a few very heavy. He was about to ask how much further, when the forest atmosphere abruptly shifted into a more garden-like appearance. The trees thinned out and rows of well-behaved flowers stood proud, attending to the bees and butterflies.

A huge, three-story house sat in the middle of several others less conspicuous but no less ornate. Extensions and porches at every corner, like a living thing growing out at every available angle. Fralene led him to a tall double-door etched with the most improbable collection of animals. It opened by itself on their approach, smells and fragrances wafted out, none of which could he put his finger on. They proceeded down a long hall made of trees arranged in rows. The floor rug was moodily changing from deep red to auburn and back again, breathing texture into the air. The walls were adorned with paintings that seemed to come alive as Roger passed, acting out whatever scene they depicted.

They followed the aroma of scented mixtures as it thickened. Turning a corner, they entered a massive hall, from its ceiling of huge wood beams crisscrossing its length two-stories above hung chandeliers of crystal; they deflected light from every angle. A hundred feet long, a wide wooden table surrounded by high-backed, cushioned chairs ran most of its length. On it were bowls and plates of succulent dishes and flagons of dark, red wine. The combined flavors overwhelmed his senses. The floor was covered with a tapestry of indescribable creatures and tiny figures that shuned away as he stepped down. The paintings were as large as the mirrors they interspersed. One depicted a battle scene with winged horses and dragons. He looked away at some food on the table and then back again; the scene had changed to one of a river running through a vast countryside with mountains in the background. As he passed mirrors, he glanced at his reflection, only to see his eyes looking curiously back at him. At the far end of the table sat Regina and Melophile, expressionless.

No one else was present except for ferret-looking animals wearing aprons and clearing the table of empty plates. He flopped his poncho over the back of a chair. He was exhausted, bewildered, and losing his memory of what passed for normalcy, something he now knew needed serious updating. Regina smiled and invited him to sit next to her. Fralene came to rest on the edge of a plate beside him, dipping a finger into a bluish sauce.

"You must be famished. Please, eat and drink. We'll talk later." A ferret put a plate and utensils on the table before him and produced a flagon of wine. He wasted no time, he couldn't remember when he ate last or what it was. He had to pause at his first mouthful. Never had he tasted anything so delicious or satisfying. He ate slowly to savor every flavor and drank the ruby wine, its texture meshing perfectly with his tongue, its fragrance danced in his head.

He had time to think, to try to make sense of it all. He watched the ferrets preparing for the next feast. They moved smoothly, effortlessly, without speaking to one another. The chandeliers were more than just opalescent crystal. He could see now they sparkled from within, breathing light into the vast hall. The figures on the tapestry changed shape as he stared; they were each all creatures in one. His hand rubbed the table, it couldn't be smoother and yet he could feel its grain rise and fall as his hand swept by.

Satiated, he sat back with the cup of wine in his hand and took in the whole scene. He was flabbergasted, to say the least. He didn't even want to try to remember what he'd been doing that morning. He couldn't, even if he did want to. His mind at present no longer ran in those currents; he was in a completely different sea with its own rules and he'd better get used to it.

Regina had been watching him as he ate, Melophile had been busy playing with a small, furry creature on her lap. They didn't look to Roger like witches who wasted much time stirring a cauldron. No pointy hats; no deep, angry, sinister facial lines; no warts. In fact, they were quite beautiful even as their ages were undefinable. Dressed in leggings of vivid black and overshirts of simple embroidered linen, red for Regina and sky blue for Melophile, wearing boots of thick, softened bark, Regina's black, curly hair hung down to her waste, Melophile's was blonde and braided. She had a coyishness about her that Roger felt drawn to. Something told him it was intentional.

Regina finally spoke. "We invited you here, Roger, because we need your help."

Roger skipped over the help part, what could he do to possibly help magical people? But he asked, "Here. This is a dimension, a plane of existence, I'm guessing. Correct me if I'm wrong. So, how am I able to be here?"

"You are able to be in our world because the forces that govern it include those of yours, they are far more complex. Plus," she smiled, "they welcome you, which is a good sign." She picked up steam where she left off. "Beings from the future now dwell where your swamp used to be."

"Beings from the future?" he asked incredulously.

"He does that a lot," interjected Fralene.

"Yes. Far into your future, they reek of it. We know what they're trying to do from a magical perspective. Our worlds, of which there are many, depend for their continued existence on the stability of this zone of changelessness. It lies," she paused, "beneath the world you know. A meeting ground of continuous renewal where time turns in on itself, identifies with itself. Our worlds rely on this neverending state for their realities and the forces that permeate them. Your space and time are in peril as well. So you see, it is of the utmost importance that they not be allowed to render incoherent that anchor. They are of future time and do not understand what they're doing. They've learned how to find the anchors in space by traveling through time. They believe these are the sources of great power concealing forces of nature never before discovered. Which is partly correct. However, to unravel them would undermine the stability they maintain for inner space. The structure would not hold."

"So that is a ship and there are people in it. You've met them?" Roger asked.

"Only through mediums unknown to them. We see their minds, their thoughts, and feel their desires. From their point of view, this time is dead. Somehow, they found an anchor where time never changes into the next moment. It is self-contained, a moment unto itself. They want to make time stop cycling and proceed naturally according to the surface laws they're familiar with. They think that by doing so, the forces they detect--magical forces they could never hope to ensnare or understand--will issue forth into the rest of the universe, free at last, to be used by them. But they have it backwards."

"Whoa, your majesty. I'm sorry but I have no idea what you're talking about. Truly. You lost me back there with the zone of changelessness and time turning in on itself. And, my universe is in peril? If you could start at the beginning, please, you know, like a primer for dummies, I'd appreciate it."

Regina stared. She stood and walked around behind him. Placing her hands on his temples, she mumbled words in an ancient tongue. Roger felt a pang of discomfort, followed by a sensation of drifting on clouds. "What did you do?" he asked, startled by the changes in the surroundings. The hall took on a watery appearance, objects blended into one another, then abruptly reformed on multiple dimensions at once. The effect lasted a few seconds, then everything returned to what they'd been.

"I'm preparing you to see ideas for their own sake. Thoughts without names." Her voice had changed; at least, Roger heard it differently. He didn't think about what she was saying, as he usually would do when listening to someone, the words went directly into his now empty and open mind, forming an image, a language of its own. She walked to the wall behind her chair and waved her hand, a section of it turned white. Using her index finger from a distance, she drew three circles equidistant from one another and lines connecting them. "Timelessness, where space meets time," she pointed to the circles, "are anchors spread throughout the universe." She drew a point at the centers of the circles and from it, swirls of increasing diameter curved out to the cicumference, the boundary, she explained, interfacing the anchor and normal spacetime. With a wave of her hand, the spirals compressed to include the entire interior of the circles. "This is inner space, over-simplified abstractly, of course."

These are not the witches of movies I've seen, thought Roger, fascinated, as his mind let go of ingrained misconceptions and prejudices, like leaves blowing down the street.

"Regions of space depend on these circles, what they represent. Together, they form a web of constantcy for space and time to play out. They regulate the rules of both outer and inner space, where we reside. They act as intermediaries, maintaining a constant balance and symmetry. Sacred beings dwell therein. Beings, who by their very nature and dimensions, create all planes of reality. And by so doing, the possibility for life on them as well. Inner space is the home of the many worlds we occupy. They are," she paused again, "contained within surface space, unseen and unknown."

"Like wormwood found on the beach," muttered Roger.

"The anchors are composed of separate beings that, on all planes and dimensions, never change their identities. They reinforce themselves as they return to their source. Each of our worlds is mirrored in the patterns created by their interactions with others. And, there are as many of these patterns as there are dimensions of inner and outer space. The more complex, the more difficult it is to continuously recreate, but the more intricate the balance, the more powerful the forces. Without them, inner space, with its complexities and intertwined relationships, would collapse. And not just in one world; we are all interconnected. What happens to one happens to all. What keeps the many worlds running smoothly and without conflict of any sort are the anchors of timelessness, they form hubs of convergence and constantcy throughout vast regions of the universe. They join inner and outer space at the origins of both, where timelessness gives birth to time and space. Without them, there would be disintegration, chaos, and dissolution, leading to the collapse of inner space and the end of magic and all its people. The time essence must continue to return to itself alone."

She returned to her chair and drank some wine. "The anchor for this region lies in a time-shifted space where your swamp used to be. And now, there's a ship of men there determined to upset the apple cart."

The apple cart, thought Roger. She did see into my mind, what else did she borrow, I wonder? "Well, I get the gist of it, I think. It seems what needs to be done is to stop these guys from destablizing that anchor, however they plan on doing it. Trying to unravel time's constant recurrence. Am I am in the ballpark?"

"Yes, I believe so," Regina nodded, a glint of respect in her clear, black eyes.

Melophile said, casually, "It's only a matter of time before they succeed," as though any more urgency needed to be added.

"But how do you know they can?" asked Roger, warming to the discussion as though he swam in such currents all his life.

"We don't," said Regina flatly. "We don't know if they have the knowledge or the means. Knowing what they desire to do doesn't mean they have the ability. If they don't, fine, well, and good. However, the very fact that they are aware of the time essence and its significance tells me they might be close to the secret. We've seen thoughts and ideas in their minds that are mere words, labels. We have to find out what their practical meaning is, what they point to."

"They need to do one of two things, as I see it," began Roger. "Induce time in the anchor, cause it to generate time as it's done for the region of ordinary space, thereby, ending the time essence's job as creator of the dimensions that compose inner space, or, eliminate the boundary that contains the time essence, cause it to spread timelessness throughout space. Either way, what they'll accomplish is the collapse of inner space and the destabilizing of the entire region. Its interior structure will be compromised."

Surprised, almost stunned, Regina leaned forward to study this new creature. Melophile shot him a piercing glance as though noticing him for the first time. Fralene fluttered about, unsure what to feel. Even the ferrets stoically going about their job stopped to glance his way.

"But, I still don't see what help I can be. You're far more capable than I. You and your sister. I examined the hull; there's no way to get in to talk to these people, explain to them what they're actually trying to do. I suppose I could knock on the hull; I didn't think of that. They don't have the understanding of the universe you do. How it works. But if you could talk to them, perhaps you could convince them."

"A witch discussing the physics of the universe with people from the future," spelled out Regina. "Assuming that were to take place, do you honestly believe that after all the trouble they've no doubt been through to get here on the mission to discover new forces that a talk with me would convince them of the error of their ways? Roger? Especially after I explain to them that I'm from another plane of existence that dwells within space itself? If they believed I was who I said I was, it would be more of an incentive, they'd redouble their efforts. I would be bona fide living proof that forces of alternate dimensions actually existed and were therefore accessible. The part about destabilizing the universe would be seen as a deception or an outrageous misunderstanding by an ignorant dweller of the netherworlds."

"That's awfully cynical, your highness. They may be more amenable than you think. They are humans, after all."

"Exactly my point. We've looked into their minds and desires. I've seen the blind passion that drives them. Their purpose isn't soley scientific, it's personal. No, even if possible, there must be some other way. Which, Roger, is where you come in."

Even though Hessenbalm and Freiberg had collaborated on projects for years, their personal chemistry had precluded the formation of a genuine friendship. Nonetheless, academically and professionally they shared the same objectives, zealously pursued. In spite of this bond, their conversations were somewhat less than effusive.

They were having a late dinner; the day had been less than profitable. Gliches kept turning up in the software. They had a state-of-the-art DNA-gel computer running artifical intelligence designed specifically for this project. But still, as always, it needed to be tweaked when on site.

"It's the nonlinearity in the fractal pattern that is the genesis of its supporting forces," stated Hessenbalm. An ongoing argument between them was about to begin.

"The matrix is embedded in the fixed-time composite," replied Freiberg. "It determines the geometric arrangement that generates the particular forces for each dimensional reality as factors, the overall complex pattern it adopts. Each and every one of the countless temporal units is stamped with the identity of self-recurrence."

"But you're ignoring the global topological self. The nonlinearity is the whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. It is the global integrative effect, an attractor. If we can disrupt the morphogenetic field, the nonlinearity that holds it all together and regulates position in each fractal network--what organizes the elementals--would lose coherence. They'd spread and begin to evolve change in our ordinary spacetime, and by so doing, release the forces that are bound up in the matrix, unfixing time."

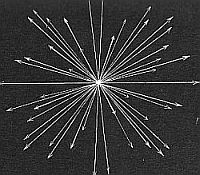

"We both know that quantum time-elementals are the progenitors of linear time," said Freiberg, his tone, one of a confidant. "Their arrow of orientation aligns with spatial elementals orthogonally as they permeate the universe. But what we have in the matrix are wavefunctions of elementals pointing in every possible direction; somehow, beyond our computer's capacity to calculate, they maintain a dynamic balance. Well, that being the case, we can't just flood the entire matrix with randomly-oriented elementals, hoping that they'll accidentally line up in just the right way to counter those of the matrix. That's impossible. We need to take another approach. We must find the basis vectors that generate and define all the others. Each basic time infinitesimal is oriented to support a different fractal dimension. It stamps this identity onto countless others forming a factor. Combined, they form separate networks by affinity and reinforce the entire meta-network of sets of forces--the matrix--through their interaction. The basis contains vortices of primal energy generating the whole of the complex. We need to find them, localize them. Then, reversing their orientation will work its way through all the separate factors by induction, breaking their hold and releasing linear time."

"We don't know that for certain," countered Hessenbalm. "Assuming we can find what must be an enormous set, reversing each individual orientation might result in total nullification of all forces in the matrix. Like matter and antimatter coming together, they might simply cease to exist. Dissolve into the backbone of timelessness. Beyond our reach."

"I don't believe so," said Freiberg, digging in his heels. "The basis vectors of the matrix are similar in prominence and in function to regulatory genes by inducing self-organized activty in the others. They dictate expression--the factors of networks. As such, they must stand out in some definable, measurable way. I believe--if we can get that damn computer to work right--that a survey, on that level, of the entire zone will reveal them. Then we can focus on how best to disrupt their continuous looping."

"What're you talking about? They're not similar. Regulatory genes don't stamp their signature onto the working genes, they don't induce an orientation. They initiate action by something otherwise independent. Our networks are not so."

"I know. The analogy isn't perfect. But they share the same quality of prominence, of hierarchical rank. They must stand out some way."

"That we have yet to determine."

"We need to conduct a survey, I'm telling you," insisted Freiberg. "I'm certain they exist."

"When the computer decides to stop being so temperamental, perhaps we can do that. In the meantime, let's consider what we can do. If we could induce an avalanche in the criticality, that would disrupt the field, create a discontinuity. That's all we need. That moment of transition before it rearranges itself. As the matrix falls from the state of disequilibrium, it will disentangle from the individual networks. Their identities will be forfeit. Then, a flood of random elementals will cause further disarray, past the breaking point, pushing them out of the virtual and over the edge into linear time, freeing the forces they possess."

"And how would we go about that with the machine not working and the computer misbehaving, dear professor?"

They volleyed back and forth until the wine ran out; they were saving it to celebrate, but needed it now. They hardly ever drank alcohol when on a project together, but they were frustrated. Normally methodical in detail, something about this place quickened their drive. A sense of urgency filled the air. On top of that, impatience and irritation at the equipment interfered with their usually placid thought processes. The mechanism channeling the singularity drive that produced time elementals to specifications had yet to operate according to program. Orientations and fractal dimensionality were random. Their best engineers worked on it, replacing parts and running simulations.

They concentrated on the ship's computer. The modern DNA-gel computers were capable of growing synaptic configurations, synthesizing common denominators, and creating new pathways--stable neural nets--in the substrate that best fit the software environment; thereby, allowing for ordered expansion of the genetic material, increasing exponentially their capacity. They worked continuously in a state of flux far-from-equilibrium, nonlinear dynamical systems on the brink of new arrangements; they were agile, adaptable, and multi-tiered. Guided by an artifical intelligence with an almost unlimited capacity to learn and deduce inferences, they saw no reason why it shouldn't work flawlessly. And yet.

Inherently, normal spacial and temporal elementals possessed the property of orientation, much like the spin of an electron, without which there would be no linear time and no spatial extension for it to play out. Based on that premise, instrumentation initially designed to detect motion in the virtual world of the vacuum had been reconfigured for oriented--cause and effect--time elementals. This data was sent directly to the master computer. At this stage in the project, however, it had yet to occur to them that the computer's problem with regard to determining orientation might just be that they had none. They knew this option existed, it was their original conjecture, yet they could not break through to its physical implication, its meaning and significance. The evidence was staring them in the face, but because of its ambiguity, they chose to conclude that the computer couldn't find any that stood out as preferential owing to the sheer number of orientations, each with a different direction.

The possibility that they had no orientation was incomprehensible to imagine. They felt if they looked deeply enough or at the proper fractal scale, they could detect a preferred origin for the looping. They'd made a fatal assumption at the outset that was more hope than science and brought into question their understanding of what they were attempting.

In spite of the shortcomings of this model, they continued to conduct their investigation through a quantum lens. They convinced themselves that the act of observation would issue forth a preferred orientation--the collapse of the wavefunction--and in that nano-instant, they could direct an inverted elemental precisely aligned so as to neutralize its effect. Thereby, breaking its self-looping bond and, in the process, setting free linear time. This, in trun, would induce, through entanglement, a cascade of asymmetry--a contagion--and release the alien forces pent up in the collective, the matrix. Theirs for the taking.

But, based on data, the elementals appeared to be immune to observation; indeed, they showed no reaction whatsoever. They could be seen but not touched as though enclosed by a sub-quantum membrane or were nothing more than reflections. Incredible as this was, they had no choice but to jettison the quantum model as non-applicable. If the detectable elementals possessed no quantum reality and had no discernable orientation, they had to recognize that they were dealing with a natural phenomenon that behaved in a manner outside the realm of what was currently known in the field of space- and time-elemental physics.

Ironically, that's where they came in. Their conception of fixed-time elementals was proving to be correct; however, they still couldn't accept it. They lacked faith in their own insight because they shied away from its implication about how the universe was constructed. If that was the case, what would be the purpose of these fossilized temporal structures, these zones of fixed, self-looping time elementals? It refuted the basic tenets of the topology of the cosmos as presently understood. And, despite their high opinion of themselves, they didn't feel up to the challenge of reframing the entire universe.

Einstein's equations said the universe was expanding, yet he rejected his cosmological constant, later proven to be right and relabeled dark energy. He felt comfortable with a static universe, he wanted it to remain that way despite what the math said, math that was otherwise correct in its description and rewrote cosmology. And if Einstein wasn't ready to accept the implications of his own revolutionary insights, what can we expect from Hessenbalm and Freiberg?

Einstein's equations said the universe was expanding, yet he rejected his cosmological constant, later proven to be right and relabeled dark energy. He felt comfortable with a static universe, he wanted it to remain that way despite what the math said, math that was otherwise correct in its description and rewrote cosmology. And if Einstein wasn't ready to accept the implications of his own revolutionary insights, what can we expect from Hessenbalm and Freiberg?

At the outset, they'd chosen to conceive of a zero-dimensional point as the intersection of an infinite number of lines, with no real independent existence of its own. Transferring this idea to the material realm proved a failure. Therefore, they grudgingly abandoned the omnidirectional idea as being untenable and took the opposite tack.

However, their conception of continuous motion, as a measurable event, without direction was limited to being purely mathematical--a normal vector of zero length. They were unable to make the crossover. Even though they'd written the book on fixed-time elementals, had brought the idea to the fore, it was a blind spot they couldn't resolve. Mapping the mathematical idea to its physical counterpart was precisely what they had already proposed was the case. To do so now, however, in the midst of its reality, to follow their intuition as they did when first imagining such creations, undermined the fundamental premise on which this project found justification and the only hope for success: If it's a fixed point in time, it loops back onto itself, and therefore its motion must begin its trajectory in a particular direction. Clearly, they weren't operating as scientists on the verge of discovering the origin of time, they were prospectors, in denial of what they intellectually believed. Fixed points in time held promise of untold riches, yet they couldn't deliver.

In the early stages of this project, they worked out their methodology on paper, so to speak. This was the first field test. It considered its basic tenet--the nature of an actual fixed point in time--as an unknown; otherwise, they had no expectation of success and so had no reason to take the trip. They'd expoused what the math told them to the rest of the scientific community and to the world, but they chose to ignore it themselves, a serious mistake in their reasoning. Refusal to see this as wish fulfillment only, and not the result of painstaking analysis, was based on an unconscious contradiction in their thinking. They harbored two opposing notions side-by-side without noticing.

In Hessenbalm's treatise on infinitesimals, in fact, he writes, 'All temporal elementals in ordinay spacetime have a causal orientation; fixed-time elementals do not and that's what distinguishes them for further study.' However, privately, he believed, as did Freiberg, that the vector wasn't exactly zero length, that an orientation did exist as an infinitesimal, difficult to pinpoint. Excessively stubborn as this position appears, unexpected discoveries have happened in science all through its history. In the early 21st century, for instance, it was found that the neutrino, in spite of its ghost-like properties, did indeed have mass, negligible as it is.

In Hessenbalm's treatise on infinitesimals, in fact, he writes, 'All temporal elementals in ordinay spacetime have a causal orientation; fixed-time elementals do not and that's what distinguishes them for further study.' However, privately, he believed, as did Freiberg, that the vector wasn't exactly zero length, that an orientation did exist as an infinitesimal, difficult to pinpoint. Excessively stubborn as this position appears, unexpected discoveries have happened in science all through its history. In the early 21st century, for instance, it was found that the neutrino, in spite of its ghost-like properties, did indeed have mass, negligible as it is.

Nonetheless, they were looking for something the mathematics told them didn't exist, yet they looked anyway. From the perspective of their time in the 26th century, this zone was fossilized, dead, but now, here, it was alive and possessed of motion. But it was motion that never changed; it was fossilized in the sense of unchanging. And reality, the one they were familiar with, simply didn't behave that way. Things changed, transformed into the next thing, even if that next thing was itself. It never occurred to them that orientation of time's direction was not contained in the matrix, but rather induced by its networks into the many fractal dimensions it generated. That would've been a leap undercutting, in one stroke, their whole rationale for being here. As a consequence of this significant oversight, doubt and anxiety crept in, draining the heady confidence that buoyed them when they first touched down, taking it apart piece by piece.

Therefore, the computer couldn't lock onto any particular orientation in space because there wasn't any particular orientation. And the temporal induction machine's attempt to produce inverted time elementals as specified by the computer failed as a non-sequitor. The computer had nothing to specify. Opposite to what?

In the short time they'd been there they found themselves entertainig thoughts of otherworldy interference as well. It was a distraction they could ill afford. And it wasn't only instrumentation failures all around that were troubling. They heard strange sounds like music and laughter and saw flashes of movement out of the corner of their eyes. They tried to convince themselves that it was only the random, ambient noise of virtual particles in the surrounding sea, resonating through the hull in the quantum space they occupied. However, to scientists of their caliber, unanticipated events of this type were alarming.

And something was causing the computer's genetic material to lose coherency, to become unmanageable. It wasn't happening all by itself. Nothing they knew in their vast storehouse of collective knowledge could explain it. Was it happening on the molecular level? The atomic? The quantum? The sub-quantum? They had no idea.

Finishing their conversation on that dismaying note, as Hessenbalm climbed laboriously into his bunk, he mumbled derisively, "Goddamn magic is what it is."

Roger sat in another room adjacent the hall. He faced a wall tapestry of flowers and strange geometric patterns. This one stayed still. Its background was burgandy. Behind him stood Regina and Melophile. Regina had explained to him that, as she said, they have only a magical perspective--in particular, theirs--on the minds of the people in the ship. The two who are in charge think words for which the witches find no equivalent. They've concentrated their energies on them. Having ascertained their purpose, they wish to know how they intend to do it. They've gathered that they seek forces unknown to them that they believe are embodied and encased in what they call the matrix of fractal dimensions, which Regina and Melophile interpret as referring to their inner space. A complete reversal in understanding of the nature of this matrix--anchor--and how it actually functions. This mistake is at the crux of the matter. And elementals are what they're calling the sacred beings of time essence. It's clear, in spite of other confusions, that their mission is to destabilize the anchor. Precisely how they intend to do that is lost in those unknown words.

"We need to find out, Roger," she said. "We need to see their thoughts through a human lens. To translate and interpret. Each and every individual type of creature perceives the world through the prism of his mind. The mind is thought, and thought constructs the outside world, arranges it by significance. We can access their ideas beneath those words, but they've been all a jumble. We have nothing to compare them to. If we could see them the way our mind interprets reality, we'd know what practical things could be done."

"But, Regina," started Roger, "I'm no scientist. Their thoughts are as unknowable to me as they are to you, probably more so; in fact, most assuredly more so."

"No, Roger. What you can see, with our help, are ideas arranged in a certain pattern that falls naturally to your nature as a human. It's in your blood. Although overlaps are plentiful, it's quite different from ours. There is witch logic and there is human logic. You can show us images, and we will try to interpret."

"Ideas without words forming images on their own," he mumbled, "like iron filings in a magnetic field." He was lost in her world. Voluntarily wandering the streets of magicland.

"Relax, Roger. Relax and trust." She placed her hands on his temples once again, but this time, both she and her sister spoke, intoning a bizarre series of broken syllables. Roger stared at the tapestry, it drew him in and embraced him. Bodiless, he seemed to travel through a dark, long tunnel, but without any sense of movement. Suddenly, he found himself sitting in front of a console, a screen. Images and schematics covered it. He saw a hand wave in front of it, the picture changed. He looked around at other objects, instruments, set on a long table, in a room well-lit with overhead lights, the floor clean and hard white. He heard voices, english, but with emphasis in the wrong places. The body he seemed to be occupying said something unintelligible to another man sitting nearby. Roger grew agitated. It was all too strange; he felt he couldn't do it and tried to withdraw.

He heard Regina's voice in the distance, "Hold on, Roger, we're almost there." Tenuously reassured, he dug in and opened his mind. Let it all happen, he thought. What the hell.

He was falling, dropping through black space inhabited by oddly-shaped shards of geometric shapes, fluidly transforming into other shapes as he watched. Some drew towards others and fused, only to be separated again into even stranger shapes. He watched as several converged before him, collecting into an arrangement that had no sharp edges, vaguely forming a disc containing jagged segments of lines where shards joined. Abruptly, it dispersed into smaller components, to be replaced by yet another disc, almost the same size but varying by the fewer number of fragments. They seemed larger and yet more compact, as though smaller ones of the previous disc had merged.

He heard a voice, not the witches. Concentrating, the garbled words began to make sense. He heard one say something about the disruption of the bounding field. That they should try to engage the temporal disseminator despite the machine's malfunction. Any elementals were better than none. A full-scale survey may still reveal the progenitors. Another voice said they'd be wasting time working the glitchy machine unnecessarily. That the bounding field could be neutralized by an infusion of time elementals concentrated on the edge of the matrix, where it interfaced with ordinary spacetime. The first voice said they weren't yet able to build elementals precisely oriented, it was hit or miss. And even if they could, they didn't know the wavefunction of orientations of each network of the countless elementals on the boundary, the job of the computer, don't you remember?

A sharp pain jabbed at his head and chest; he crumpled to the floor. The witches were all over him, speaking spells and checking for vital signs. With help, he stood and was led back into the Great Hall of Mirrors where he plopped into his chair. Fralene had gone. Regina offered him wine, which he drank thirstily. She sat back in her chair and studied him, watching for symptoms of detachment and disorientation, and, of course, pain.

"Are you all right," Melophile inquired, not quite sounding like the nurse she wished to be. She was more afraid for him than concerned for his health.

"Yea," he mumbled into the table. "I'm all right. Just a little tired." He rubbed his hand over his head and asked, "What was that sharp jab?"

"Two minds were implanted in yours; it was not an easy fit." She almost laughed, but in deference to his ordeal, she suppresed it. Melophile, however, had no such compunctions. She snickered, she couldn't help it. "The images you saw, frameworks of ideas arranged according to their way of thinking. You now know what they plan to do or are doing. Think about it. I know you're drained somewhat and would like to rest, but we haven't the time. Drink some more wine, it's meant to help bring back memories."

Roger did so, then put the cup down softly, as though suddenly transfixed. He recalled the schematics on the screen. Ideas flooded into consciousness, he spewed them out. "They have a mechanism, a machine, that can produce time elementals. And another that can ascertain the," he paused for a moment, "orientations of the time direction of those of the anchor, in their premanifest form. As an," again a pause, "infinitesimal, a mathematical point devoid of properties, a virtual reality, an arrow of time without length buried in what they call the matrix. But neither of them is working right and they can't find the source of the problems."

He looked at her in earnest as if to ask if that was of any help. She stood behind him, a movement Roger didn't see in the making. She was sitting one moment and behind him the next. Placing her hands on his temples, she repeated the chant as before. Time moved slowly, her hands seemed to have a life of their own, feeling with their fingers for just the right placement. Seconds, minutes later, he didn't know, she dropped her hands and walked about, wandering, completely lost in thought. Her sister joined her, holding her hand. Abruptly, she stopped dead still and raised her head to the ceiling, awe spread over her face. She turned to Roger, sitting quite still, immersed in the moment.

As she approached him, smiling broadly, she said, "There is something going on in the background affecting both ship and crew. Something unanticipated. A presence with a mind of its own."

Hessenbalm finished off the last of their wine. The rest of the crew were nowhere to be found. He imagined they were probably in their separate quarters doing the same as he. They'd given up on the mechanism. They'd practically rebuilt it from spare parts, yet it would not produce time elementals to specs, any specs. And the computer's malfunctions were at the alarm level. What concerned them now was whether it would work well enough to get back home. They hated the idea of abandoning their most important project to date, but lives were at stake, their lives. They were disgusted and planned on raising hell about the equipment when they returned. If they ever did. Their superstitious leanings of late had grown problematic as well. Ordinarily, they'd surmise something unanticipated in the field strength of a known force. But now, despite scientific training and years of practical experience with time travel, they were beginning to believe in all manner of unnatural things. Forces beyond their understanding were manipulating events. The gods of Olympus were toying with them; angels sent from heaven; spirits of the dead angry at their intrusion.