long long time ago, Bob lived the life of a god. He'd been bound to Earth and responsible for rain to replenish the flora worldwide and especially the crops of the humans. But that wasn't what he wanted. He'd requested domination over the fires in the bowels of the Earth, volcanoes and rifts hundreds of miles long from which boiling lava poured, destroying cities, villages, forests, and people in an extravagant and spectacular display of godly rage and displeasure. Cleaning the slate and renurturing the planet in the process. But what was he assigned instead? Rain. From drizzle to monsoon downpour--his domain. Consequently, he was very bored and becoming more restless with each passing season.

long long time ago, Bob lived the life of a god. He'd been bound to Earth and responsible for rain to replenish the flora worldwide and especially the crops of the humans. But that wasn't what he wanted. He'd requested domination over the fires in the bowels of the Earth, volcanoes and rifts hundreds of miles long from which boiling lava poured, destroying cities, villages, forests, and people in an extravagant and spectacular display of godly rage and displeasure. Cleaning the slate and renurturing the planet in the process. But what was he assigned instead? Rain. From drizzle to monsoon downpour--his domain. Consequently, he was very bored and becoming more restless with each passing season.The humans made sacrifices depending on their local culture. Effigies in straw of what they imagined he looked like were burned, and elsewhere, goats and even virgins were ceremoniously killed on a slab of rock or marble--an altar--those that weren't thrown into a volcano. How that was supposed to help was a mystery to Bob. The god of earthly fires supplied decent soil after the fact, but helped not on a season-to-season basis. Why should he be appeased?

Droughts were his best time. Feeling unappreciated and resentful, he'd hold back the saving rain, torturing Earth, its creatures, and the people who depended on him for food and livelihood. It never occurred to Bob that he caused the droughts in the first place out of sheer laziness and a disdain for the responsibilities of his assignment. Other gods called him vindictive and mean-spirited and worse. Such accusations, however, were balm to his self-pitying soul. Attention, a little attention; that was all he wanted, some recognition. People were always going to appeal to his good nature, so what? He didn't care about them or their lame sacrifices, he wanted approval and praise from the other gods. However, that was not to be; in fact, the council of gods disapproved strongly of his behavior and one day called him to appear before them to resolve the issue.

The council consisted of five gods, Fred was the chief. Long before Bob's time, Fred had regulated the creation and rudimentary beginnings of Earth. He held mastery over the sun and its gravity and, during the great bombardment and formation of the planets, created Jupiter to protect Earth and its lifeforms from asteroids and comets. A few mishaps occurred, but the system worked well enough. And as it turned out, one of those unfortunate accidents set the stage for the emergence of humans. Not necessarily a good thing for the rest of the planet, however.

Sharlene, goddess of winter, was his consort. She had it in for Bob since the time he let her special garden high in the Himalayas go fallow from lack of water during one of his snit fits. It didn't look promising for Bob.

As hearings go, it didn't last long. Documented evidence of his sloppy work--allowing droughts to continue far too long in one area and monsoon-caused floods to occur in others--was plentiful. He shirked his duty while living the good life of debauchery and casual cruelties. "This can't go on," pronounced Fred, more than a little peeved. Bob slouched in his chair, ignoring the proceedings, engrossed by the play of sunlight on the crystal dais behind which the council sat. They talked among themselves, discussing the ins-and-outs, not even bothering to retire to chambers. After a few minutes, Fred spoke, "Bob, god of rain, the council has decided on a suitable punishment for your many willful and heinous acts." A pause, theatrical in part, separated them from Bob. He felt the disconnect and immediately sat up straight, hands folded in front of him on the marble table. But it was too late for displays of respect and deference. The hammer was coming down.

"We have decided, for the good of us all, that you must learn to appreciate the importance of your job description. Accordingly, you are to be stripped of your godly powers and sent to Earth as a human, to live among them, to learn from them, and to experience the meaning of rain firsthand."

Bob stood, knocking over his chair. "You can't do this," he pleaded. "I am a god, how can you force me to submit to the trials and tribulations of being human? I don't deserve it. Give me another chance. I'll do better, I promise."

The council members stood. Almondo, god of the rivers, sneered his ill will. Bob had been an uncooperative thorn in his side ever since he was appointed overseer of rain. He was quite pleased with Bob's punishment and, in fact, wished it was far worse. Bob didn't have a lot of friends anywhere, least of all on the council. He hadn't been playing well with others, now he was about to discover the consequences.

Fred spoke in a language Bob never heard before. When he finished, everything went black. Bob was aware of himself, but that was it; otherwise, he had no sensations, not of his body or of moving. As far as he was concerned, he remained in the council's courtroom. Time went by during which he felt a change come over him. Something lost, taken away, leaving him with what, he had no idea. However, he soon was to find out.

The stench nearly dropped him to his knees. Flies buzzed everywhere, crashing into his face, hitting his bare arms. Bodies of people lay strewn all around him, covered in blood, disfigured, limbs missing. His clothing was shabby and worn, his leather sandals muddied. Beyond the bodies a burnt field of straw undulated away towards a village near the horizon. An odd sensation grumbled in his stomach, and his mouth was parched. Bob had never felt this before. As a god, he had no need of sustenance; he lived off the energy latent in the void. But that was then; this is now. He couldn't waste any time feeling sorry for himself, he was in the middle of something horrendous and he better figure it out soon. He needed direction--find food and water.

He began to walk, another new experience; surprised that he knew how, he almost stumbled. Carefully, he navigated through the mass of dead to the dirt road adjacent. He gauged the village at 20 miles; how he could do that he didn't know. And whether or not he could walk that far, he'd have to find out. Banishment to humanity brought with it certain abilities he never before needed. Each was and would be an act of discovery, and with each he'd have to trust that he knew how.

It was hot, the sun beat down; he cursed Fred. Potholes scarred the road and the weight of wheels had gouged two deep tracks. On both sides were trees and thick brush. Not knowing what dangers may lie within, he walked down the middle. As he learned how to move his body, his sandals occasionally scuffed up small clouds of fine brown dust. His thirst intensified and his head throbbed as the heat and dry dirt in his nostrils worked his body. Twenty miles, he thought, and as he did, he began to try to figure out how long it would take. Like everything else so far, he never had to calculate distances and times; he willed to be somehwere and there he was.

Several variables were at play. First of all, does this road lead to the village or away from it? How straight is it? And if it does lead to the village and is fairly straight, how long will it take at my currrent speed? He had no idea about any of that. He was a stranger in an alien landscape and caught in the midst of some violent goings-on. With difficulty, he supressed the image of the dead as he walked away. Why was I there? he wondered. And why was I the only one alive?

In mid-shuffle he heard noise coming from around a curve in front. Relief at the prospect of water quickly transformed into serious misgivings. Remember the stinking dead bodies? he asked himself. He ran into the bush as quietly as he could and hid behind a fallen moss-covered tree and peered under a branch at the road. Men in uniforms holding long sticks of some kind walked down both sides of it. Between them were men and women tied to one another with ropes, maybe as many as a hundred, heading towards the pile of dead bodies. He knew instinctively that they would be killed, and they had to know that also. Why not fight? he thought. Why just let yourself be led down the road to your death? New sensations welled up. Anger, helplessness, outrage mingled and raced through his body, raw and unmitigated. He never considered death before; never had to; he was immortal. It'd held no significance. But now with its possibility and proof of its reality flung into his face, it meant everything. But he didn't understand why, he just knew it.

The uniforms prodded and kicked their prisoners. Bob grew angrier and wished for only one minute in possession of his god powers. They marched past with hardly a whimper of protest from the bedraggled mass of people soon to be killed. Bob decided to forgo the road and take his chances cutting across the thick jungle. He stumbled over underbrush; branches and twigs buried in years of leaves caught him up repeatedly, wearing down what little reserves he had left. Abruptly, he stopped to listen. A sound, continuous as it varied in pitch, came from ahead. He ventured forward, slowly, cautiously, pushing brush and tree limbs aside. The sound grew louder and more chilling until he broke through a hedge of bushes onto a narrow brook running speedily, cutting a meandering path. He fell to his knees and drank the cool water in stages. Revitalized, he rested on the sandy bank and stared up at the massive tall trees. Their canopy blocked out the sky; the heat from the road was well behind. He lay there, hungry but not in any foreseeable danger. In fact, he found solace and comfort here, even more so than when a god. No one knew where he was and no one pressured and nagged him to do his duty. He was beyond the reach of scrutiny and the constant criticism and disapproval he endured from those he deemed envious of his many gifts and talents. Now, here, next to this tiny stream, its innocent bubbling tranquilizing, in a jungle he knew nothing about, he felt free and protected. A temporary escape from the trauma of his current reality, he was to discover.

Putting the matter of the killing of all those people behind him--narcissism and a distinct lack of empathy having been among his more cherished characterisitcs--he was about to put a positive spin on his exile when a distant rumbling vibrated down his spine. Not even remotely aware of its source, but taking no chances, he closed his eyes and willed himself to be elsewhere, anywhere--walking his gardens back home--but the vibrations only intensified. He could hear tree limbs breaking and the violent scuffling of underbrush. Lying flat on the bank with high bushes on both sides of the narrow streamlet seemed like good cover. But, he thought, what if whatever is coming is coming this way? He listened intently as the cacophony drew closer, alarmed at the sound of heavy breathing. He tried to gauge the angle, but the crashing and labored grunts drowned out that possibility. A leaf floated by hurriedly as though it knew the proper recourse, he wished he were on it.

When the rapidly approaching whatever was practically on top of him, he stood to face it. Paralleling the brook, three massive horned behemoths raced by from left to right, unmindful or uncaring of his presence. Their grey bodies moved with a dexterity defying their size. And as quickly as they appeared, they were gone, engulfed by the jungle, the noise fading in pitch until silence returned, save for the birds and occasional loud discordant shrieking of some alien creatures.

He knelt again to drink, then dunked his head, pausing to listen to the muffled burbling. With adrenaline subsiding, the pang of hunger returned with renewed insistence. The positive spin he toyed with only moments ago vanished like the illusion it was, a hopeless and irrational pursuit. He'd been trying to fool himself, expecting the other gods to save him as they used to whenever he got into trouble. In fact, he'd always counted on it, believing they did it out of love and camaraderie. But now, he was on his own and he knew it. Food. Where?

He was about to take his first step when it suddenly dawned on him that the rampaging beasties who just flew by must be running from something far worse. Behind him lay the road of death. That leaves the way the panic-driven apparitions ran, whence they came, and straight ahead into the jungle. No choice there, he thought. Is this what destiny's all about? he mused as he stood waiting for his legs to move. Given alternatives, a person is reduced to taking the only rational path? Forced into it by conditions beyond his control? But surely if one is free to choose any possibility, that choice would be his destiny? But he was not free, he realized. In fact, it smelled to him like he was being channeled into a particular direction. Events were just too pat, too orchestrated, too coincidental.

He looked about for something to carry water in, but, except for large leaves, there was nothing. He drank his full and then determinedly strode into the dense forest, a stride that almost immediately turned into an arduous struggle. He fought for every meter, knowing his strength and stamina would not last much longer. Thirst crept up from the back of his throat and his stomach was tied in knots. He paused to catch his breath and wipe the sweat from his eyes. Barely visible splotches of pale blue sky lent a dim backdrop against which he saw something of color hanging from the branches of a strangely stunted and broad-leafed tree. When his eyes cleared and adjusted, he made out several, scattered at regular intervals, curving upward. Much shorter than the monsters surrounding them, they'd made a home for themselves on the hillock pushing up from the jungle floor.

He had no idea what they were, of course, but he knew fruit when he saw it. Forcing his way through the bordering brush, he climbed the knoll, the ground cover changing abruptly to long grass. Reddish-yellow and almost perfectly spherical, he picked one from a lower branch and without hesitation bit into it. Its succulent juices and sweet taste brought tears. He plucked a few and sat on the ground, his back against the smooth trunk of the tree. He glanced about, examining his find. The hill went on for a considerable distance before diving down on all sides into the unforgiving jungle.

He ate until he could eat no more, the juices quenching his thirst. Light was beginning to fade, night would soon be upon him. Reluctant to leave his orchard, he could in any event find no reason to do that. It felt safer and if need be, he could easily climb these trees, whereas the other type had their lower branches far too high to reach. Exhausted and dirty, but with a full belly, his body suddenly felt like lead. He pulled grass and stacked it into a bed, then as soon as he lay on it fell into a deep sleep.

He dreamed of floating with the clouds, his creations, his domain. Soft and fluffy, they buoyed him along, drifting ever so leisurely. Abruptly, his languor was interrupted by a distant muted rumbling. I didn't order that. How could this be? Who is doing it? How dare they? The raucous waves of heavy air grew louder and more discordant, a staccato of angry drumbeats. He stood on a cloud to peer in its direction. On the horizon coming towards him were three large grey shapes moving fast. When they got nearer and more distinct, he could see their massive hooves striking thick black clouds that appeared out of nowhere. They were heading right at him. He willed himself away but remained, helpless in the face of the onrushing stampede. He tried to bury himself in the cloud beneath him, but it resisted, refusing to grant entrance past its boundary. He was ostracized, on his own, lost.

He awoke with a start and sat up, sweat beading his forehead and wetting his back. Pushing against the tree, he scanned the darkness for moving silhouettes. Listening intently, he noticed that the whistles, cries, and screeches of night life appeared orchestrated, as though each creature took turn with occasional duets commanding center stage. He could detect nothing close by. He stayed that way, his back to the life-saving tree, relaxed yet alert until dawn began to creep up. Steamy mist rose from the upper branches of the great trees, filling the sky with whispy clouds. Fog settled on the woods below him, crawling up the hill like a melevolent beast. Being able to see was more of a relief than he would've imagined; night truly was terrifying. He was determined not to experience it again under these circumstances. The morning birds serenaded and raced about, oblivious of his presence, pecking at the fruit cores he'd strewn.

He awoke with a start and sat up, sweat beading his forehead and wetting his back. Pushing against the tree, he scanned the darkness for moving silhouettes. Listening intently, he noticed that the whistles, cries, and screeches of night life appeared orchestrated, as though each creature took turn with occasional duets commanding center stage. He could detect nothing close by. He stayed that way, his back to the life-saving tree, relaxed yet alert until dawn began to creep up. Steamy mist rose from the upper branches of the great trees, filling the sky with whispy clouds. Fog settled on the woods below him, crawling up the hill like a melevolent beast. Being able to see was more of a relief than he would've imagined; night truly was terrifying. He was determined not to experience it again under these circumstances. The morning birds serenaded and raced about, oblivious of his presence, pecking at the fruit cores he'd strewn.

He had enough of the heat the previous day to realize it was best to start trekking early. He removedd his shirt and filled it with fruit, slung it over his shoulder and with a painful good-bye to his protective tree, stomped ahead through the bountiful orchard, casually picking and eating as he went. The going was easy through the short grass under the lower limbs, but he knew it wouldn't last, so relished his freedom of movement. The sun peeked over the horizon, spreading its dominating influence over his world. Climbing down the other side of the mound he noticed a trailhead. How far it would go he had no idea, of course, but he gladly took it anyway. Did he have a choice? he thought again, his suspicions returning. It widened shortly to several feet where it met the thick jungle bush; the grass caught him about mid-calf. On either side the canopy enclosed it, just letting in enough light to see properly. Listening for the frantic pounding of hooves or the marching of men--two things he'd learned sofar to be wary of--he chewed a piece of fruit and silently gave thanks to Melissa, goddess of fertility.

The road meandered through the dense forest; the sun rose ever higher, sending out wave after wave of sweltering heat. The sweetness of the fruit, at first a pleasure, started to work against him, drying up his fluids where before the juice had replenished. Water is what he needed. Curving around a bend in the road he heard the faint sounds of what he wasn't sure. People. Were they coming his way? He stopped to strain his ears, the constant backdrop of jungle noises faded away. No, he concluded. Could it be coming from that village he saw? Could he have walked that far? And in the right direction?

He cocked his head at the sound of a squeeky wheel. His first impulse was to run into the bush and hide as before, but he let it pass and held his ground. He stood in the middle of the road, bare-chested in dirty pants and sandals with a shirt of strange fruit slung over his shoulder. His face was probably dirty as well; he didn't know and didn't care. The squeeking increased in steps until a boy pulling a low cart turned the corner. He froze at the sight of Bob who smiled as he lowered his bag to the ground. Language. What language do I know? I haven't tried that yet. He began to explain himself and his predicament, especially his need for water, and was amazed at the sounds that came out of his mouth. The boy understood and smiled back, offering Bob a skin-full of water pulled from the cart. While Bob drank greedily, pausing to catch his breath after each long gulp, the boy told him he was off to the orchard to pick fruit for the village, a half-mile or so behind him. Bob returned the water, thanked him genuinely, handed him a piece of fruit, and passed on towards the village.

Right about this time one would expect Bob to be sideswiped by fate, knocked off balance, rendered suddenly helpless by the irony and vicissitudes of events. Another test of his resolve and will to survive. But no.

As he came closer to the village, the road widened, its sides manicured and grass cut low. Trees thinned out leaving space for straw-thatched huts on sticks. The village itself was scattered over two hillocks, and the road he walked the one and only. In the center of town several people were busy buying and selling goods, stalls lined both sides. Bob had never had to pay for anything, although he was aware from overseeing rain how much money could be exchanged because of him. But, if that was the case, he was out of luck. He saw a man reach into a pocket and instinctively followed suit. To his amazement, he pulled out a wad of folding cash. He had a hunch it was country-specific, and not knowing where on Earth he was, he had to just go for it. But he was in no mood to be denied. He'd had his full of fruit, knots formed in his somach. He wanted cooked meat and that was that.

Entering the marketplace people noticed him. How could they not? Several stopped to gander, eyes blank. Bob recognized that he was a stranger who'd just walked in from the jungle, and looking the way he did, couldn't expect less. He only hoped they didn't turn hostile as he was well aware humans tended to do for the most inexplicable reasons. He ignored the onlookers and strode to where food appeared to be cooking, steam rose above the stall. If they were going to kill him, he thought, it was going to be on a full stomach of something other than fruit.

Three backless wicker stools lined the front of it. He inspected pots simmering various things he knew not over a wood fire. Instinctively, he requested that and that--he pointed. With smiles the road chef quickly put together a bowl of rice over which he poured strips of browned meat and gravy. Bob paid him what he asked as though he'd been doing it all his life. He could see that he'd not been abandoned completely without resources. Fred and the others had fashioned this human shape, but also the means to interact with the populace. Had he been dropped elsewhere, he's sure the outcome would've been the same. At least, so far. He knew from vast personal experience how mischievous gods can be.

He sat and relished his first meal in exile. He couldn't remember when he'd tasted anything so delicious. All the hundreds of feasts and banquets he attended, never actually tasting the flavor and feeling the texture and smelling the aroma of the food so arduously prepared by the souls of those deemed worthy to live with the gods. Would he ever be that selfish and unappreciative again?

People around him stopped their stares. It was a marketplace, after all, one didn't interfere with strangers. Villages nearby often came to buy. It was his attire, or lack thereof. He finished eating, paid for a skin-full of water, then, to free up the chair, moseyed over to a bench braced against the wall of a nearby hut and sat to rest and digest, content for the moment. He took in the crowd, trying to gauge how to behave and to ascertain some idea where he might be on the planet. He could ask, but wouldn't that be suspicious? The money offered no clue, the name on it was meaningless. So if he asked where he was, he would be told that name, not what part of the world it was in. Bob had never cared about names of countries, he had no reason to learn them. Names change but the land-shapes remain the same for millions of years.

His area of expertise was weather, climate, winds, ocean currrents, heat, time of year, slant of sun, stuff like that. He understood how it all worked--the hydrologic cycle--how the many parts interacted interdependently as a whole system, and how each whole nested within larger ones. He understood the nonlinearity of it, how the chaos of turbulence, after passing a critical threshold of energy, resolved into a storm. He knew this and more and yet never applied it fully to help keep Earth and all its inhabitants in balance. Self-indulgence is a demanding mistress.

Was this the intention of his banishment? he mused. Or was this only the prologue to far deeper revelations? He thought to lie down on the bench, shaded under a short but leafy tree, its soft thick straw looked very inviting. However, he didn't want to wake at night with nowhere to go, even if the people whose house this was would let him sleep there. Maybe if he told them he was the god of rain, they'd be more than happy to offer him every convenience and extend every courtesy. Right. More than likely they'd drive him from the village with a barrage of his own fruit, blasphemous madmen are generally not received well.

An old woman came out of the hut, she'd seen him through a window. She asked if he was all right, he looked a bit tattered. He smiled and told her exactly what happened, except for the part where he magically appeared in the middle of a bunch of dead people. He said he was taking a short cut he'd been told about, mentioning the orchard as a landmark and that it was farther than it seemed, but he didn't say where to, not having any idea, of course. They chit-chatted and Bob got the lay of the land somewhat by listening to her complain about the towns and villages in the surrounding area. The roads were in disrepair and it was up to the locals to maintain them, and so forth. She welcomed someone to talk to, and Bob welcomed the opportunity. She mentioned the name of the closest large town, a name he forgot as soon as she said it, to which he stated as his destination. Her sympathy poured out; Bob didn't quite know how to take that. She went back into her hut and returned with a shirt, worn but clean, and a large bowl of water for him to wash his face, placing it on the bench beside him. When it stopped quivering, he looked into its still surface and for the first time saw how he appeared. At first he was stunned, then relieved. He looked like everyone else.

He had no way of knowing how far it was to this nearest town along the one and only road. She said a word that he understood as a measure of distance, but he was unable to translate it into any measurement he knew. With heartfelt thanks and an optimism and hopefullness that buoyed his spirit, though belied his situation, he ventured forth, fruit and a skin-full of water, a gift from the old lady, slung over his shoulder. He walked easy, constantly listening to the strange sounds of the forest, now considerably thinned out; he could see well into it. The air was warm but not as humid as the jungle border. Occasionally, he spotted more fruit trees and stopped to pick fresh ones; eating them more slowly than before. Everything was going wonderfully well, considering, which his suspicious side found unnerving. Perhaps they were waiting for his arrival in this town to push him into another direction? If, in fact, they were doing that. Too coincidental, he kept thinking. Of all the benches I could've sat on, I chose that one. Or did I?

He passed a boy herding goats and a man pulling a donkey laden with metal objects heading his way. Not having seen any other trails, he guessed they came from the village. The trip was otherwise uneventful, the weather luxurious; his human body enjoying the exercise, his muscles gaining strength with each mile. The road widened as he approached town, its edges furrowed to carry off excess water. Noise and clatter and the sounds of voices greeted him long before he saw any buildings. A broad high wicker gate of varying-sized branches marked the entrance. It was open and appeared as though it hadn't been closed for awhile; the jungle vines and weeds entwined it, securing every crack and crevice.

When he turned the final bend he was suddenly confronted by a large crowd milling about in an expansive open space; at its center was a well where people were busy filling jugs and other containers. In groups of twos and threes they stood about discussing and arguing. Bob walked right passed them, ignoring questioning glances. The road narrowed between two-story homes of wood with glass windows. People sat outside, some working on domestic projects, most standing or sitting around talking with one another. No one paid him any mind. As he closed in on the hub of town he noticed an improvement in the quality of the homes, the elaborate architecture and well-kept gardens marked a higher class of residents than those on the outskirts. Here, traffic was heavy and no one sat outside chit-chatting. People passing paid him no heed, but he could tell it wasn't out of politeness or preoccupation, although there was plenty of that. He sensed trepidation, anxiety. He wasn't as finely dressed, by any means, but something else about him inspired discomfort. He had no idea what but decided it was better than having people agressively hostile and threatening.

The road ended at the town square, a hundred meters on a side surrounded by government buildings. Reddish-brown bricks arranged in a criss-cross motif covered the ground, a wide fountain topped by a statue of someone the pigeons seemed fond of provided the centerpiece. People sat around its concrete border, others strolled leisurely through knots of folks engaged in animated discussions. An outdoor cafe beckoned, he obeyed. The menu was readable, another fortuitous surprise. He wondered if he might be able to read and speak whatever was necessary; he put finding out on his to-do list. He ordered tea and a bowl of rice and fish, then surveyed the situation, studying interactions and looking for patterns of behavior. He had no idea what to do next, he had no plan or strategy. Most of his time he'd spent on surviving, but now, in the big city, or one of them, he had to come up with something.

He ate leisurely as one does when one has nowhere to go. Once again refreshed, he sipped tea while scanning for his next move. Down a side road visible from where he sat he saw a sign that read Hotel. Exhaustion leadened his body, the food only deepening his need for sleep. He remembered the previous night he slept but little, sitting up on guard till daybreak. He paid his bill and throwing his shirt of fruit and water-skin over a shoulder walked to the hotel, noticing the agitation in a few of the conversations as he went, people poking fingers at one another, their faces grimacing anger.

The spacious lobby had a cafe to one side; couches and chairs were plentiful in the main room. Most people stood about in tiny knots or sat engaged in avid conversation, a few relaxed alone, reading or simply taking in the ambience. A bar extended along the windows facing the street, doing a brisk business. At its center a decorative crystal chandelier hung, columns of marble facade braced the golden-brown domed ceiling embossed with geometric designs. Side-tables conveniently placed held lamps, ashtrays, and vases of fresh flowers; coffee tables held magazines and bowls of petals. Thick print rugs, worn in spots, covered the smooth wood floor in strategic places. Fragrant air contrasted sharply with the dank foul odor of the dusty streets.

The clerk at the desk raised his eyebrows as Bob approached and stared in disbelief at his request for a room. Bob didn't know quite what to do with this; he stepped back, wondering if he was doing the right thing. With other interactions for which he had no prior experience, he recognized that he'd been supplied by the council with inherent knowledge of customs and protocols which, up to now, had stood him in good stead. Most importantly, he understood the power of money. He searched for clues, perhaps he was at the wrong desk or the clerk didn't understand him. As he looked about, he couldn't help but notice that the others in the lobby were extremely well-dressed, and not only that, at least half looked distinctly different from him. The word foreigner popped into his head along with its meaning, an idea Bob had never considered before or had to. But who was the foreigner?

Bob tried again, enunciating as clearly as possible. The clerk leaned forward and told him point blank that he should consider another hotel, one farther down the road away from the square. He could tell the man was attempting to be respectful, difficult as it seemed. Bob got the drift. This was a high class place and his kind was not welcome. Doesn't he know I'm a god? roared Bob to himself. But suddenly, he burst out laughing at his image in the broad wall-mirror behind the clerk. Hair discheveled, shirt obviously of peasant origins, with what was now a filthy rag containing fruit and a water-skin over his shoulder. He shook his head and laughed as he turned to head for the door and out onto the busy brick-covered street.

He moved away from the noisy square, seeking refuge in the more prosaic section of town. Fatigue marked his pace. Not far, the bricks changed over to hard dirt. A little beyond he encountered a small park of well-trimmed grass, leafy trees, and benches scattered here and there. He walked to the center where there was a small fountain, its soft cascade soothing; found an unoccupied bench, dropped his satchel on the ground, and lay down on its curved-plank seat, using his arm for a pillow. Within moments he was fast asleep.

He dreamed of his garden, the main one with the elongated pond, lilacs surrounded it. The smooth flat-stoned walkways passed every kind of flower imaginable, and some that weren't. He lay on his divan; beside him a goblet of wine and bowl of cherries sat on a circular, glass table, its spindly gold legs formed a symmetry of curvature, stemming from the table, meeting at the center, and then blossoming out to form a three-prong stand. With the warm morning sun shining down, the gold and glass combined to reflect everchanging patterns and shades of light off the cool blue-green surface of the pond.

As he was taking a sip of wine, Melissa, goddess of fertility, shimmered her resplendent presence onto the divan on the other side of the table. She smiled that smile of hers--you know the one--and Bob beamed back. Gesturing, a tiny invisible bell rang that brought a servant with more wine and a goblet of gold dotted with precious stones for Melissa, sumptuous queen of inspiration. The day was shaping up pretty good. Maybe later he'd think about putting clothes on.

Pain coursed his body, starting at his ribs. He awoke to the sight of two men standing over him; they were wearing uniforms like the ones he saw on the road of death; in their hands were what he assumed were weapons. He understood that; how, he didn't know, instinct perhaps, part of the human makeup, an important part. One yanked him to a sitting position and in the process tore his gift shirt at the shoulder. The other stood on his bag of fruit. They demanded papers, proof of identity. Bob didn't know what they were talking about--the council must've left that out of the manual--but he was sure he didn't have it. Whatever it meant, not having one was not an option. He lied and said he lost his proof of identity when he fell into a stream in the jungle. They laughed. Grabbing him by both arms, they led him to a large van at the edge of the park and threw him in. Several others were already inside. The door slammed, leaving them in total darkness. He spoke to the void, asking what was going on. They all confessed to not having identity cards for various reasons, a few actually sounding legitimate.

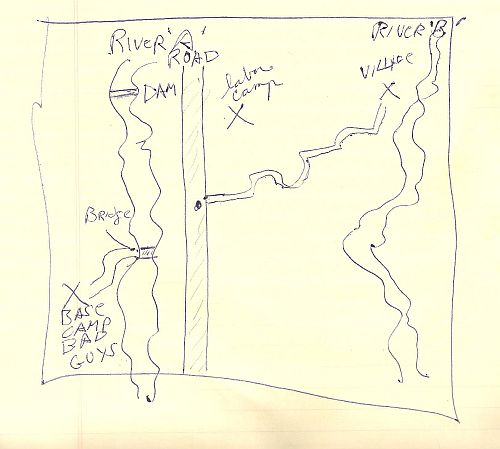

A quiet voice said he hoped they'd be taken to the local jail to be processed through the courts. If they could prove otherwise who they were by where they lived, all they would receive was a fine or minimal jail time, or both. Another disembodied voice, loud and gravelly, said he knew of a work project taking place further north building a dam. They needed labor and this is how they usually enlisted a workforce. Scouring the streets and parks looking for anyone in violation of law, any law. Either way, Bob knew he was screwed, another term that popped into his head unbidden.

The van sped off, blaring sirens as it went. Bob braced his back against the wall. He tried to think of what he could possibly do, but had nothing from which to draw, never having been arrested before. The shifting and hard smells of what could be anything sickened Bob; he feared he might vomit, but held on. Hunger once again gnawed at his stomach; hours must've passed. The hollow rumbling of the sheet-metal walls abruptly changed to bang and clatter as the van dropped without warning. One of his compatriots yelled above the din that they must be on the country road heading north. No one reacted to the news; Bob guessed they must've expected it. The rough and tumble ride continued unabated. Bob couldn't help it, he threw up, and so did others. The stench intensified with the miles, cooked by the suffocating heat. Bob lay on his side on the deck and discovered faint cool air oozing in from a crack under the doors. Numb from nausea and the unrelenting beating from the ruined road, he desperately tried to stay conscious.

He thought it couldn't get any worse; he was wrong.

The van slowed, eventually coming to a stop, its motor revving hot. Bob gasped, the air flow had ceased. Incoherent harsh voices vibrated through the walls, the metal adding its own peculiar and non-human timbre to the mix. The blackness now seemed comforting, he wanted to melt into it and tried in vain to will just that. Presently, they pulled away, driving slowly. The terrain was similar, but the speed made it relatively painless. Minutes passed. Yelling from nearby on the ground preceded an abrupt stop, the van screeched, the raucous engine died. The dark silence fell like a hammer of doom. The doors swung open, several uniformed men and one wearing a long skirt greeted them. They were ordered out where they were kicked to the ground. The man in the skirt inspected each. He waved at five, including Bob, and the last he gestured at dismissively; he was taken away. Rather insistently, the guards prodded them with their weapons, what Bob now realized must've been the long sticks carried by the other uniforms on the road of death.

They were herded to an outdoor enclosure bounded by a high, pole-fence topped by barb wire; they were shoved inside. Dozens of men milled about; blankets, small bowls, and piles of clothes were scattered here and there. Uniforms escorted them to the other side of the huge camp. There, a table held folded blankets and bowls with sticks for utensils; they each were given a set. The soldiers then simply walked away, leaving them to their own devices.

Bob peeled off from his companions who opted to stay together; ad hoc groupings formed that way in an atmosphere such as this. He stood still to scan his predicament while simultaneously searching his store of local human knowledge for any helpful advice; an actual solution, as in a course of action, proved too much to ask for. The expression up the creek broached the surface of his muddled mind. Deep shit was another one. How quaint, he mused. In light of his current circumstances, he needed no help inferring their meaning and significance.

It was late afternoon; men were coming and going. The ones reentering didn't look so good, thought Bob. He found a vacancy over by the far corner and lay down on his blanket, pleased beyond measure to be out of the van. He thought death had been near and wondered what would happen in that case. He hadn't given it serious thought until now; now seemed like an appropriate time.

He'd been stripped of his godly powers and his enduring spirit infused into and made one with the body of a man. Consequently, even though he maintained an objective view, he acted on human instincts and characteristics. His natural abilities and talents had yet to be fully plumbed and explored, put to the test. Thus far, he'd learned of his considerable stamina and will to survive, but not much more.

His former godly awareness encompassing the concentric shells of consciousnes from the godly realm down to that of human and the lowliest of lifeforms had been greatly curtailed. His perception was now constrained to a human universe, events were filtered through that medium. The mental constructs describing reality, though unfamiliar initially, he quickly processed and incorporated into a picture that was building in complexity with each new experience. He presumed the council had instilled not only knowledge, but also a proclivity for certain questions. Or perhaps not, perhaps given the basic tools it was supposed he'd be inspired to use them to formulate the right questions, difficult questions having to do with the nature of reality, human reality, by the desperateness of his situation.

He saw that his reactions were completely unpredictable and open-ended, thus far. In a flash of insight he understood that ordinary people were trained to react a certain way. Moreover, based on assumptions, people saw what they expected to see, intricate details were often overlooked. Their daily reality had a definite structure to it, inherited through generations, supported by language and imbued by culture. Through this, or by means of this, they went about their lives, believing what they'd been taught to be the way life is. He realized that his only freedom centered on controlling reactions by resisting imposition of the way life is. He had no intention of submitting to any fabricated reality. It was a mental attitude he was determined to engender and apply whenever necessary. He wanted to be able to step out of the moment and act in a most unpredictable manner; it was his only advantage. Other than that, he had no plan for getting out of the mess he was in. It was a confounding world which he was only beginning to flesh out.

Hunger and fatigue were all he knew, that and several bruises from the ride. He saw a line of people with bowls in hand queued up at the rear of the enclosure. Rising to his feet with the help of the fence, he shuffled over to it. The server plopped a dollop of white rice into it, nothing more. He looked inquisitively at the uniform with the scoop who told him none too pleasantly that his next meal would be tomorrow. Bob made it back to his blanket where he devoured the tasteless rice in three shovels of the sticks. He used a finger to wipe and lick the bowl which he then tossed aside. Depression wrestled with a growing anger. If only he possessed his godly powers for the briefest of time, he reflected, all these uniforms would suffer and the people here given a feast the likes of which would go down as legend.

He'd been there for less than an hour and already had decided to escape by any means. But first, he needed to know the lay of the land. His prison mates were familiar with the countryside, they knew where they were and what villages or cities were near. Gaining their confidence became paramount if he wished to avoid another pell-mell hike through the jungle, slogging along in what he imagined, at any rate, was straight ahead. It's easy to get turned around in a jungle or forest, especially when the canopy shields the sun. Besides, straight ahead may be the worse way to go.

Dinner time over, the prisoners lay down in the open. This high up in the hills, the night would be chillier than last, thought Bob. The sun dipped below the distant mountain peaks, darkness descended rapidly. He wrapped himself in his blanket, a luxury compared to the previous night, and scoured his mind for a plan, but he had little to base one on. His experience with vehicles had not been encouraging; he wondered if he'd been gifted with the knowledge to drive one. That would be a plus. He would have to wait until he knew more about what was going on, to get outside the encampment.

He stared at the stars, their brilliance almost painful. The galaxy stretched across the sky in all its glorious milkiness. He'd never seen it from this perspective before. When he was amongst them he'd taken their appearance for granted; not now, however. The contrast with total darkness framed them in a way that conjured images and inspired curiosity, a desire to understand their natures.

His dreams were wracked with bits and pieces of nightmarish encounters with demons and hostile beasts. He tossed and turned. With his godly powers, he vanquished them all, but it'd been stressful. There was no lolling about in the sun with Melissa, no pleasant fragrances from his gardens, no wine to forget the responsibilites of his office. A bad feeling crept into his psyche; recent events made their presence known. In his dream state, he thought again of death. What would happen if he let himself be killed? Was that a secret door out of this hellhole? Were the other gods watching, betting on whether or not he'd figure it out?

He awoke with a jab of pain, a guard stood over him. Hunger weakened his response. Prisoners were being rounded up, he along with them, and marched out at a brisk pace. The damp air chilled his bones, but he found it invigorating nonetheless. Some strength returned as he strove to keep up; he saw how others were beaten who lagged behind. A half-mile or so along the bank of a stream he came to where the dam was under construction. Trees cut down were trimmed and bucked before placement in the fast-moving water. A bridge ran across and from it short logs were lowered with ropes to workmen on another bridge near the stream's surface. These were dropped into position and braced by others at a 45 degree angle. Then the horizontal logs were knotched to one another and dropped behind the braces, upstream. Large rocks were deposited at the base of the braces in a hit or miss fashion. The whole operation looked dangerous as hell to Bob, unfamiliar as he was with actual work.

He watched in fasination at the skill and deftness of those at the business end, leading the inexperienced crews with orders and directions. His reverie was interrupted by a uniform shoving him forward to a pile of rocks. Along with several others, he was ordered to move them to the opposite bank, across the lower bridge, maneuvering around those positioning logs, to be handed to those standing at the edge of the stream, braced against the flow. The makeshift bridge was extremely narrow. Because of their weight, he had to use both hands to carry them, and so couldn't use the rope handhold to maintain balance. After his first crossing, he was exhausted; yet, somehow, he managed to plod on.

His mind was elsewhere, his body acted independently of thought. He wondered if the others were experiencing this ordeal in the same way. Their eyes looked dead to him. They were used to such labor, he thought. Somehow they found reserves to go on, day after day, forcing themselves to put one step in front of the other. A life thrust upon them, toiling under fear of death. Nothing could be done about it, it was their lot.

At mid-day he caught a break and lay down in the grass near the forest edge, gazing at the bright blue sky, savoring the warm mountain air, feeling aches in unfamiliar muscles. Guards were everywhere, there was no hope of escape into the jungle. He recalled his fight through it and mused that maybe escape into it wouldn't be much of one. He sat up to take in the surrounds, watching the workers and especially how the guards interacted with one another. Most seemed disgruntled with their assignment as though simply standing around with weapons was burdensome. Some joked, making the most of it. Generally, Bob deduced, they appeared less than alert, arrogant, their command of the situation a certainty, and uncaring of the welfare of the laborers; in fact, laughing and then getting annoyed when someone was injured. How long was he expected to do this? he wondered. And what would happen when his services were no longer required?

As a guard gestured for him to get back to work, a commotion downstream drew the guard's attention. Staccato gunfire ripped the quiet, birds squawked and chittered as they fled the trees. Uniforms shouted questions and then ran in that direction, leaving him and his cohorts unattended. With little hesitation, they headed into the jungle. Bob was tempted to follow but something held him. He wanted to know who was attacking. If they were successful, maybe he'd be safer with them than crashing through the dense unforgiving woods. The dam builders dropped what they were doing and scrambled across the bridges to the opposite side, not stopping when they hit the jungle's edge. Bob chose to stand his ground, alone; the uniforms were around the bend out of sight. Safety led away from the shooting, even he knew this, but he also felt an overriding sense of security being on his own. He could only guess that it was his nature now, or perhaps it was a holdover from his days of living by his own rules. Either way, he'd already learned to listen to his human instincts, gut feelings that demanded attention; if, indeed, the source was actually human. He retired to the treeline where he hid to watch.

Gunfire and angry shouts intensified, coming closer. He lay in the high grass and covered himself with leaves and branches, the pungent odor of molding underbrush filled his nostrils. Three soldiers ran in his direction; he held his breath, wishing to be invisible. As one, they fell under heavy fire. The attackers swarmed towards the dam; they were dressed in regular clothing but carried weapons similar to those of the guards. Bob thought to stand and wave his arms, yelling that he was a prisoner, but feared they might react out of caution and gun him down.

Abruptly, quiet filled the air. Around the bend a woman approached. The others spoke to her with deference, reporting all clear. She told them to collect weapons and ammunition. They quickly withdrew around the bend, leaving her alone to examine the partially-finished dam. He took a chance and stood, one foot ready to run. With arms high, he stepped out from his hiding place and walked slowly towards the woman. A twig cracked underfoot, she swiftly spun, weapon raised, and shouted for him to stop. He obeyed, keeping his arms up. He explained his situation as well as he understood it, the kidnapping at the park, the sickening ride, the bowl of rice, hoping she and her men were here to free them. She lowered her weapon and waved him forward. Relief coursed through his body as he shuffled towards her.

She asked his name and tribe. He started to say Bob, a simple one-syllable sound, but was astounded at what came out of his mouth instead--Ramajani. What trick is this, he thought. Did his cover include other like surprises, beneficial as they may be? His physical appearance and language matched the locale, as did the money in his pocket, these and others he hadn't noticed were fortuitous and unexpected. He'd been banished from the godly realm, but had not been left entirely without recourse. For that he was grateful and did not feel completely abandoned because of it, someone was watching. This was a test, a lesson, a journey he must endure and learn from. He hoped. On the other hand, it could very well be nothing more than part of his severance package.

As he approached, she asked if he was from such-and-such a tribe. He had no idea what she meant, of course, but nodded agreement nevertheless. When he got up close he froze, gaping at her beauty; he couldn't help it. The contrast of rough clothing--tight leather leggings, shirt open at the neck revealing taut, glistening skin, calf-high boots--hair braided into one thick luxurious black cord hanging halfway down her back, and the deadly weapon in her strong supple hands struck a chord in Bob he'd never known before, in spite of all the goddesses he'd been familiar with over the eons. The sight and sound of the turbulent stream behind her lent a vigorous energy and sultry wildness to her strong features and fiery eyes. He strove for objectivity, it was his way of gaining control of a situation, but it was useless. Rationality had nothing to do with here and now; emotions stirred, strong emotions. She introduced herself as Nalina, commander of her group from the so-and-so tribe. To Bob, the tribal names held no meaning, but thinking it important in a life-saving way to know who the friendlies were, made a note of them anyway.

She glanced once more at the dam, then began walking down the bank; Bob followed like a puppy, wishing only to be near. When they turned the bend he blanched at the sight. Bodies lay strewn everywhere, a few were hung-up on rocks in the stream. Men were tearing down the fence of the enclosure, the barracks of the uniforms burned hotly, a van lay on its side in the stream, its engine steaming vapor. He hoped it was the one that brought him here. Former prisoners sat in the grass eating food given to them by their rescuers. Bob hurried towards them, hunger eating a hole in his stomach. He was handed something reddish-brown that he didn't hesitate to stuff into his mouth. He relished its rich meaty flavor, strength and clarity increased with each bite.

He sat cross-legged with the others, blending in. Trucks commandeered from the now dead guards lined up in single file on the wide bank. Bob counted about a hundred men and women among their saviours. They were each dressed in clothing of his or her own choosing, some wore bright pieces of cloth around their head and colorful shirts, not what one might expect from a force trying to seek camouflage in the jungle. It was a sign to Bob of something holding significance that nagged him but would not surface.

Nalina stood nearby with two men discussing whether or not to blow-up the dam. They decided because it was only half finished the coming monsoons would take it out. Why waste dynamite? He and his fellows were told to load up in the second and third open trucks. The rescuers packed the others. Nalina sat in the seat next to the driver in the lead truck. Bob wondered how they'd gotten there on foot. Through the jungle? Up the road? He couldn't guess. They drove by the main gate, two men lay dead beside the guardhouse, their throats cut.

He could see where they'd come now. The road ran beside the river and was indeed a deeply rutted mess of potholes. Why didn't they fix this instead of building a dam that didn't seem to serve any purpose? he wondered. The water would back up and flood the jungle killing vast areas of trees. What was the point? Cutting off and regulating waterflow downstream? Who would that affect? It had to do with control and power, he could smell that much; he was quite familiar with power plays.

About ten miles along they stopped. Bob cautiously poked his head over the cab thinking they'd run into uniforms coming the other way. But what he saw amazed him. The driver stretched his arm out the window; in his hand he held a black box half the size of his palm. He pressed a button and the short trees, maybe twenty feet high, and brush levered in like a gate. In fact, it was a gate. He could see that the ground was what was moving, the thin, tightly-grouped trees and foliage were tied down with wire and rested on a sheet or slab of something or other. They looked exactly the same as those on either side, fresh and alive. They must be periodically replaced, he thought, or maybe they weren't even real.

Behind it a side road cut into the jungle. Because of its narrowness, the canopy darkened the grassy path forcing them to turn their lights on. However, their speed didn't diminish; if anything, they drove faster. The reason became clear when they turned a bend; a steep incline lay before them. Through breaks in the overhanging branches he could see the snow-covered peaks of mountains. With each mile the air cooled ever so noticeably. Bob wished he'd had the foresight to grab his blanket, his thin shirt was not going to cut it. He hunkered down in close quarters with the others; strangely pleased that they too felt the cold.

At some point, the road flattened out, the trucks slowed. Horns honked up and down the line. He jumped to his feet. Off in the distance he saw thatched huts similar to those in the village he came through, then along the road, several wooden buildings sat amidst yellowish broad-leafed trees, their tops protectively shading them. People were rushing towards them with smiling faces, cheering. The trucks pulled onto a broad flat area where other vehicles were parked and came to a halt. Everybody piled out. As he watched from the truck, the two groups merged. Their hugs and kisses and slaps on the back puzzled him. Such joy and congratulations at the killing of the uniforms; they must be sorely hated, he thought.

He climbed out and sought Nalina. She was conversing with an older man dressed rather formally in colorful robes. She took his arm and together they walked towards a large house at the center of the row. He had no idea what to do. One of the fighters informed him that food could be obtained at the last building up the road. He decided to take things one step at a time. Food, of course, that had to be first. A full belly might trigger an idea or two. Another item was something warm to wear; the chill mountain air combined with the weariness of his body and hunger caused him to shiver uncontrolably in spasms. His arms and legs were cramping up, he felt awful. He needed a respite and decided he wasn't going anywhere soon, unless, of course, they forced him to.

As he shuffled along, an old woman hurried up to him. She carried a short coat of some animal hide with a fur lining and offered it to him, saying that she noticed his trembling. She looked remarkably like the woman in the village who'd given him his shirt. He thanked her profusely and continued on his way, pulling the jacket tight around him, relishing its soothing warmth and earthy smell. Walking past the house Nalina had entered, he tried in vain to catch a glimpse of her through the open windows. Another word popped into his head--smitten. During his godly reign, he'd never been smitten or anything close to it. Always he maintained his distance, enjoying the pleasures goddesses had to offer, but not letting anyone get under his skin. How can he feel thus? he asked himself, a trifle alarmed. And she a mere mortal. He reminded himself that now, he too was human, a mere mortal, and was experiencing this new world as such.

He sat at a long, communal table eating fish, rice and some greens. He went back to the kitchen area for seconds, they obliged cordially. A large pot of green tea sat on a metal stand at the center of the table, a candle under it kept it warm. The building, open on all sides, was enclosed by screens. Columns placed every several feet supported the slightly angled thatched roof. The room could hold dozens of people. The other ex-laborers sat about talking and enjoying the hospitality, happy to be free of the nightmare they just endured. Across from him three rather rough men discussed the proposition offered them. Bob easedropped. Joining the fighters of this enclave would ensure a steady round of food, and also would give them the opportunity to get back at the uniforms. They called them by some tribal name, but, except to note it for future reference, he didn't care. To him they were the enemy, evil and worthy of contempt and even death.

That's it, he realized. Join these fighters here in this safe haven and be close to Nalina. He had to laugh. He had no home, no clothing, and very little money. He was a nobody, a peasant, an insignificant being lost in a sea of insignificant beings in this land of strife and misery. The image of the pile of dead where he first entered this realm flashed in his mind. That and his recent ordeal, brief though it'd been, evoked an anger he'd seldom known as a god. Then, anger emanated from without, intertwined with the forces he controlled with which he identified as one; now, however, in this human form, it rose from within, visceral and focused. He surrendered to it, accepted it, sure that it would carry him through the dangers as a fighter. They made it personal, that was a mistake.

But he knew nothing of their weaponry. As god of rain, he had lightning bolts and storms at his disposal, and heavy dark ominous clouds to squelch the spirits of the nonbelievers. He had to learn. He asked those across from him who to talk to about joining up. They stared, incredulous, then one with a smirk on his face gave him the name of Nalina's officers. He recalled the two men she conferred with about blowing up the dam. He finished his tea and with a spring in his step, ignoring the pain of his muscles, left to find one of them. Again he passed by the house where Nalina had gone and felt a longing that ate at his insides. The men were gathered around a bonfire, drinking and talking amiably. He found one of the officers and approached. He offered to join their forces, acknowledging that he was inexperienced with their weapons but was willing and ready to learn. The officer looked him up and down, especially lingering at his worn sandles. Presently, he responded kindly that first he should get some decent boots and a clean pair of pants, ones with fewer holes. The others around him laughed good-naturedly. He led him away to a small hut some meters into the forest and invited him in. Furnishings included four bunks, a dresser, and one round table set off to a side. Except for the area covered by a small print rug in the middle, the floor was hard dirt, a stout pole stood at its center supporting the circular roof. Pillows rested on the rug for sitting, there were no chairs. The officer dropped a pair of boots at his feet and told him to try them on. He rummaged through a drawer and pulled out a pair of pants which he threw in Bob's direction. He scrutinized Bob, then told him he obviously needed rest and offered a bunk. With that, he left.

Gratefully, Bob removed his jacket and lay down, pulling a blanket over him. Overstressed and overtired, he stared at the ceiling, a network of rattan so tightly intertwined that no light shone through. The distant sounds of music and laughter wafted through the open doorway. He felt safe for the first time, he'd found a place to recoup. A chance event to be sure, or was it? Settling down, his body relaxing in stages, sleep finally drew him in, to which he willingly surrendered.

He dreamed he was inside a massive house, a castle perhaps. How he knew of its size is part of the mystery of dreamland. It was overstuffed with furniture and personal belongings, none of which he recognized. Things laid strewn about the floors; objects, statuettes and manuscipts fought for space on the jumbled shelves that ran from floor to ceiling. He walked from room to room and wing to wing, searching for his identity papers. He knew they were here somehwere. He became frantic, worried. No light shone in, no windows appeared anywhere. He had to find proof of his identity, and then he must leave. But how? No doors were visible. Surely there must be at least a front door, he thought. As he hurried along, tearing apart boxes and opening drawers, people began to appear, people he didn't know. They seemed to know him however and endeavored to attract his attention, to talk to him as he passed, but he gave them no heed. He was on an urgent mission.

New wings with a multitude of rooms off to their sides kept appearing as well. Disorder was everywhere and increased as he went; yet the people, their numbers growing, didn't seem to care. They simply walked around or over the disarray. Some items caught his attention and he stopped to examine them; they brought back memories from long, long ago. Memories of a life lived for its own sake, but now scattered and meaningless, discarded, unimportant. He continued to search, feverish, tripping over things on the rugs, climbing what looked like the same stairway over and over. More people showed up, detached, self-absorbed, only triflingly aware of his presence and completely indifferent to his purpose and obvious dire distress. No one offered help. Fear gripped his heart; amidst the turmoil of so much stuff and places for it to be, he felt hopeless. He'd never find it. Pandemonium reverberated throughout the monstrous dwelling intensifying his desperation and frazzling his resolve. He stopped moving in the middle of a particularly spacious room complete with wraparound balcony. People gaped down at him, some smiling, others with a mean look in their eyes. He spun, taking in the chaos; lightheaded by the effort, he felt he might swoon. People on the balcony cheered him on, but to what end?

Abruptly, he sat up, sweat dripped down his face and back even though the doorway and windows were open to the crisp night air. Breathing deeply, the dream still in his head, he shook to free himself of its suffocating hold. Images stretched, deformed, tore apart, then bled away, becoming mere streaks of color draining down a hole in space. He scanned the room, forcing himself into reality. In the dim moonlight he saw that the other bunks were occupied. He rose quietly to step outside. All was still, the bonfire a pile of smoldering cinders; three men sat tendering it, talking softly, passing a bottle around. The half-moon gave just enough light to see nearby huts nestled under trees. Candle light here and there flickered through open windows creating an otherworldly atmosphere of peace and serenity the likes of which he'd not experienced thus far. He expected to see sprites on the wing and tiny gnome-like creatures scurrying about. Relaxed, he returned to bed and wrapped the blanket around him. He had no more dreams that night, at least none he remembered.

A month of rigorous training for him and the other ex-laborers who elected to stay had sharpened his senses and tuned his body. Moreover, he discovered that he was an excellent marksman; the weapon of choice becoming quite comfortable in his hands. He could take it apart and put it back together in minutes. Hand-to-hand combat proved more difficult, but he was determined to master it as well, and to his delight learned that this body the gods had bestowed was more athletic and stronger than he anticipated. He'd alredy knew of its stamina. Occasionally, he came in contact with Nalina who he thought of as goddess of war. Each encounter left him stammering; he felt like a childish fool. When a god, he'd never known shyness or constraint by protocol. He spoke his mind and did as he pleased. Reflecting on this self-indulgent behavior from his human perspective, he had to acknowledge it had something to do with his banishment. Arrogance may have been his trademark, stupidity wasn't.

The ambience of the village worked to set his mind in a particular direction, fostering clarity and purpose and an incipient moral compass, something he was completely without previously. He'd been accepted and felt a sense of fellowship he never knew amongst the other gods. And his name--Ramajani--at first somewhat disconcerting to hear, with time and repetition the melodious way they spoke it pleased him. After a day's training exercise, he would stroll about, visiting those he'd become friends with, eating at their table, or wander the woods, stopping to enjoy the chirping, tweeting, and melodious songs of unseen birds and the howls and screeches of mysterious animals. He watched the children play, oblivious of the dangers and suffering out there in the world. Such innocence, he couldn't remember when he felt that.

At times when he wanted to think and reflect, he'd leave the village proper to sit on his favorite moss-covered boulder and immerse himself in the jagged mountains far to the west, the snow on their tops almost melted away, until the sun dropped behind. He never tired of watching the shades of yellow and orange transmute into vermillion and blood red, then blend together in a moving, liquid, spotted swirl. He had to hand it to Fred--good show.

Afterwards, the soft breeze on his face, lightly rustling his hair, twilight throwing drawn-out shadows behind every tree and rock, he'd amble back to the hut he shared with two others. He watched his own shadow as it shifted and undulated over the ground, a novelty he'd never seen before and a testament to his earthly existence. He was beginning to feel less a prisoner trapped in a mortal body and more like a human with human sensibilities and emotions. These were dream-like times; he knew it wouldn't last, couldn't. That much he understood.

Nalina's presence was like a force of nature for which he had no defense; it overwhelmed him and he willingly allowed it to. He savored it like fresh cool wine or the fragrant, morning air. Pride no longer mattered; he wished only to do her bidding, to be at her command, to inhabit her world. She would smile sweetly at his fluster, aware of its cause. The gulf between them however had not diminished; leastwise he believed it so.

One day, after a round of shooting practice, she sought him out. She told him she'd been informed by her officers that he was a natural fighter and had the best eye of anyone among the new recruits. She was going on a reconnaissance mission into the heart of enemy territory. The village council, with her advice, planned a major assault on their main base of operations in this sector, the hub of their influence from where they sent out raiding parties on surrounding villages, capturing slaves to do their work, killing those deemed unworthy. She meant to destroy it, an act she was sure would break their backs and turn the tide.

They sat outside his hut on wicker chairs he helped build, no small matter to him. She asked him how he was getting along; he told her of his enjoyment at being here, the friends he made, the boulder he favored for watching the sunset, and the many forest creatures he came to love. He was about to tell her of his feelings, but choked on the words. Intuitively, she got the message and turned to him with the most beautiful smile he'd ever seen. She took his hand and spoke his name; he thought he would die right there on the spot. She suggested they go for a walk in the woods, she knew a secret place where a tiny brook ran through flowering shrubs. He was beside himself with joy, giddy as a child. He tried to restrain it, fighting for some measure of self-possession, but it was hopeless.

In the month he'd spent living and training there, they would often cross paths and cordially exchange greetings; he, of course, being a new recruit and she the commander, his was more formal; although he couldn't help the twinkle in his eye. Now they were off together, just the two of them, walking to her secret place in the jungle, perhaps where she prepared herself before missions, or only to get away from it all. Bob saw this as a definite change in the weather; optimism fueled him.

As they walked, he noticed he was identifying with his immediate surroundings in a way that invigorated him, as though a film or boundary of separation had melted away, everything appeared more vivid and real. On the path, bounded by tiny white flowers bunched together and only a few inches tall, he could see the smallest detail of twigs and leaves, of every bump and groove and furrow, and of the myriad shapes of stones embedded in the brownish-green soil, their edges and smooth curves, unique to each, glistened where light touched them. The massive broad-leafed trees, moss growing on one side of the trunks and lichen hanging from branches like clothing or hair, drew him in with a soft embrace. The shafts of light filtering through the canopy lent a richness of color and texture and contrast of brightness and shade, and above, patches of deep blue sky poked through here and there proclaiming fair weather.

As they walked, he noticed he was identifying with his immediate surroundings in a way that invigorated him, as though a film or boundary of separation had melted away, everything appeared more vivid and real. On the path, bounded by tiny white flowers bunched together and only a few inches tall, he could see the smallest detail of twigs and leaves, of every bump and groove and furrow, and of the myriad shapes of stones embedded in the brownish-green soil, their edges and smooth curves, unique to each, glistened where light touched them. The massive broad-leafed trees, moss growing on one side of the trunks and lichen hanging from branches like clothing or hair, drew him in with a soft embrace. The shafts of light filtering through the canopy lent a richness of color and texture and contrast of brightness and shade, and above, patches of deep blue sky poked through here and there proclaiming fair weather.

The hidden brook reminded him of the one he stumbled across his first day on Earth. It also brought back memories of horrendous beasts thundering and crashing through the jungle, almost running him over. Alarmed momentarily, he quickly scanned the area. They sat in silence for a time, listening to the burbling over stones and smelling the sweetness of the bush. Her proximity electrified him, quickening his heartbeat. Consciously, he brought it under control, afraid she might hear its loud thumping.

She spoke of her home far to the east and her upbringing, attending school and games played with the other children in her village, remote and apparently safely removed from the strife in the lowlands. But this idyllic life came to an end one summer day when she was a teenager. Uniformed men in helicopters attacked her village. He'd not yet seen a helicopter, but surmised by her tale that it came from the sky. No one had any weapons, only machetes and knives. They were slaughterd, the healthy men taken away for a work project, the young women, herself included, brought to their encampment; all others, the old and the children, were killed and the homes burned. She stared forlornly at the streamlet and threw a twig into it. He now had a glimpse of the source of her passion and ruthlessness and tried to think of something to say to bring her back, but instead touched her hand.

Immediately, she raised her head and smiled. She asked of his life, where he came from and how he managed to be in the labor camp. Telling her he'd been an immortal god who dwelt in a timeless realm didn't seem appropriate. He lied and told her he came from the one and only village he knew, but the rest was true, or almost true, that one day, on a whim, he ventured into the town where he was taken into custody. He'd somehow lost his identity papers and was found sleeping on a bench in the park. He described the miserable ride to the labor camp, which now he could laugh at, temporal distance and present circumstance mitigating the memory. He told her it was his first day there when she and her force attacked and rescued him.

She asked if he had a woman waiting for him back in his home village; he nodded no and managed to appear somber by the admission. He overdid it; she mocked his affectation with feigned sympathy, pushing his shoulder. They laughed, a quite innocent laugh that filled his heart with elation. It was her turn; he waited but didn't press. Birds trilled intricate convoluted songs up and down the music spectrum; monkeys called and howled; insects buzzed and flew around them, inspecting, curious, then off again, busy as hell.

After a time, she told him this village raided their camp, killing all the soldiers. She and other women who had no home to return to were invited here. Those who'd been raped--she didn't say if she had--insisted on learning how to fight and so joined the ranks of the fighters here, swelling the numbers significantly and bringing a much needed balance. She trained hard and constantly, rising in leadership.

One rainy night she and a small force were reconning a command post in the midst of the jungle when things went horribly wrong. A government patrol came up behind, hiking along the path they'd used, surprising her unit, pinching them between the post and the patrol. The commander was killed and all hell broke loose, her people were on the verge of panic, losing track of one another in the heavy rain and thick bush. The handful of men and women looked to her; she gathered them and led all to safety, sneaking through the enemy's ragtag line and back home. She was smart, cunning, and resourceful, and because of that, her skill with weapons, and her understanding of tactics, she became the new commander. Most importantly, she cared and would not leave anyone behind. That was three years ago.

He wanted to ask if she was with someone; he'd seen her with men, soldiers, but hoped it was only friendships, comrades who fought and risked their lives together. But he feared the answer so took the coward's way out and didn't bring it up. He expected she might be with someone, but then, why this?

Bob threw a twig into the streamlet while they sat in silence enjoying each others company, the interlacing sounds of the forest, the perfect temperature, and the respite from the day-to-day of the village. His mind wandered to thoughts of his gardens, the complex arrangements of flowers and fruit-bearing trees, the marble trails carefully chosen for effect, weaving through and interconnecting the varying types of garden and meeting at the many ornamental stone fountains. They were well-ordered, perfect in symmetry and design, a quality which always afforded him a profound comfort; a sense of intent pervaded that world. Nothing like this uproarious wildness with its cacophony of noises and random activity. It took some getting used to, and when he had, he found its openendedness and brash refusal to submit to rules other than nature's strangely liberating. Its heart was spontaneity and its body a manifestation of the possible. Earth had a will of its own, he learned.